The Dallas Cowboys rebounded from a disappointing, playoff-less 9-7 campaign in 2017 to win the NFC East in 2018. They finished with a 10-6 record and a playoff win against the similarly-rebounding Seattle Seahawks before they bowed out to the eventual NFC Champion Los Angeles Rams in the divisional round.

Quarterback Dak Prescott continued to struggle to live up to his stellar rookie campaign and finished with our 18th-best quarterback grade (74.6), and a middling (for a quarterback) wins above replacement (WAR, 1.71) number. Mid-season addition Amari Cooper teamed with Cole Beasley to add about a win over replacement in the stead of the departed Jason Witten and Dez Bryant, while the defense took a substantial step in the right direction, cultivating success with emergence of young players like Byron Jones, Jaylon Smith, Leighton Vander Esch, and Demarcus Lawrence.

I’m obviously leaving one notable player from this discussion. Running back Ezekiel Elliott has been one of the most productive running backs in the NFL since joining the league as the fourth-overall pick back in 2016. He’s averaged over 100 rushing yards a game — leading the league in that category each season — added almost another 1200 yards through the air and scored 34 offensive touchdowns. All that said, some readers have astutely pointed out that Zeke earned only the 30th-highest rushing grade among running backs last season (71.7). How can that be? Do we not think Zeke is a good running back? I answer a few of these questions below.

Of course, we at PFF think Zeke is good, but all backs are

A caveat, though: I personally think all running backs in the NFL are good. Or, at least I think that the rushing production function in the NFL is not very sensitive to how talented a running back is. In our article on the replaceability of running backs in the NFL, I showed that the skill of the running back (as defined by PFF grades above or below average) does not predict play-by-play rushing success once one adjusts for situation, offensive line grades, run concept and the number of defensive men in the box.

This was never more apparent than when Zeke was out in 2017, when both Rod Smith and Alfred Morris filled in admirably. Dallas was actually twice as efficient running the ball in the six games that Elliott missed via suspension, averaging +0.04 expected points added (EPA) per run play during that stretch.

He’s not as good as he should be

We use a Massey-type rating system using PFF run-blocking and run-defense grades to adjust our play-by-play grading by opponent and rank offensive lines in run blocking (they are what help Mike Renner create lists like these). The last three seasons, the Cowboys offensive line has ranked fourth, second and sixth, respectively.

While offensive line rankings correlate well (r = 0.52) with EPA per running play, the Cowboys actually performed worse than would be suggested by their offensive line, finishing 12th in EPA generated as an offense per run play (-0.06 per). The Cowboys offense averaged -0.02 EPA per Zeke run (-0.04 if you count playoffs), which is still lower than one would expect with an offensive line that effective.

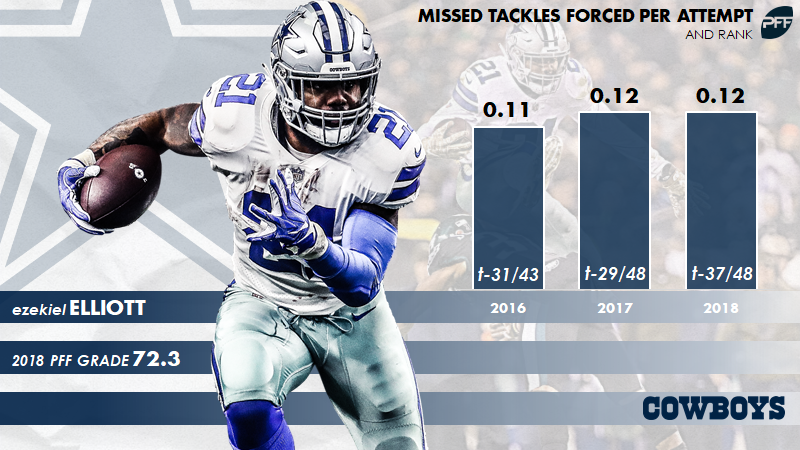

Zeke doesn’t force missed tackles as much as others do

As we and others have noted, a running back’s ability to break tackles is his one stable trait as a player. Specifically, our Elusive Rating, which not only captures how often one breaks tackles in both the passing game and the running game but also what they do when they break a tackle, was not kind to Elliott in 2018. He was 35th in the metric (37.7), behind players like Todd Gurley (tied for 33th with Chris Ivory), Alvin Kamara (31st), Christian McCaffrey (26th), Adrian Peterson (13th), Chris Carson (12th), James Conner (11th), Melvin Gordon (9th), Saquon Barkley (8th), Kareem Hunt (4th), Derrick Henry (3rd) and Nick Chubb (2nd).

Zeke was 40th in this metric in 2017 and 31st in 2016. A lot of our grading system tries to divorce what a running back does versus what his offensive line “gives him.” A running back that doesn’t break a great deal of tackles will hardly ever earn a grade that their (volume-based) production would appear to imply.

Another of our other Signature Stats, Breakaway Percentage, measures the percentage of yards a running back gains on runs of more than 15 yards, was also not very kind to Zeke, who finished 15th in that metric. This isn’t one of our more stable metrics, but it demonstrates a relative lack of the Derrick Henry-on-TNF-like big plays that would substantially lift Elliott in our view.

Fumbles, fumbles, fumbles

One of the reported reasons why (all) teams run more than they should is the relative safety that the running game provides. Fumbles turn this idea on its head, and Zeke lead all running backs in fumbles not occurring on kick or punt returns, with six. Fumbles are downgraded significantly in our grading system – providing another explanation for Elliott’s relatively-low PFF grade.

Okay, but didn’t Zeke offer more in the passing game in 2018?

To be short, yes. Zeke’s 77 receptions in 2018 were 19 more than his first two seasons combined. While running back targets are the least-efficient pass plays in the NFL, they are still, play-for-play, more efficient than running so anything that a back can do in this realm is valuable to his team.

Yards per Route Run, our receiving Signature Stat for running backs, measures how efficient a back is when he goes out for a pass route. Elliott was 24th in this metric as a rookie, didn’t qualify as a second-year player, and finished 19th there in 2018 with 1.38 yards per route run, just ahead of Todd Gurley (1.37) and below the likes of Kareem Hunt (15th), Saquon Barkley (13th), Christian McCaffrey (8th), James White (7th), Melvin Gordon (5th), Alvin Kamara (4th) and Tarik Cohen (1st). Thus, while Elliott was productive for the Cowboys in the passing game, it was, like as in the running game, very much a product of volume and not elite efficiency.

Conclusion

You can do worse than Ezekiel Elliott, a player that has produced yards and touchdowns when given a ton of volume for the Cowboys during his brief three-year career. That productivity has accompanied team success despite what many believe to be poor offensive playcalling and 51 total starts by a fourth-round quarterback out of Mississippi State during that stretch.

That said, the running back position is such that (a.) Success is a product of those around you more than any other offensive position and (b.) High-end efficiency is fleeting. Correlation in WAR season-to-season for running backs is roughly 0.4, 80 percent of that for wide receivers and tight ends, and 67 percent of that for quarterbacks. The risk you run as a team with a player like Elliott is feeding him the ball too much to justify his existence, without the predictable efficiency to follow. This approach has led to some historically-hilarious seasons like Ricky Williams’ 392 carries at 3.5 a carry with the Dolphins in 2003 and Larry Johnson’s 416 carries at 4.3 a carry with the Chiefs in 2006 (or Le’Veon Bell’s 316 carries at 4.0 a clip with the Steelers in 2017 to put a modern twist on it), just to name a few. These have invariably left both the running back and his team worse for the wear as a result, allowing them to briefly ignore bubbling issues at more important places on the field – opting to kick the proverbial can down the road.

The Cowboys understood this last point to a degree, sending a first-round pick to Oakland to acquire Amari Cooper to help Prescott on the outside. He responded by generating almost as many WAR during his partial season than Zeke did for the entire campaign. How well he and Prescott can perform with new offensive coordinator Kellen Moore will go far further towards how competitive the Cowboys will be in the NFC East moving forward than how well Zeke does with the ball in his hands. If it does not go as well as planned, we may get more productive years from Zeke accompanied by questions as to why his grade isn’t very high as a result, questions we’ll gladly answer.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.