[Editor’s note: This is the fourth installment in Senior Analyst Mike Renner’s“Teaching Tape” article series, which takes a look at the best positional units across the NFL.]

Defense wins championships. It’s a phrase so simplistic and outdated that it’s usage serves as a litmus test for the quality (or lack thereof) of one’s analysis. From Super Bowls XL to XLIX, the average winner ranked 8.7 overall in points per game (with only one team being below the league average), while they finished 11.2 overall in points per game against (with four teams below the league average). Simply put, an elite offense was more necessary to carry a team to a Super Bowl victory. Last year though, the Broncos' defense won a championship, without much aid from the offense. They were a unit so dominant that offense didn’t matter, and that’s why they're the next team to go under the microscope in the “Teaching Tape‘ series.

The Broncos' pass defense starts from the top down. Wade Phillips didn’t create any baffling new scheme or throw in funky matchup-specific wrinkles into his coverages. Instead, he provided a mindset and philosophy that permeated throughout every level of his defense. If you could boil it down to a corporate mission statement, it would likely be: Let the players make plays.

I know what you’re thinking, “No kidding,” but it’s a concept that’s not ubiquitous in the NFL. Some defenses stress gap control, rush-lanes, and assignments to such a degree that elite guys can get hamstrung and leave potential big plays out on the field. This isn’t to say that each ideology doesn’t have its merit, but more so that it’s easy for a defensive coordinator to say they’ll be more of an “attacking defense” in an introductory press conference than to actually be one on Sundays.

It takes trust. Trust in players’ judgement. Trust in players’ skill. Trust in players’ preparation. It’s that type of trust that Phillips afforded his defense as much as any coordinator in the league in 2015. There are two main ways to be “aggressive” as a defensive coordinator: bring more than four rushers (a.k.a. blitz) or play man-coverage.

| Team | Man Rate |

| Kansas City Chiefs | 48.1% |

| Buffalo Bills | 46.2% |

| Denver Broncos | 45.9% |

| New England Patriots | 43.9% |

| Arizona Cardinals | 43.3% |

| Team | Blitz Rate |

| Arizona Cardinals | 42.6% |

| Denver Broncos | 40.0% |

| Tennessee Titans | 39.6% |

| Oakland Raiders | 37.2% |

| Green Bay | 34.6% |

As you can see from the above table, Denver (along with Arizona) really separated themselves from the pack in terms of aggressiveness. When they did blitz, opposing quarterbacks completed 50 percent of their passes and averaged 5.4 yards per attempt with 10 touchdowns, eight interceptions, and 23 sacks. That’s over 291 dropbacks over the course of the season.

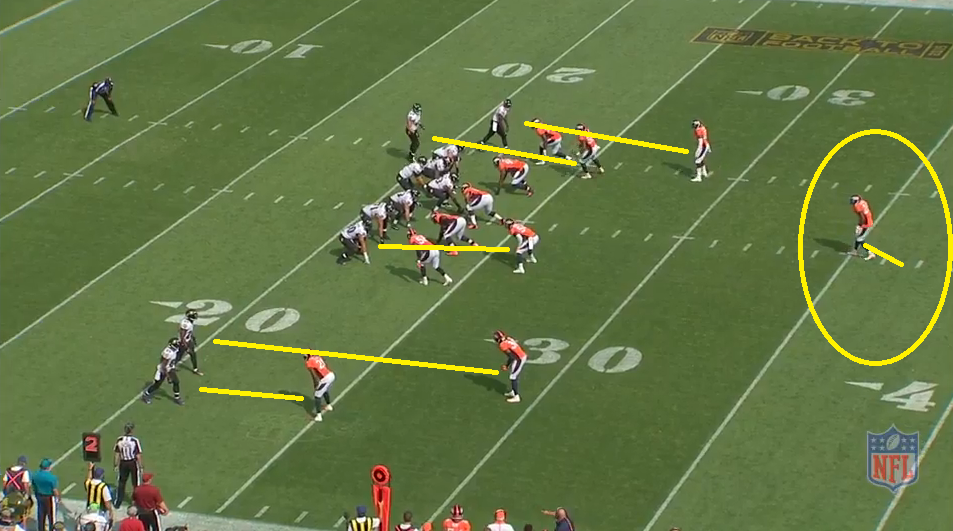

Effective blitzing is all about timing and location. In the play above, the Broncos roll down a safety and overload the weakside of the formation right before the snap. The Vikings should have adjusted their protection as the slide was towards the strength of the formation, but they didn’t have time, and as such, didn’t have enough blockers to prevent the sack.

It’s a little easier to trust in a defense that has the playmakers Denver did along the line. Everyone knows about Von Miller and DeMarcus Ware, but Derek Wolfe and Malik Jackson (now with the Jaguars) were both top-12 graded interior players, while spot-rushers Shane Ray and Shaquil Barrett had higher pass-rushing productivity marks than Julius Peppers. Even when they didn’t blitz last year, they still generated pressure on a ludicrous 46.0 percent of snaps. The average for the rest of the league? 32.6 percent. When you take out all passes thrown within two seconds of the snap and screens (realistically no chance to get a pressure), that number jumps to 57.7 percent for Denver and 43.0 percent for the rest of the league. That means on almost three out of every five normal dropback passes, the Broncos got pressure on the quarterback without a blitz.

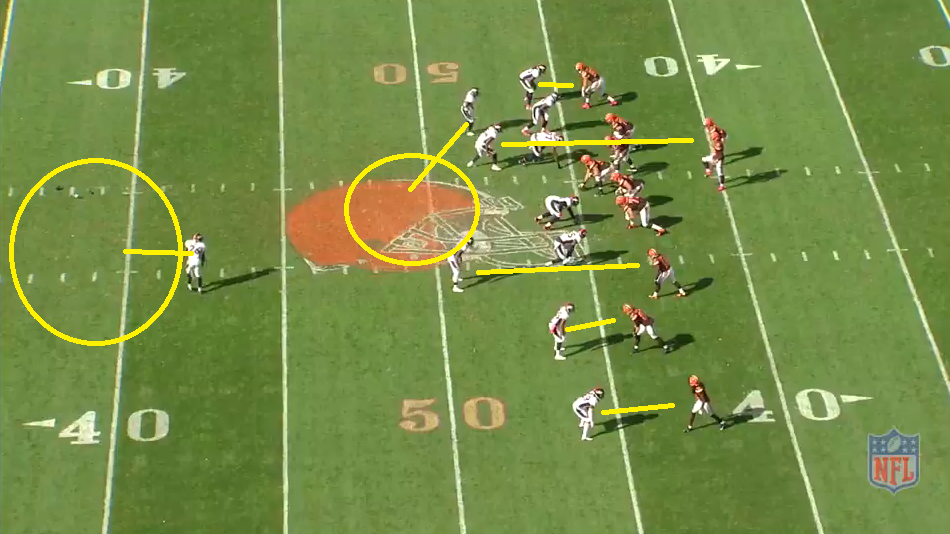

The schematic aspect of the Broncos' pass defense is likely the simplest one of the series so far. Man-coverage has been man-coverage for years. Denver’s favorite variation was cover-1 blitz (26.6 percent), meaning that the only defender playing a zone is the deep middle of the field safety, whereas in regular cover-1 (10.8 percent), there is also an underneath zone defender. The Broncos were also among the league leaders in cover-2 man (5.6 percent), which differs in that the man-defenders play in trail-technique.

Cover-1 blitz

Cover-1

Cover-2 man

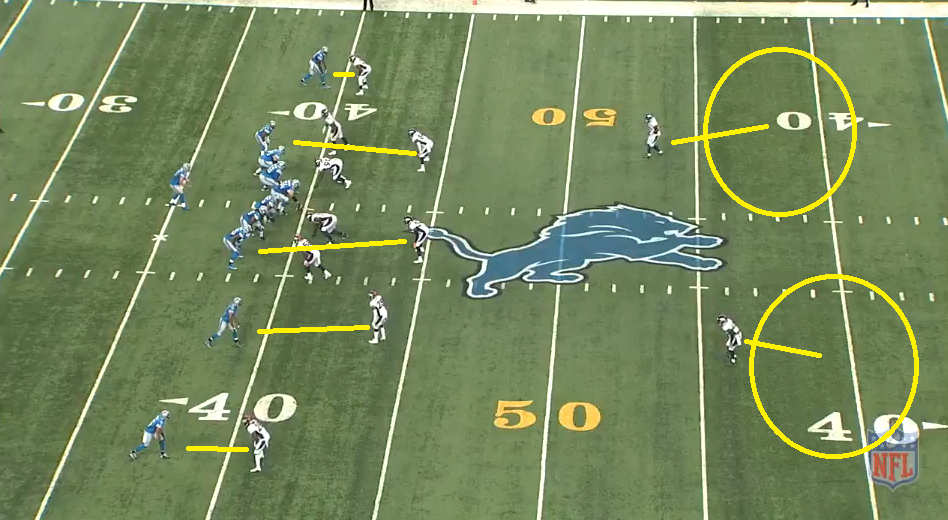

Like the defensive line, it helps when your cornerbacks are freakishly talented and you can play matchups with them because of their size. Aqib Talib (6-foot-1, 205 pounds) would routinely follow any receiver with size, while Chris Harris Jr. (5-foot-10, 199 pounds) or Bradley Roby (5-foot-11, 192 pounds) would be on anyone with quickness. As I said before, this isn’t revolutionary stuff. The Patriots had many of the same quirks on their run to the Super Bowl the year before. The execution, though, is what sets them apart.

Take the play below. The walked-up corners on the outside and the depth of the linebackers and safeties post-snap suggest that the coverage is 2-man. The slot fade that Golden Tate runs is a great route against 2-man when the slot corner has inside leverage like that. On the outside, Roby reads the release of Lance Moore and immediately commits to sinking under the fade, recognizing the route concept. He easily could have been wrong and yielded an easy catch to Moore, but it’s yet another example of the freedom they’re allowed to play with.

No one is blind to the fact that it helps to have four of PFF’s Top 101 players of 2015 at your disposal on the defensive side of the ball. At the same time, though, there have been numerous talented defenses in the past 10 seasons, and none carried an offense as anemic as Denver’s to a championship. If you’re looking to follow the blueprint for their success, good luck. Defenses like the 2015 Broncos don’t come around every year.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.