I have a serious problem. I’m an insane person. More colloquially, I’m a hardcore DFS addict. I want to say it all started with my first big GPP win, but that’s not true. I didn’t really get obsessed with DFS on the level I am today until a reader took my advice and won $15,000 in the DraftKings Millionaire Maker. Since then, I’ve spent nearly every waking moment thinking of different ways my readers and I can gain an edge playing DFS.

In this series, we’ve already looked at wide receivers whose efficiency and production especially vary by speed of opposing cornerback, by skill-level of opposing cornerback, and by height and weight of opposing cornerback. This should give us a significant edge when looking at wide receiver versus cornerback matchups on a weekly level. Today, I wanted to mix things up and look at quarterback efficiency based on coverage scheme, to exploit a similar inefficiency in DFS pricing.

First, I calculated how often specific offenses faced man or zone coverage on passing plays and how often specific defenses played in man or zone coverage on passing plays. You can find that here:

Frequency of Offenses/Defenses Playing/Facing Man or Zone Coverage in 2016: pic.twitter.com/n5OFoHYm2Z

— Scott Barrett (@ScottBarrettDFB) July 22, 2017

For this exercise, prevent defense, abnormal coverage types, and goal-line and red-zone coverages were stripped out of our data sample. Cover-0, Cover-1, and 2-Man defenses were labeled as man coverage. Cover-2, Cover-3, Cover-4, Cover-6, and 3-Seam defenses were labeled as zone coverage. Though, note, these are very broad buckets, and each time a quarterback faces one of these zone schemes, there can still be man coverage within that on a specific receiver. For a more in-depth explanation of each coverage-type, I highly recommend reading the introduction to Eliot Crist’s article here.

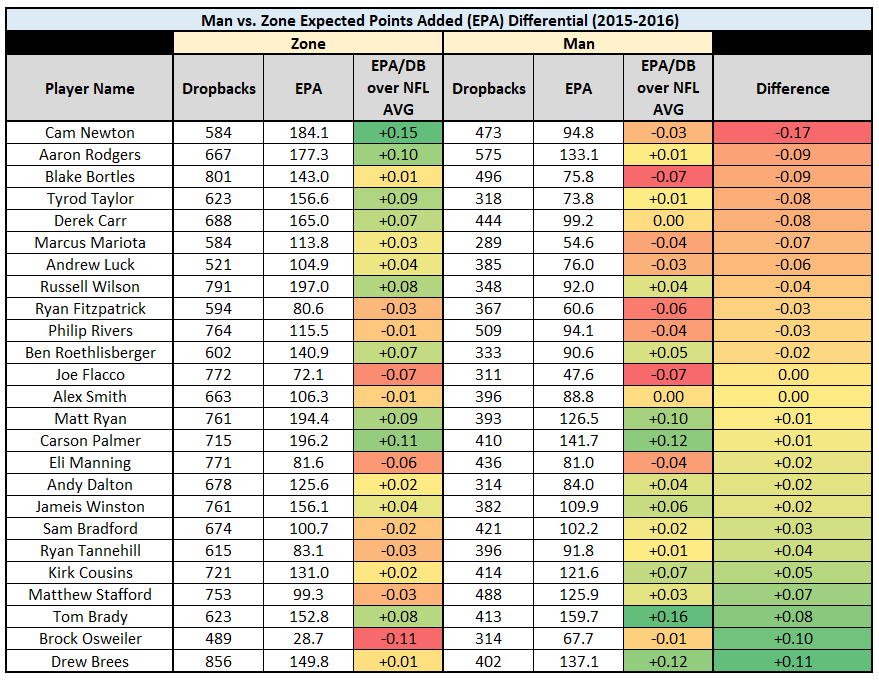

Next, I wanted to see which quarterbacks were most sensitive to a specific defensive scheme (man or zone coverage) over the past two seasons. Using our expected points model, in a similar manner to what Brian Burke has done at ESPN, I computed a QB's splits on man/zone coverage on a per dropback basis.

The quarterbacks at either end of the spectrum on the following chart were our most scheme-sensitive over the past two seasons:

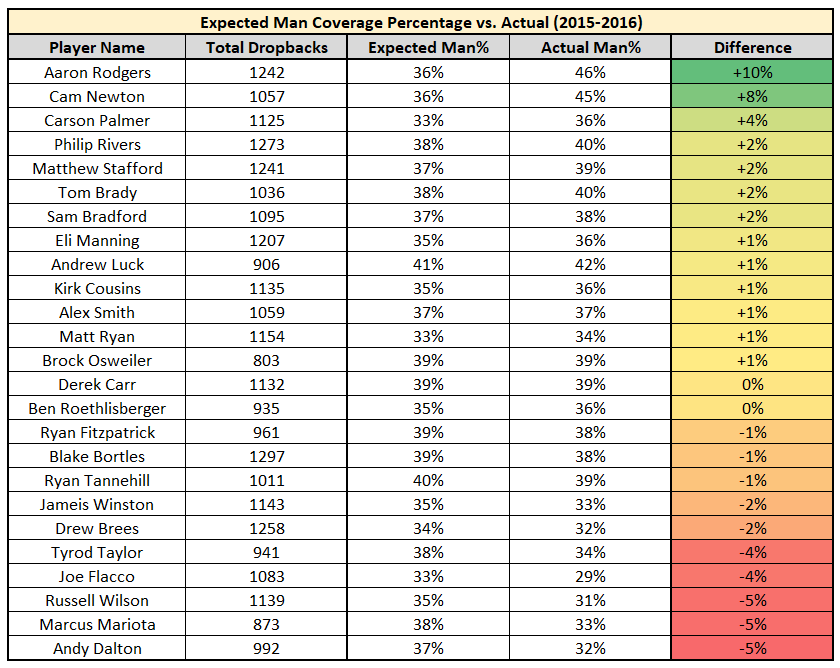

Finally, I wanted to look at how often defenses adjusted their scheme for a specific opposing quarterback. On a per-dropback basis, I built out an expected man coverage percentage based on season averages of opposing defenses, and compared that to the actual percentage a quarterback has faced over the past two seasons. Here’s what I found:

Analysis

Typically, when a quarterback struggles against man coverage, the implication is that the quarterback has poor wide receivers, is inaccurate, or doesn’t anticipate well (i.e., he has to “see” his receivers open). When a quarterback struggles against zone coverage, the implication is that they might have difficulties reading coverage, or that the quarterback is saddled with an uncreative offensive coordinator. Defenses are also far more blitz-heavy in man coverage. Over the past two seasons, teams blitzed on 48 percent of dropbacks in man coverage versus only 20 percent in zone coverage. Defenses with weaker cornerback talent also tend to play more zone coverage (as evidenced somewhat by our first chart).

After looking at all of the above charts, a few things immediately pop out. Here’s what was most intriguing to me:

Aaron Rodgers: Over the past two seasons, far more so than any other passer, opposing defenses made a point to switch to man coverage against Rodgers. The implication there is that they didn’t think Rodgers’ receivers could get open against man coverage. Based on Matt Harmon’s Reception Perception data (which measures a receiver’s ability to get open), at least last season, it appears as though they couldn’t. Rodgers was also significantly better against zone coverage over the past two seasons, ranking third-best in expected points added on a per-dropback basis, as opposed to only 14th-best against man coverage. Late last season, Mike Renner wrote about this phenomenon (defenses shifting to man coverage against Rodgers). Part of his reasoning for the uptick in production late in the season (Rodgers was our highest-graded passer from Weeks 10 through 17), was the emergence of Ty Montgomery. Renner wrote:

“Forcing defensive coordinators to decide whether to treat Montgomery as a wide receiver or a running back has allowed the Packers to get favorable matchups no matter which they choose. If it’s the former, then Green Bay gets a lighter box to run against, and if it’s the latter, then Montgomery will likely be matched up with a linebacker on a pass route.”

Cam Newton: Newton is easily the most scheme-dependent quarterback on our list. He led all quarterbacks in expected points added per dropback (over the league average) against zone coverage, but ranked eighth-worst (among 25 qualifying) against man coverage. Not only was he the best against zone coverage, but he was the best by a landslide. On a per-attempt basis, we see the same thing again. Over the past two seasons, Newton averages 8.8 yards per attempt against zone defenses (fourth-best), and 6.3 yards per attempt against man coverage (last). At a certain point, defenses seemed to become aware of this trend, playing in man coverage against Newton eight percent more than his expected total. Defenses opting to operate out of man coverage against him may also be to due his poor efficiency numbers when pressured; remember, man coverage is a more blitz-heavy defensive scheme. Over the past three seasons, among 25 qualifying passers, Newton's passer rating under pressure of 53.5 ranks third-worst (ahead of only Blake Bortles and Joe Flacco). Last season, Newton was blitzed on 40 percent of his dropbacks, while no other quarterback was blitzed more than 35 percent of the time.

Still, I’m mostly blaming Newton’s drastic splits on his receiving corps, and their inability to get open against man coverage. Carolina didn’t have a single wide receiver grade among the top-50 at the position last season, and as a whole, they ranked eighth-worst. Like with Montgomery’s significance to the Packers offense, perhaps the addition of first-round rookie Christian McCaffrey can help these splits. Since Newton entered the league in 2011, no team has targeted their running backs less frequently than the Panthers. McCaffrey (our highest-graded running back via the pass in 2015) in man-coverage, on an island against a linebacker, represents a significant mismatch in Carolina’s favor. Undoubtedly, however, I’d be eager to start Newton against especially zone-heavy defenses this season.

Marcus Mariota – Mariota was another one of our more scheme-sensitive quarterbacks over the past two seasons, especially struggling against man coverage. Given the wide receiver talent surrounding him over this span, that’s not very surprising. Since Mariota entered the league, a combination of Kendall Wright, Tajae Sharpe, Harry Douglas, Dorial Green-Beckham, Justin Hunter, and an over-the-hill Andre Johnson make up 77 percent of his passes aimed at wide receivers. After the additions of Corey Davis, Taywan Taylor, and Eric Decker this offseason, I’m guessing Mariota is more successful against man coverage this season.

Tyrod Taylor – Like with Mariota, Taylor was far less effective against man coverage than zone, though opposing defenses actually played zone coverage at a higher rate than expected against each of them. I’m not sure why this might be the case, but outside of Newton, we see a trend of mobile quarterbacks (Taylor, Mariota, and Russell Wilson) facing zone coverage at a higher rate than expected. Oddly, again, all three mobile quarterbacks (and Newton) are far better against zone coverage than man. Over the last two seasons, Taylor averages 9.3 yards per attempt against zone defenses (best), but only 7.1 yards per attempt against man coverage (fifth-worst). With Taylor too, it’s easy to explain away his man-scheme inefficiencies due to poor receiving talent. Despite Sammy Watkins grading out as our No. 12 wide receiver in 2015, the Bills have our fifth-worst-graded wide receiving corps over the past two seasons. Unfortunately, unlike Mariota, the Bills did little this offseason to inspire confidence that Taylor’s inefficiencies against man coverage might improve this season. Still his splits are impressive against zone coverage, so I’d be more likely to start him in weeks he might be facing a zone-heavy defense like when he faces Carolina, Cincinnati, or Tampa Bay this season.

Drew Brees – Shockingly, Brees was our second-most scheme-sensitive quarterback over the past two seasons, ranking third-best against man coverage and only 16th-best against zone. If it’s harder to beat man coverage with poor receiving talent, I suppose the reverse is true as well. The Saints had our second-highest-graded wide receiving corps in each of the past two seasons. This might help explain why Brees has been so good against man coverage over this stretch, although likely also because he’s been one of the most-accurate passers of the past decade. It is surprising he was only slightly above average against zone defenses, but I’m not particularly sure why. For whatever reason, opposing defenses barely adjusted their scheme for Brees over the past two seasons despite these splits, although the data suggests they should far more often next season.

Andrew Luck – I wanted to bring up Luck very briefly in anticipation of some sort of backlash from Indianapolis fans. You’ll note in our second chart that Luck looks only average against a combination of man and zone schemes (+0.01). That seemed somewhat surprising to me given his high ranking last season, when he graded out third-best among quarterbacks. His numbers were hurt by his injury-plagued 2015 season where he was our second-worst-graded quarterback among 37 qualifying. He was also at a detriment based on the fact that we’re looking at these numbers on a per-dropback basis, rather than per-pass attempt. Luck was constantly under pressure last season (44.4 percent of his dropbacks, the highest rate in the league), taking 41 sacks (second-most) behind a Colts offensive line that ranked last in pass-blocking efficiency.

Blake Bortles – Bortles appears much more efficient against zone coverage, but I’m taking this with a grain of salt. When teams take a significant lead, they often switch defensive scheme to more of a softer zone coverage. We already know Bortles has been a garbage-time hero over the past three seasons.

Brock Osweiler – Another surprise was that Osweiler was only slightly below average against man coverage, but also the worst quarterback in the league against zone coverage. The former point here is more of a surprise than the latter. Man coverage tends to be a more straight-forward defense, while zone coverage is more nuanced. Perhaps Osweiler was able to lean on his own raw physical talent or the strengths of his receivers against man coverage, but struggled to read defenses in zone coverage.

What does this mean for fantasy?

Unfortunately, I don’t think this data is very actionable, and especially not in season-long leagues. In general, I’d be much more likely to play Newton against a zone defense, but at the same time, due to offseason changes it’s hard to speculate whether or not this trend will persist for Newton, or when opposing defenses might adjust their scheme based on these splits. This is something I’ll likely spend more time with during the season. For DFS, I’ll be paying special attention to the most high-variance quarterbacks when facing defenses with the heaviest man or zone splits. For instance, Rodgers against zone-heavy defenses in the Bengals (Week 3), Steelers (Week 12), Buccaneers (Week 13), and Panthers (Week 15).

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.