Last week, we were blessed with a weekend of NFL football that included frequent moral appeals to rushing attempts (and the bonus that was rushing yards, in some instances). Twenty of the 32 teams had to watch the games from home (or the golf course, or Cabo), and one of the notable teams to stay home were the Atlanta Falcons, a team that we on the PFF Forecast have backed numerous times in our articles and on air. A lot of their difficulties this season – they finished 7-9 and were firmly out of the NFC playoff race by the time their Thanksgiving game against the Saints ended – can be attributed to crippling injuries to their young and fast defense. However, it’s difficult not to notice something off with their offense for the better part of the last two seasons.

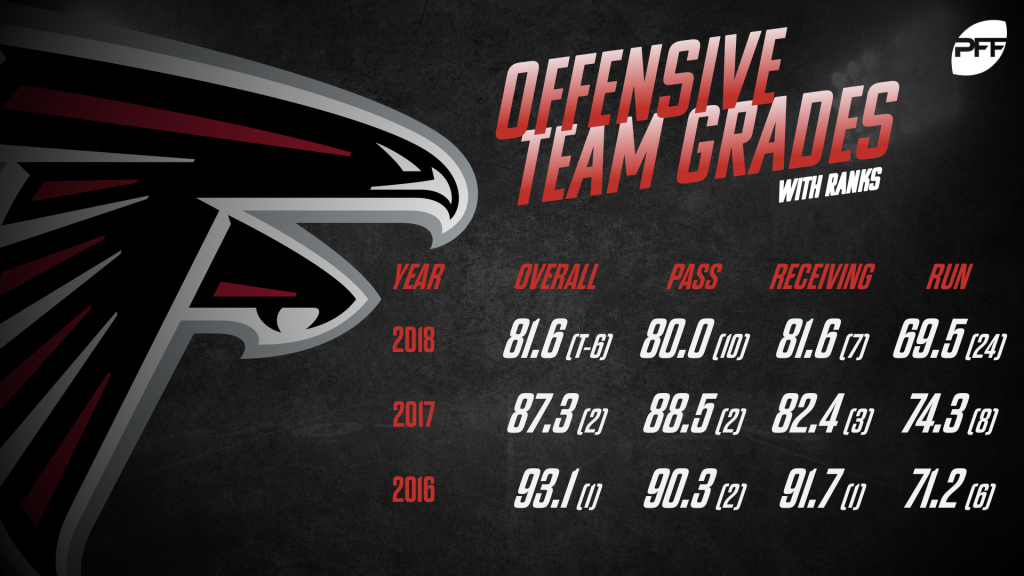

When Kyle Shanahan left his post as the offensive coordinator in 2017 to join the 49ers, Dan Quinn elevated Steve Sarkisian to take his place. Per elementary measurements, this move was a downgrade, as the Falcons’ points per game fell from 33.8 per game with Shanahan (best in the NFL) to 22.1 (15th) and 25.9 (10th) with Sarkisian. Expected points added (EPA) per play tells the a similar, albeit less drastic, story, as the Falcons were number one by a mile in 2016 in that metric, while falling to sixth both years under Sark. In 2017, red-zone efficiency was a big reason for the dip in points per game, as less than half of their trips there resulted in touchdowns, compared to roughly two-thirds of them in 2016. This red-zone efficiency increased to 2016 levels again in 2018, but it did not result in a similar number of points.

Despite the struggles in 2017 and 2018, the connection between Matt Ryan and Julio Jones has been one of the healthier in the league. Matt Ryan throwing to Julio Jones has had a passer rating of 107.1, 93.7, and 109.4, respectively, from 2016 to 2018. One of our signature metrics, yards per route run, combines our player participation data in conjunction with traditional receiving yards to capture how efficient a receiver is whenever he’s given an opportunity in the passing game, has looked upon Julio favorably, as he’s ranked first in that metric in each of the last three seasons among wide receivers. In terms of our wins above replacement (WAR) metric, Ryan has finished third, fourth and 11th the last three seasons, while Jones has finished first, third and sixth at his position group.

Thus, at least upon first blush, blaming the execution of the Ryan-Julio combination would be a big stretch, and hence it’s likely that a secondary element and the razor-thin margins that are afforded offenses at the NFL are the likely culprits for what has ailed the Falcons. Here are a few examples of where the Falcons fell short.

Running too frequently on early downs

Game script matters and much of what constitutes “getting ahead of the sticks” has less to do with execution and more to do with play calling. In the first half of games in 2016, the Falcons threw the ball 55.3 percent on first down, a rate that was 10th-best in the NFL. In 2017 and 2018 these numbers actually got better, to the eighth-best and third-best rates, respectively. However, on second-down plays in close games, their decision making (and success) has gotten progressively worse. In 2016 they made the “correct” decision to run or pass (with respect to which choice had the higher EPA league-wide) 64.3 percent of the time on these game-script-neutral second downs, and they generated a successful play on 46.9 percent of those plays. These numbers plummeted to 56.5 and 56.7 percent in 2017 and 2018, respectively, as have their success rates (43.2 and 43.3, respectively).

With their early-down success in 2016, the Falcons faced the league’s lowest number of third-down plays during the regular season, versus the 13th-most by the time we got to 2018. As one of my academic mentors once told me about species extinction: “it’s easier not to die if you don’t cross the road very often.” The Falcons simply had to cross the road more often the last two years, and even with Matt Ryan and Julio Jones at their disposal, it hurt them just enough for production to suffer.

Not using enough play action

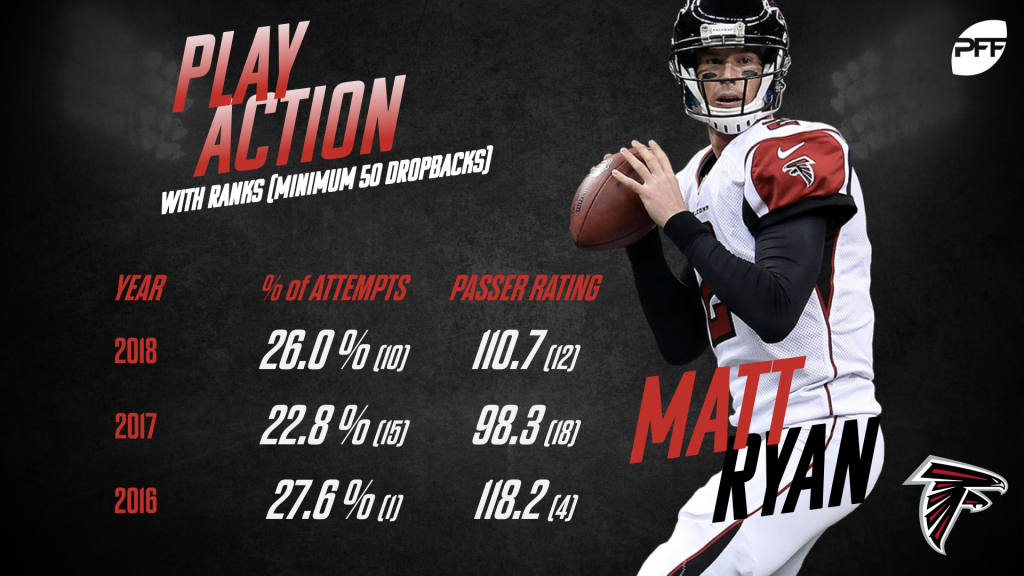

As many have written about, play action is one of the best hacks that a modern offense can use. Passing efficiency goes up league-wide when using play action, and it doesn’t appear to matter whether a team is good at running the football or if they have overused the play fake during a game. In 2016, Matt Ryan not only used play action at a higher rate than any other quarterback (27.6 percent), he was the league’s highest-rated passer when doing so (116.7). For some reason, these percentages went down to 22.8 percent (98.3 rating) in 2017 and 26.0 percent (110.7) in 2018, the latter a year that saw a huge uptick in play-action passing (and hence Ryan finished just eighth in play-action percentage).

Play action is something that every team should do more of, as every single passing efficiency metric of note goes up when a team uses a play fake. The Falcons' inability to come close to 2016 rates of play action until 2018 is something that very much contributed to their offensive difficulties relative to the rest of the league under Sark.

not scheming enough open throws

As luck would have it, we’ve done advanced quarterback charting for every NFL quarterback since the 2016 season, which includes ball-location accuracy and separation. The latter is another place where Shanahan helped Ryan and company thrive in 2016 and where Sark lagged behind a bit in subsequent seasons.

On passes traveling 10 or more yards in the air in 2016, Ryan’s receivers had at least a step of separation on over 56 percent of said throws, which was in the top five in the NFL. These percentages dropped below 49 percent in both 2017 and 2018 (like many things, they did get slightly better in 2018). This drop put Ryan 16th and 13th in the NFL in 2017 and 2018, respectively. Throwing contested passes leads to more incompletions and less predictability with respect to quarterback efficiency. This is precisely what we saw, and while it's not entirely something that should fall on the shoulders of Sark (receivers could have done a better job of getting open, and Ryan could have spotted the open player more often if said player existed), it was not a good look for the club the last two years.

Bad variance

As Falcons apologists (and reasonable human beings), we, of course, have to attribute the downward trajectory from an all-time efficient offense to a middle-of-the-pack one to regression and bad variance. Measures of quarterback efficacy are not stable in situations like pressured snaps, play action, and the red zone. To speak to the red zone, Ryan was second in raw PFF grade per dropback there in 2016, before falling to fifth there in 2017 and 15th in 2018. This is both tied to their drop in scoring in 2017 and 2018 and also more noise than signal.

In 2016, Ryan had 137 third-down passing attempts. Only 5.1 percent of this relatively-low number of passing attempts in said situations were dropped (19th-most among 32 qualifying quarterbacks). In 2017 and 2018 these percentages changed to 9.7 percent in 2017 (worst) and 3.3 percent in 2018 (27th-most of 33 qualifiers). Third-down drops end drives – they kill the opportunity to subsequently throw a touchdown or gain an additional 25-75 yards on the stat sheet. Drop rates are extremely unstable on a season-to-season basis, but like red-zone efficiency, they generate real discrepancies in this outcome-driven world of football.

This bad drop variance has led to more turnovers for the Falcons offense. Less than 27 percent of Ryan’s turnover-worthy passes were intercepted in 2016 (the least in the league), while in 2017 that number jumped to 66.7 (before going back to 30.8 in 2018). Thus, much like third-down drops, the variance was not on the Falcons' side in 2017, and good variance was not enough to elevate them in 2018, especially when Ryan’s processes (e.g., PFF grades) were even just slightly lower.

This list is certainly not exhaustive, but it gives you some of the reasons why, despite an encouraging amount of talent and some impressive individual statistics for the Falcons, their offense was ultimately unable to carry their team and keep their coordinator’s job after just two seasons. In a league where the gaps between the great, mediocre and poor offensive minds appear to be widening, it’s imperative for the Falcons to find someone capable of taking advantage of a truly great quarterback-receiver combination, an offensive line that (at times) has been good enough at keeping Matt Ryan clean, and a stable of support in Calvin Ridley, Mohamed Sanu, Austin Hooper and Devonta Freeman that can compete with anyone. Is Dirk Koetter that answer? We’ll see.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.