It’s been a few months since we published this study, which explores the idea that coverage is more important than pass rush in the NFL today. This received a wide range of reactions but got the conversation started about what it means to be successful as a modern defense.

We also published an article recently on a quarterback’s contribution to his own pressure. It became pretty clear (understandably) that time in the pocket was the most important variable determining whether a pressure occurred on a play. An immediate question with respect to defending the passing game is which defensive factor contributes to time in the pocket?

To answer this question, we took our play-by-play grading and adjusted it for replacement-level for each player for the previous two seasons and that season. We aggregated these player-level grades by each facet, pass-rushing and pass coverage, for all players who played for a given defense that game. Thus, for each play, we had a measure for how good that team was rushing the passer and in coverage up until that game.

[Editor's Note: These grades are a part of our PFF Greenline algorithm for both the NFL and NCAA. PFF Greenline will be LIVE and made available to all ELITE subscribers in August 2019. Check it out!]

First, a bit of background on time in the pocket data. This data partially reflects the decision of the quarterback and the environmental bestowed upon him. If a quarterback is prone to running around in the pocket, he will have a higher time in the pocket, whereas if a quarterback is in a scheme that favors shorter, quicker passes, he will have a lower time in the pocket. There is some statistical evidence that stronger receiving grades correlate with lower time in the pocket, but lower times in the pocket correlate (slightly) with higher play success (as measured by expected points added) on all dropbacks. In other words, the risk (e.g. of a sack, late pressure, or an ineffective scramble) associated with hanging onto the ball longer is slightly higher than the benefit (throws further down the field, positive outcomes from the scramble drill). However, if there is no pressure on a play, time in the pocket (expectedly) correlates positively with play success. Thus, from a defense’s perspective, it’s clear coverage’s job is to get the quarterback to hang on to the ball longer and the pass rush's job is to get the quarterback to get rid of it more quickly.

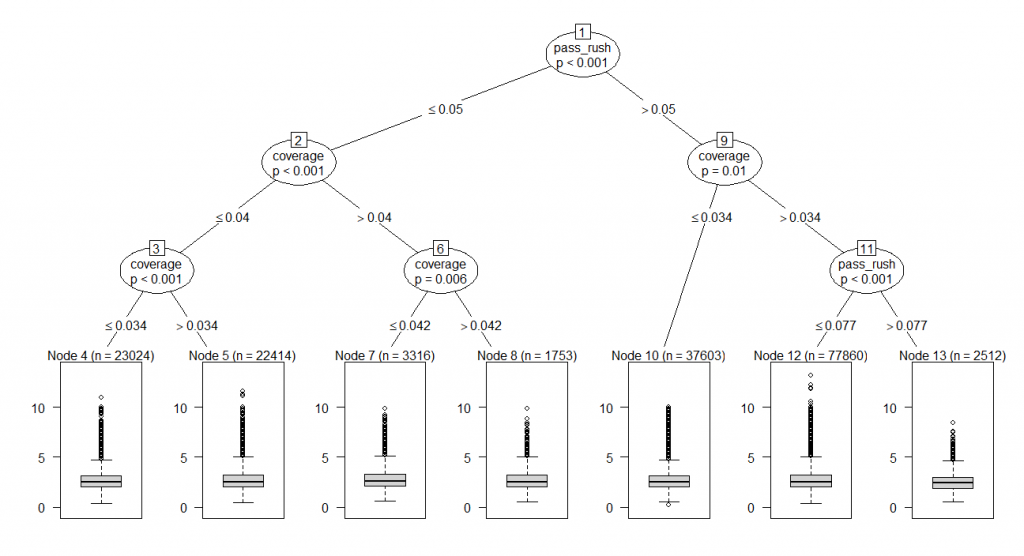

This is exactly what we see in our play-by-play data. Our aggregated coverage grades correlate at the play level with time in the pocket at a rate of 0.012 (p < 0.01), so better coverage units force longer times in the pocket. On the other hand, pass-rushing grades correlate at the play level with time in the pocket at a rate of -0.016 (p < 0.01), so better pass-rushing units force quicker throws and affect at a slightly higher rate. In a simple linear model, the interaction between the two variables is statistically significant, which is a stronger conclusion about that relationship than what we came to in our original article, which aggregated by facet at the team level. Other, more sophisticated models point in the same direction, that both pass rush and coverage are important predictors of time in the pocket, which is good validation for both our hypothesis and our grades here at PFF. When additional “contextual” variables, like down and distance, are folded in, they similarly hold, meaning we are likely not conflating pass rushing and coverage with a lurking variable that skews the results.

Figure: A decision tree for time in pocket. More-important variables split nearer to the root of the tree (the top of the diagram), with less-important variables splitting the tree thereafter.

While this study might seem like giving more weight to pass-rush than our initial study – some caution is in order. First, the strength of a team’s pass rush is (theoretically) known a priori through game planning, so an opponent usually has the balance of the week’s preparation to scheme quicker throws, and quicker throws are every bit as valuable (if not more valuable) than longer-developing throws, especially when they are intentional. This is why, when one digs into the data deeper to see how to play success is predicted by opponent pass rushing and coverage, coverage abates play success at a much higher rate than pass rush, with or without adjusting for contextual variables.

Thus, the takeaway from this piece is a pushback against any notion that pass rush doesn’t affect offenses. It certainly affects offenses, forcing them to throw more quickly than coverage forces them to hang onto the ball. The issue for pass rush, however, is that quick passes are often effective, and so in terms of moving the needle defensively, it’s important to be able to cover well.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.