Sacks are one of the most game-changing plays in all of football.

Sacks force fumbles.

Sacks end drives.

Sacks are, at least up until Pro Football Focus came onto the scene, how we judged pass-rushers. However, sacks are not a particularly-stable statistic compared to other measures of rushing the passer. During the PFF era (2006-2017), sacks have been correlated season-to-season at a rate of 0.489 (r-squared of 0.239) for players with 150 or more pass-rushing snaps in consecutive seasons. Pressure rates and pass-rushing productivity (PRP), on the other hand, are correlated at rates of 0.711 (0.505) and 0.717 (0.515), respectively. This means that more than half of the variability in how a pass-rusher performs one season (assuming they are healthy) can simply be gleaned from how they performed the season before. Both of these pressure metrics predict sacks in subsequent seasons better than sacks themselves, with pressures and PRP correlating with sack rates of 0.548 (0.301) and 0.555 (0.309), respectively, both explaining more than 30 percent of the variability in sacks season-to-season.

So if pressure rates are a better means to evaluate pass-rushers, then why do we care so much about sacks again? The answer to that is simple: because they add so much value.

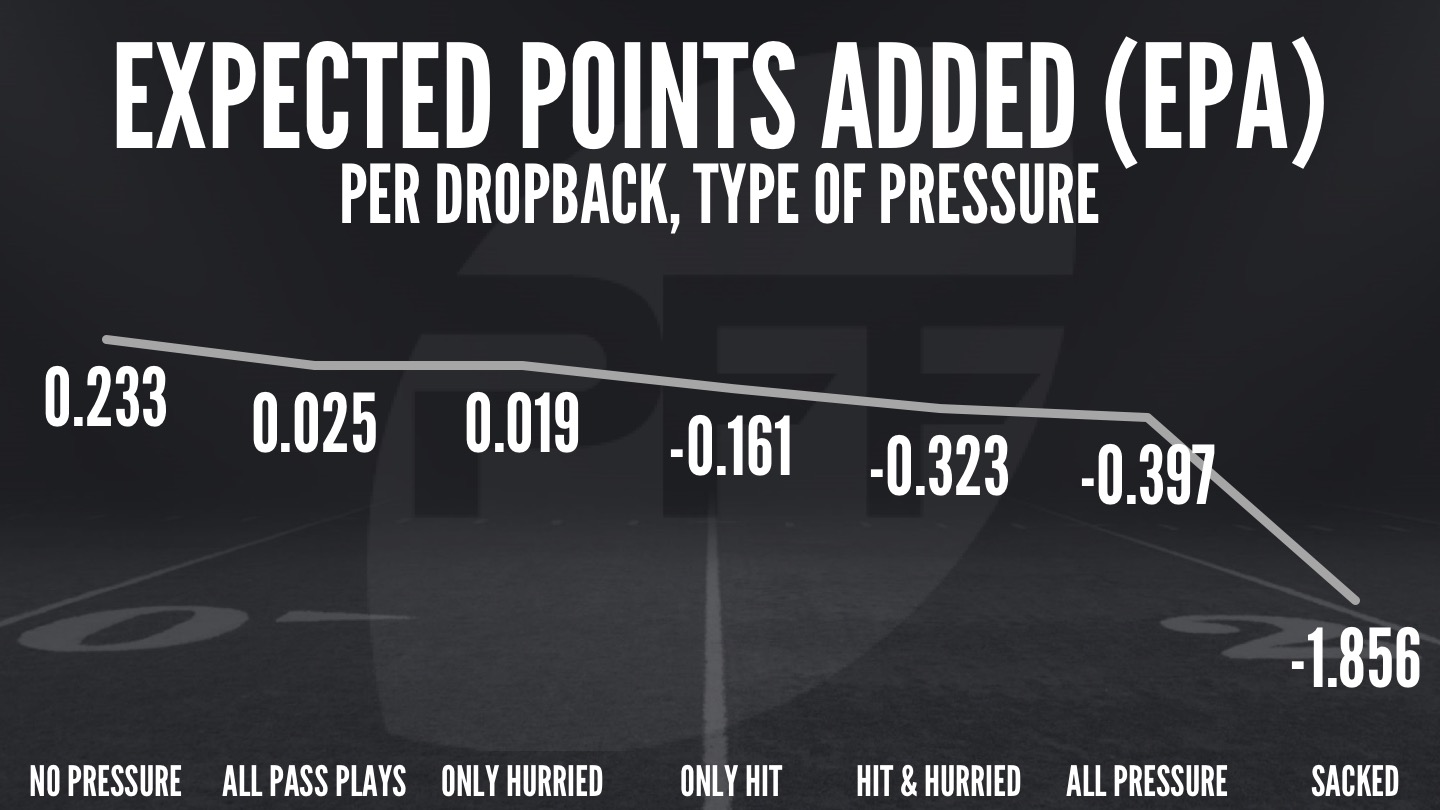

Using our Expected Points Added (EPA) model, we know exactly how much each impact play by a defender affects opposing offenses, with a positive EPA implying a successful play by an offense and a negative EPA a successful play by the defense.

- EPA on all passing plays: 0.025

- EPA on all non-sack passing plays: 0.145

- EPA on passing plays without pressure: 0.233

- EPA on passing plays with pressure (incl. sacks): -0.397

- EPA on passing plays with pressure but no sack: -0.074

- EPA on passing plays where the quarterback is only hurried: 0.019

- EPA on passing plays where the quarterback is only hit: -0.161

- EPA on passing plays where the quarterback is only hit and hurried: -0.323

- EPA on passing plays that result in sacks: -1.856

Notice that, on average, passing plays are a net positive for an offense, and passing plays that do not result in pressure are even more so. Once pressure is applied to a quarterback, passing plays become a negative proposition for an offense, but are an order-of-magnitude worse when they result in sacks.

So what does this mean for our understanding of pass-rushers using PFF data? First, sacks (and results) matter – they explain a great deal of what happened in a given season. The 2016 Atlanta Falcons’ defense was buoyed in many ways by the play of Vic Beasley and his 15.5 sacks, for example. However, sacks are not the best way to project pass-rushing efficacy moving forward: Beasley’s relatively-weak pressure rates (18th among 3-4 outside linebackers in PRP in '16) in relation to other similarly-statured edge defenders was a cause for concern, and his fall to five sacks in 2017 somewhat predictable.

The 2017 Super Bowl Champion Philadelphia Eagles spent a 2013 first-round pick on Brandon Graham, an edge defender who never eclipsed 6.5 sacks in a season, causing many to label him a bust. However, pressure numbers have always reflected positively on Graham, as he was the third-most productive 4-3 defensive end in terms of PRP in 2016, trailing only Cameron Wake and Mario Addison, despite collecting only six sacks. This process led to results in 2017, as he generated 11 sacks in the regular season and a game-altering one in the Super Bowl, earning the Eagles their first title.

Statistics and metrics come in many forms. Some (sacks) are more descriptive than predictive – some more valuable when they occur in real time but difficult to use to project game-changing behavior in the future. Some (pressure numbers) go relatively latent for a period, adding bits of value on a consistent basis, but lacking in the eye-popping events that we remember. Often the latter can better predict the former, though, meaning we must have a constant conditioning of our eyes as football analysts.

[For more information on Expected Points Added and other deep dives into football analytics, follow the PFF Forecast Pod and @PFF_EricEager & @PFF_George on Twitter.]

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.