[Editor’s note: This is the sixth installment in Senior Analyst Mike Renner’s “Teaching Tape” article series, which takes a look at the best positional units across the NFL.]

Work smarter not harder. It’s a cheesy self-help slogan I’m sure you’ve heard ad nauseam. It also happens to be the key to New England quarterback Tom Brady’s continued success. Whether it’s been a conscious or subconscious decision on his part in his advanced age, Brady has been trending toward shorter, quicker throws over the last five seasons.

| Year | Average Time Before Attempt | Average Depth of Target |

| 2011 | 2.47 | 8.6 |

| 2012 | 2.42 | 9.1 |

| 2013 | 2.39 | 8.9 |

| 2014 | 2.34 | 8.2 |

| 2015 | 2.26 | 8.3 |

Why do all the work – and take all the hits – when you have young talented playmakers who’ll do that for you? This is the Patriots offense in its current incarnation. Loaded with skill players that can create separation underneath, Brady is feeding them as quickly as he can and the offense is playing at as high a level as it has since 2007. If you want to install a quick passing game into your offense, New England is a no brainer to provide the Teaching Tape.

The Patriots hoarding of slot receivers has become a joke of sorts throughout the NFL, but when you look at the results, it’s Bill Belichick who’s laughing. On passes thrown within 2.2 seconds of the snap a year ago that weren’t screens (40.9 percent of attempts league-wide), Brady led all quarterbacks in completions (226), attempts (332), and yards (2,407 — first in the league by more than 500) while he was second in touchdowns (20) and only threw three picks. He did all that while still maintaining the seventh-best yards per attempt on those throws in the NFL (7.25). The statistics are mind-boggling.

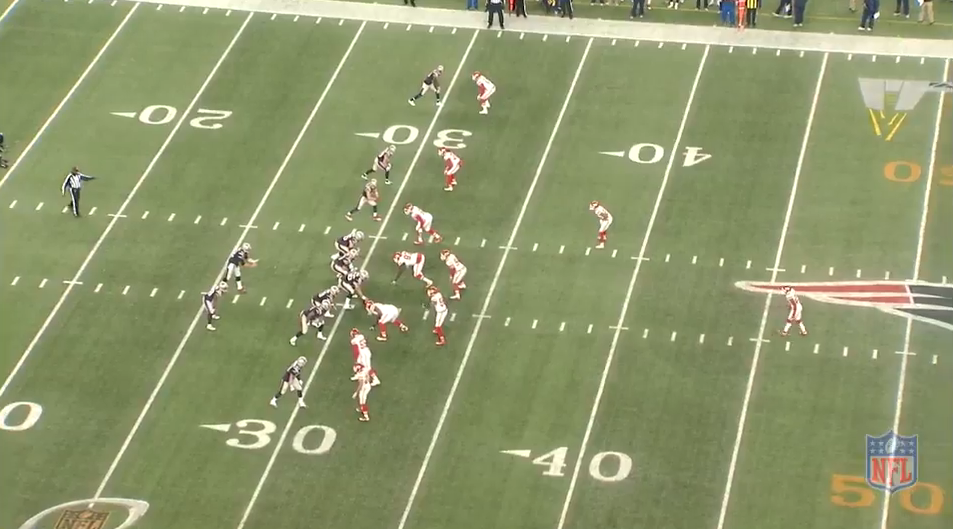

So how do they do it? By playing matchups. 2.2 seconds isn’t enough to scan the whole field and decipher the intricacies of the defensive scheme. Much of Brady’s decision-making comes from the pre-snap alignment of the defense. Once he receives the ball, Brady does little more than read the defenders in a small area of the field to be able to get rid of it so swiftly. Below is the setup of the first play to start the second half in the Pats’ playoff game against the Chiefs.

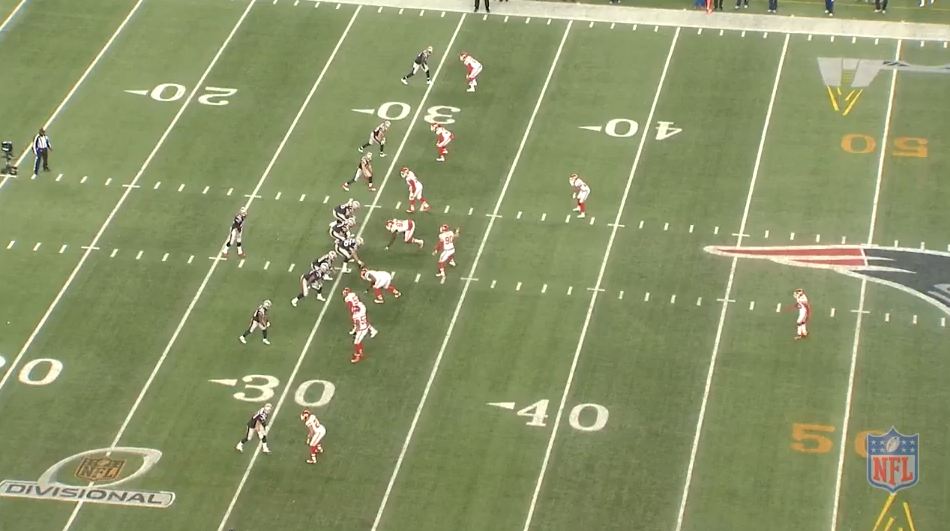

The press on the outside and head-up alignments elsewhere with a safety in the middle of the field strongly suggests man coverage (the Chiefs are also a very man-heavy team). Brady sees that the coverage has also isolated Rob Gronkowski on Tyvon Branch. Advantage: New England. Brady resets the formation into what we see below to capitalize on this mismatch.

Gronk splits out even wider while James White is moved from the backfield to the slot, taking linebacker Derrick Johnson with him. The Chiefs don’t audible out, so the Pats run one of the most widely used route concepts in the NFL today, the slant-flat. Gronk’s slant route is great versus man coverage. The flat route is not a man-beater, but it does the job of removing the linebacker from underneath the slant. If they were to run the same routes from their previous alignments, Johnson would have flashed right through the passing window when Brady wanted to throw and it wouldn’t have been nearly as clean a window. Instead the result is an easy 18-yard completion as Brady puts on a masterclass in quarterbacking.

Against man coverage finding favorable matchups is easy, but against zone it gets trickier as it’s less about the skill differential and more about formations. This is where scheming comes into play. Below is a crucial 3rd-and-4 in a two-minute drill against Houston, one of the top defenses in the league. New England has trips left, yet the Texans only have two defenders within 10 yards of the line of scrimmage in position to defend. It becomes little more than a version of basketball’s 3-on-2 fast break, where if they can space themselves correctly it should be an easy conversion.

That’s exactly what they do, as Danny Amendola runs a spot route from the outside to find a hole in the zone. Keshawn Martin runs a flat route. And Gronk is little more than interference as he heads straight upfield taking the outside corner with him. The Texans don’t bring the blitz and instead drop into cover-4, meaning only one defender is responsible for the flat on that side. The problem is two routes are run to the flat, flooding the zone. The result is that slot cornerback Kareem Jackson is caught in a bind through no fault of his own, and little effort is needed from Brady for the first down.

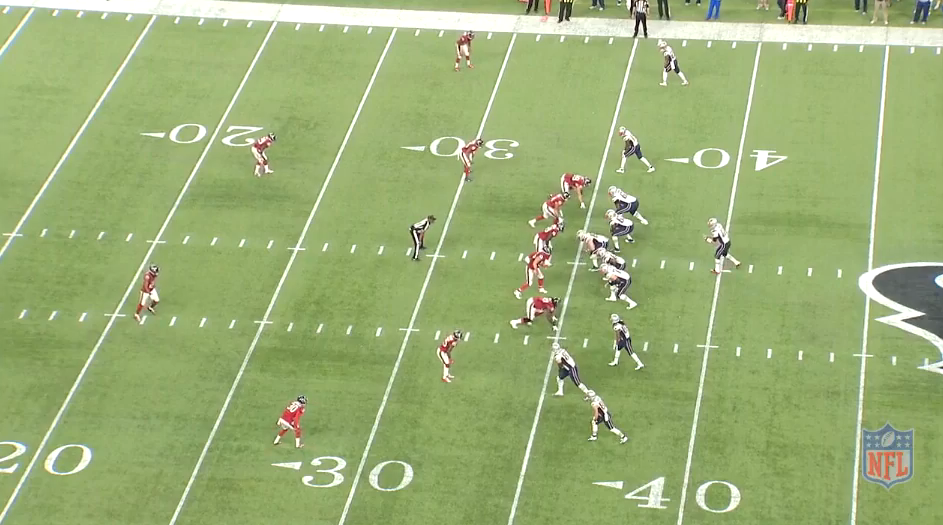

3-on-2 situations like that don’t happen often though, and sometimes favorable looks against zone have to be manufactured. This brings us to the deadliest and most underrated aspect of the Patriots offense — their use of pre-snap motion. Time after time, opposing defenses don’t adjust their coverages correctly to the motion and leave gaping holes in their zones. It doesn’t even take much digging to find blatant examples this. Take, oh, I don’t know, the Patriots first offensive snap of the season.

Rob Gronkowski lines up in the backfield before motioning out to the slot, and the Pittsburgh defense acts like New England just invented the forward pass. The Pats have two receivers to the left with only one man covering them and the first down is inevitable.

This was far from an uncommon occurrence. Of all the insane stats Brady put up last season, his quick game splits with and without pre-snap motion might be the craziest of them all.

Passes Thrown Within 2.2 Seconds of Snap

| Stat | With Motion | Without Motion |

| Completions | 125 | 101 |

| Attempts | 170 | 162 |

| Yards | 1398 | 1009 |

| Y/A | 8.22 | 6.23 |

| TD | 13 | 7 |

| QB Rating | 118.2 | 91.8 |

Brady led the league in every single one of those statistical categories with motion – even yards per attempt. It’s as if the Patriots are playing a completely different game than everyone else, and it’s amazing to watch. It’s scary to think that with the addition of Martellus Bennett and return of Dion Lewis, New England’s offense could get even better — and quicker — in 2016.

© 2024 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2024 PFF - all rights reserved.