When a quarterback’s stat line is listed at the end of a game or season, you’ll almost always see the same handful of statistics: completions, attempts, yards, touchdowns, interceptions. They’ve become so ingrained in our psyche that they shape almost our entire picture of who a quarterback is. One stat that rarely gets listed alongside the others is sacks. Many are quick to point to sacks as an offensive line stat, but a quarterback has far more control over their sack rate than they’re traditionally given credit for.

Just as a quarterback relies on his receivers to get open, an offensive line relies on its quarterback to get the ball out quickly. Both are symbiotic relationships that rely on responsibility to each party to operate at a high level. Depending on depth of drop, blitz package, and time to throw, there will be times where we won’t even charge sacks to offensive linemen. In fact, of the 1,118 sacks in the NFL a season ago, only 652 were charged to offensive linemen. That’s means we deemed only 58.3 percent of sacks as the fault of an offensive lineman. Sack avoidance is a group effort and doesn’t fall on one unit’s shoulders.

Not so coincidentally, avoiding sacks is also a huge part of running a successful offense. Last season, teams were only able to convert first downs on 16.01 percent of drives after a sack, according to SettingEdge’s Derrik Klassen. Calling them drive killers is an understatement. In 2016 though, no one avoided sacks at a better rate than the Oakland Raiders, and for that reason, they are the subject of this week’s Teaching Tape.

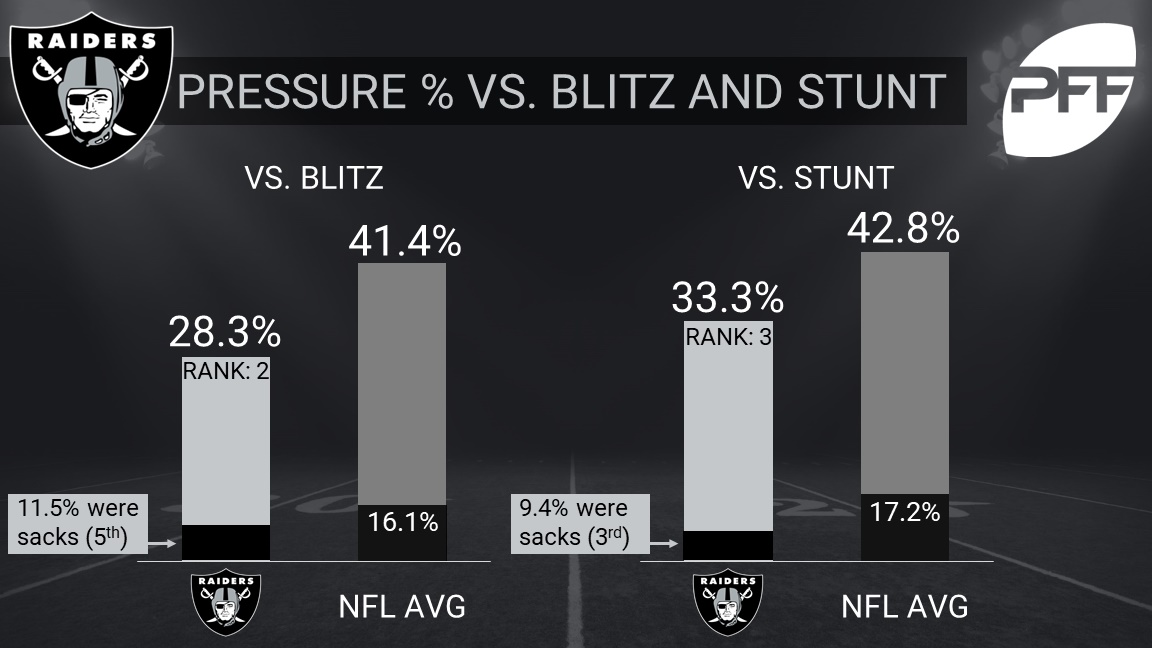

On 593 dropbacks a season ago, Derek Carr was sacked a grand total of 16 times, with only seven of those sacks being charged to the offensive line. And when it came to third downs, no one avoided pressure quite like the Raiders. They only allowed pressure on 30.2 percent of their third-down dropbacks and only yielded sacks on 2.6 percent, both tops in the NFL. The main reason for this was their proficiency in handling blitzes and stunts — two tactics employed generously on money downs — as shown below.

To put those numbers into perspective, four different teams yielded pressure at least 50 percent of the time versus the blitz while the same number surrendered sacks at least 10 percent of their dropbacks. That’s one in 10 dropbacks resulting in a sack versus one in every 30.7 for the Raiders. So how did they do it? As I said before, it was a group effort.

Oakland’s offensive line is proof that you don’t have to blow up the combine to be effective in pass protection. These aren’t a bunch of freaks like Tyron Smith who could mirror a squirrel in pass protection. No, the four-headed monster of left tackle Donald Penn, left guard Kelechi Osemele, center Rodney Hudson, and right guard Gabe Jackson get the job done with technique and some of the most powerfully deadening first punches in the NFL. Right tackle may have been an issue throughout last season, but it is much easier to scheme chips and slides when there is only one issue on the line and it’s on the edge.

From my description of the Raiders offensive linemen it should come as no surprise that they handled stunts as well as anyone in the NFL. There are two key elements when handling a stunt. The first is maintaining correct depth between adjacent linemen. The second is getting a healthy punch before passing off. On the play below, both of these pieces are present.

They might be the best team in the league at passing off stunts. Kelechi Osemele is out for blood every time he recognizes one pic.twitter.com/0MTVsCNzmB

— Mike Renner (@PFF_Mike) June 28, 2017

The Ravens run a tackle-tackle stunt as the Raiders are sliding right. As you can see, Osemele at left guard has no time for that. He makes sure the 1-tech can build no momentum looping around and then finishes him off. Jackson at right guard has to play it a little differently though because where the slide is going. He can’t follow the 3-tech inside because he knows he has to pick up the looper. This is where levels matter. Hudson at center is right on Jackson’s hip as Jackson gets that solid punch to pass off the defender. Many of the same elements that go into picking up a stunt are present when picking up a blitz. The one component that gains even more prominence is awareness. Sometimes protection calls won’t perfectly matchup with the blitz package. When that happens, one can’t simply sit idly by staring at a defender who isn’t rushing the passer. They have to look for work. The play below is a great example of that. Right tackle Austin Howard is eyeing Melvin Ingram before he drops. His eyes immediately turn back inside and he finds the defense tackle looping out for contain. Jackson’s eyes work back inside as well and he attacks the linebacker so ferociously that he’s forced to make a business decision. Both are made to look easy, but that’s not always the case.

They embody what it means to not be passive in pass pro. Watch LT Donald Penn and RG Gabe Jackson attack like they're the defenders pic.twitter.com/NjFfZbuGZO

— Mike Renner (@PFF_Mike) June 28, 2017

Once again though as you can see, Carr gets the ball out in rhythm and it weren’t for a horrific drop from Michael Crabtree they would have converted the first down. The Raiders quarterback had an average time to throw of 2.38 seconds, the ninth-fastest in the NFL last year. An offensive line can only be expected to hold up for so long (on a normal drop to seven yards that cutoff is a little under four seconds in our grading) and holding it beyond the framework of the play only invites more pressure.

All those factors go into making the league’s most effective offense at avoiding pressure and sacks in the NFL. Negative plays don’t show up as prominently on a stat sheet, but they have a big effect on offense nonetheless. With the exact same unit returning in 2017, look for the Raiders offense to once again be the class of the NFL at avoiding sacks.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.