Senior Analyst Mike Renner returns with his “Teaching Tape” series, a weekly feature in which he explains how and why the best in the NFL are successful at what they do. Renner's first Teaching Tape article of the 2017 offseason dives into the extreme patience and vision of Pittsburgh Steelers running back Le'Veon Bell.

When the book closed on the 2017 NFL Draft, 26 running backs had been selected over seven rounds. After each was picked, you’d hear about the prospect's size, 40-yard-dash time, and production. What you rarely, if ever, heard was how good their vision was. True, it’s difficult to assign a number to an intangible quality like vision, yet when it comes to NFL success, it may be the most important aspect in the evaluation. Former Browns and Colts RB Trent Richardson could shred arm tackles at an elite level, yet couldn’t find some holes right in front of him. Arian Foster, in contrast, was neither fast nor elusive, yet produced three straight 1,200-yard seasons with the Texans (2010–2012) because his vision was superb.

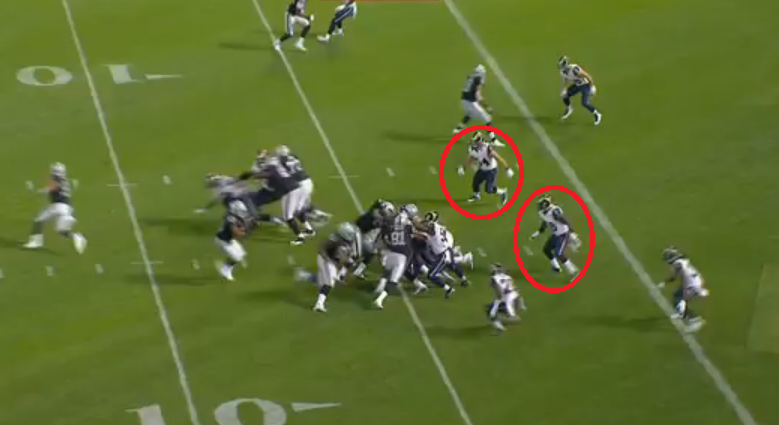

What gets even trickier when talking about vision is its scheme-specific nature. Lamar Miller looked like an elite running back executing a zone scheme in Miami, but an average one in a more varied scheme like that which Houston ran last year. To understand vision, one has to understand the reads running backs are asked to make and how blocks set up. One of the best examples of this comes from the aforementioned Richardson. For all his shortcomings, the infamous screenshot of him in preseason with the Raiders missing a supposedly wide open hole was not nearly the blunder it was made out to be. Most of you, I’m sure, have seen the picture below.

What that picture doesn’t tell you is that it’s a power run play, and there is a guard pulling from the backside to lead Richardson right through the hole. The angle you likely never saw below is far more telling.

On that play, cutting backside through the gaping hole would lead Richardson right into two unblocked linebackers, because the offensive linemen on the play set up to cut off those linebackers off the right tackle. For all of the examples of Richardson’s sub-par vision, this isn’t one I’d get too upset about.

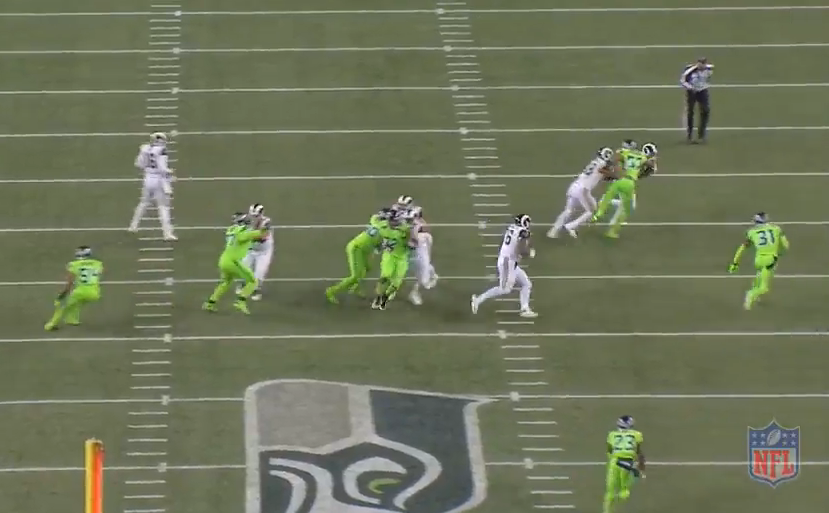

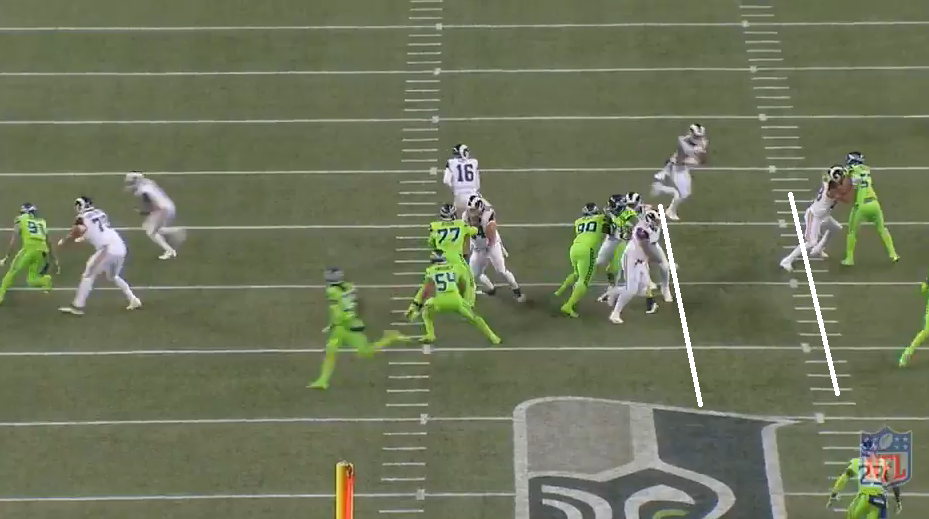

For an example of truly poor vision, we turn to Rams RB Todd Gurley’s nightmarish Week 15 game against the Seahawks. With 3:50 left in the second quarter, the Rams ran a little misdirection pitch play off of jet action. When Gurley catches the pitch, the blocking set up like so:

While there is some wide flow on the play, Gurley’s first read on the play is the leverage of his tight end on the edge. Lance Kendricks has Michael Morgan kicked out for a perfect lane inside. Gurley completely misreads it and goes against his own blocker’s leverage, resulting in a 6-yard loss.

An offensive line can only see what’s in front of it, making it imperative for running backs to do their part in setting up blocks, as well. No one personifies this more than Steelers RB Le’Veon Bell. He’s become famous for his ultra-patient style that sees him come to a near standstill at times behind the line of scrimmage. It’s an approach he can execute because of his exceptional burst, but also because the Steelers' run scheme affords him that time.

There are three core concepts that fuel the Steelers' running game: inside zone, power/counter, and blast runs. Inside zone is one of the most ubiquitous concepts in the NFL today, but the Steelers put their own spin on it. With it — and the other two concepts — the Steelers sustain their double-teams at the line of scrimmage as long as any line in the league. On the blast and inside zone plays, every interior player is doubled, while the edge players usually get single-blocked. They can afford to one-on-one block the edge because defenders there have the most to lose. If an edge player gets greedy and abandons contain, it will likely result in a far bigger gain than if a defensive tackle tries to be a playmaker.

The goal of this blocking style is two-fold. The first objective is to obviously move the line of scrimmage. The second is to make life difficult on the linebackers. In most one-gap defenses, linebackers are taught to attack downhill into their gap once they see the double-team in front of them so that the defensive lineman doesn’t get swallowed up. If a linebacker commits early against Bell, though, it simply gives him more time to find where the flaw is in the defense.

Take the play below against the Miami Dolphins. The linebackers play it perfectly, attacking and forcing the offensive linemen off the double-teams. Bell anticipates the flow, though, and slaloms against the grain until he finds the one gap the Dolphins didn’t have the numbers to defend.

— Mike Renner (@PFF_Mike) May 16, 2017

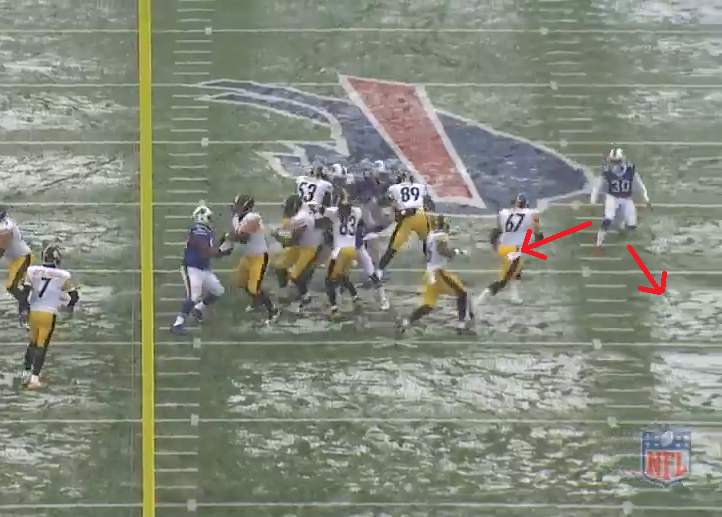

When the Steelers go with a lighter front, Bell gets even deadlier. In the play below from the classic Week 10 matchup with the Cowboys, the defense was screwed before the play even started. The Cowboys have six defenders in the box to cover a possibility of seven gaps with the offset fullback. All Bell had to do was find the one Dallas couldn’t cover.

Writing about Le'Veon Bell's patience. No RB makes DLmen pay more for peaking out of their gap pic.twitter.com/sZIvKy2r5i

— Mike Renner (@PFF_Mike) May 16, 2017

Bell’s initial read is the frontside B-gap. Dallas linebacker Sean Lee doesn’t bite on the split action and fills that, causing Bell’s eyes to track backside. Terrell McClain plays the double-team well and maintains the A-gap. The key then on the play is the backside 3-techninque, Maliek Collins. Anthony Hitchens is tasked with two-gapping the fullback, but Collins gets greedy, thinking Bell will follow his lead blocker. The rookie defensive tackle peeks far too soon, and because Bell was so slow to the line of scrimmage, he can get all the way to the gap Collins abandoned for a big gain.

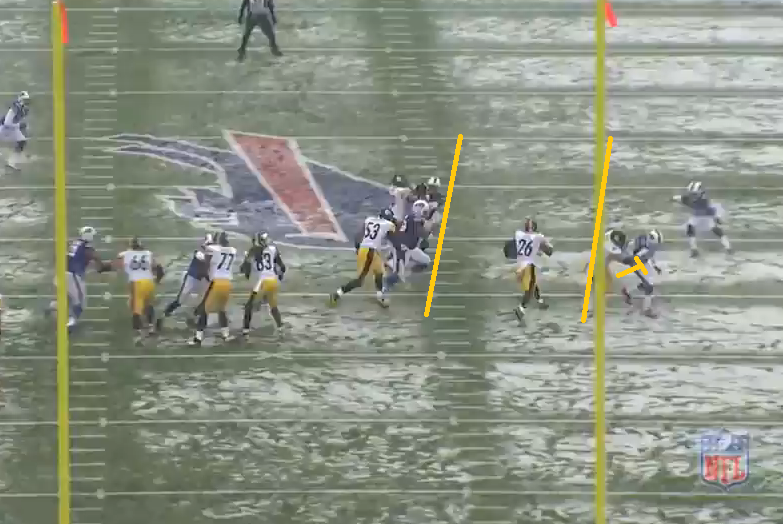

The final way in which Bell’s running style is so deadly is the way he stresses the leverage of blocks. As I touched on in the beginning of this article, backs can make the jobs of their offensive linemen easier by pressing one hole before darting into another, making the defender widen. This is especially effective when Bell is working out to the edge on counter/power. In the play below, the blocking has already set up in such a way that Bell has a lane to gain good yardage by cutting upfield.

He doesn’t get north-south immediately, though, just because there is space. Instead, Bell correctly stays on his course behind the pulling guard, making the safety dropping down into the box declare to the outside before heading upfield.

If Bell were to cut upfield at the point of the first screenshot rather than the second, he would have made the guard's block look much worse and given the safety a chance to make a play.

This is Bell’s genius. He’s an exception to the rule in many ways, as his extreme patience wouldn’t work without top-tier athleticism and the Steelers' complementary scheme. With those two things, though, he’s nearly unstoppable, and that’s why he provides the “Teaching Tape” for vision at the running back position.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.