Bill Belichick’s ability to game plan opponents has grown to near mythical proportions over the years. In the lead up to this weekend’s Super Bowl, it’s almost assumed that he’ll find a way to take away the Falcons' No. 1 receiver, Julio Jones. Now, the Patriots haven’t exactly shut down true No. 1 receivers this season (Pittsburgh's Antonio Brown and Cincinnati's A.J. Green combined for 271 yards on 20-30 targets in three combined games this season), but that’s not necessarily the point. The track record is stellar, and even with good numbers, those offenses were still limited to under 20 points each matchup.

When designing coverages to deal with elite receivers, there are a handful of things you can do as a defense (and New England did all of them in the AFC Championship at some point against Antonio Brown):

1. Do nothing different (ask the Panthers how this went).

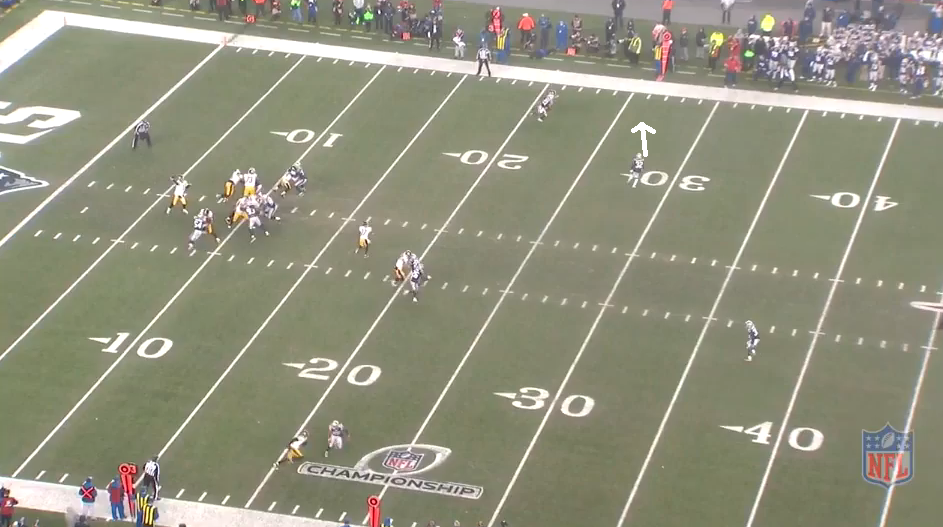

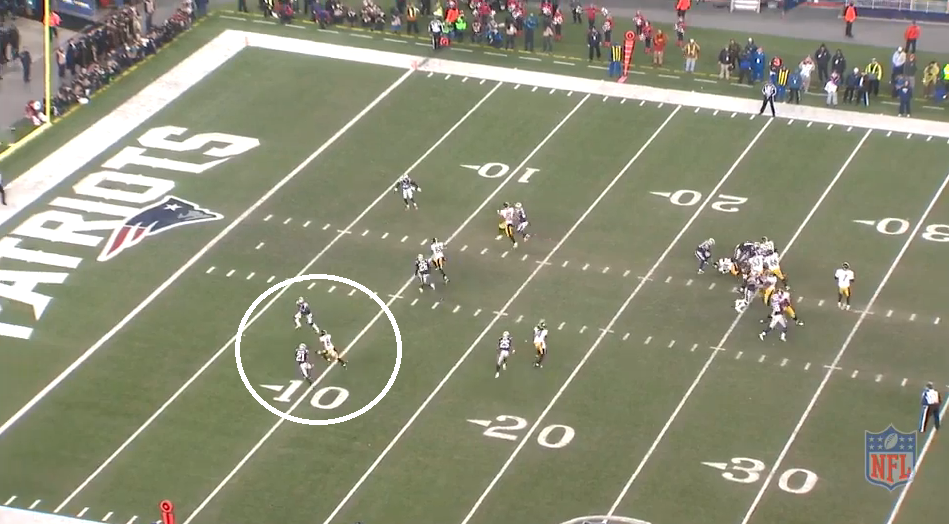

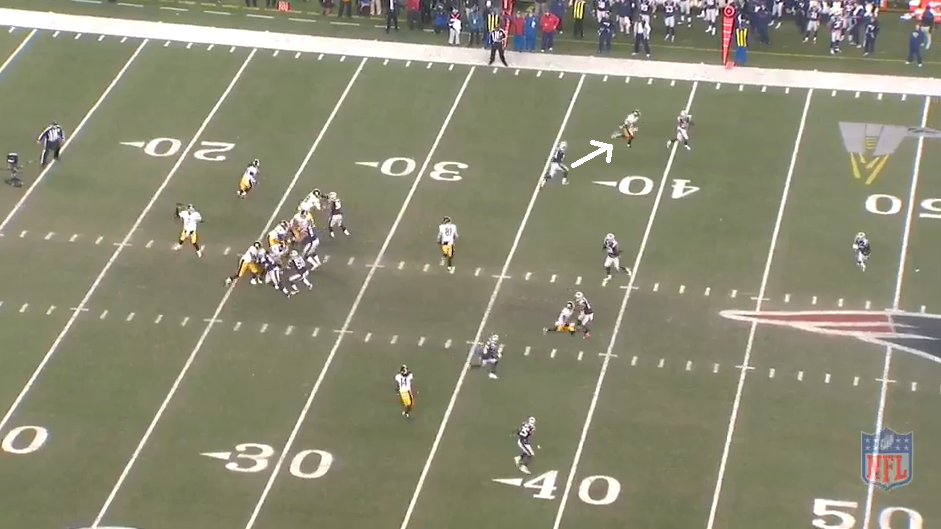

2. Lean a safety over the top.

3. Bracket (double team).

4. Dedicate an underneath defender.

5. Drop eight into coverage (we’ll get to this later).

The Pats don’t have a “base” coverage that they fall back on, and they’ll employ anything they believe gives them a matchup advantage. All of these options are on the table this Sunday. Now, let's dive into what makes New England's coverage unique.

How they play matchups

The most obvious thing that New England does in coverage that is slightly out of the norm is have certain corners follow certain receivers throughout the game. Now, this doesn’t necessarily mean they are sitting in man coverage all game, but even in most zone coverages, the cornerback will at least defend the receiver he’s lined up across from for a portion of the route. This also doesn’t mean that the Patriots have a Darrelle Revis-esque No. 1 corner following the opposing team's No. 1 receiver regardless of the situation. The matchups are far more attribute-based than that.

Putting a shorter corner like Malcolm Butler on A.J. Green is going to create a mismatch. So is putting a slower corner like Logan Ryan on Antonio Brown. The goal is to decrease those skill-set mismatches as frequently as possible and put players in favorable positions.

Over the course of the regular season, the Patriots shadowed opposing receivers 11 times, the second-most of any team in the NFL. With the stark contrast that the Falcons' receivers present, it’s extremely likely they track receivers come Sunday. The conversation then becomes who follows whom? Julio Jones’ size is a mismatch for Butler, while his speed is a mismatch for Ryan. The interesting option is whether or not they feel comfortable using second-year CB Eric Rowe—who possesses both the size and speed—but doesn’t have the track record to defend Jones.

Unpredictability

While opposing quarterbacks may know which cornerbacks will be lined up over which receivers, this doesn’t give them any insight into what the coverage will be post-snap. New England played man coverage at the seventh-highest rate in the NFL this season, but that still only accounted for 45.4 percent of the team's defensive snaps. And even as such, not all man coverages are created equal. The Patriots played the third-most man coverage with two deep safeties in the NFL, and have numerous other wrinkles they mix in.

By far the most interesting one is the way the Patriots implement their blitz packages, or lack thereof. New England blitzed on 25.2 percent of their opponents' dropbacks this season, just the 26th-highest rate in the league. But Belichick takes not blitzing a step further. The Patriots only rushed three defenders or fewer on 26 percent of their passing snaps this season. That’s so far and away an outlier in the NFL today; the Cowboys are the next closest, at 19.3 percent, while the majority of teams are under 10 percent. And this isn’t purely a third-and-long tactic. On first downs, New England used it 21.3 percent of the time—and on every single down, except for fourth, they are more likely to rush three players than to blitz.

The downside to rushing three is obviously giving more time to opposing quarterbacks. However, there are certain advantages to dropping eight into coverage that the Patriots obviously believe outweigh the cons. The first is that it allows for double-teams without messing up the structure of a defense. A double team with a normal four-man rush is usually going to remove a critical underneath zone player, but with a three-man rush, both are present.

The second is the ability to man-up a player in a zone coverage. If a defense is worried about losing track of a receiver in their zones, they can have seven defenders play a normal zone call and then one defender follow his receiver in man.

The final benefit is that it can shut down screen games. Running back and receiver screens rely on defensive linemen taking themselves out of the play naturally. Most screen designs can’t account for that extra man dropping, leaving him a free run at the targeted receiver. Unsurprisingly, the Patriots allowed all of 77 yards on screens this year. The next closest team was the Buccaneers, at 164, and the league average was 315. Those are free yards that New England refuses to allow.

Taking everything here into consideration, the Patriots may implement none of the strategies come Sunday, or possibly all of them. That’s the beauty of New England's ever-evolving piecewise defense in. If Belichick and company are the first team to stymie the Falcons' offense since Week 10, it will come as a surprise to no one.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.