The story of Week 4 of the 2021 NFL season revolved around the young quarterbacks ascending to the top of the NFL hierarchy — Kyler Murray, Dak Prescott, Lamar Jackson and Patrick Mahomes are leading the way for their respective franchises. And the fresher faces — Justin Herbert, Trevor Lawrence, Joe Burrow and Justin Fields — all seem to be catching up to the speed of the pro game and flashing the attributes that made each a first-round pick.

The four likes and dislikes we cover each week thread together the film and PFF data to identify the trends and tendency breakers from teams across the league. Here are four likes and dislikes from Week 4.

Click here for more PFF tools:

Rankings & Projections | WR/CB Matchup Chart | NFL & NCAA Betting Dashboards | NFL Player Props tool | NFL & NCAA Power Rankings

Like: Kansas City’s Balance

Andy Reid can smell a defensive coordinator’s fear from across the field.

On Reid’s Sunday visit to his old stomping grounds of Lincoln Financial Field, the Kansas City Chiefs controlled the game in a way you don’t often see from this offense: pounding the ball efficiently to set up the play-action passing game.

Coming into week four, the Philadelphia Eagles’ coverage unit allowed the lowest average depth of target in the NFL over its 104 snaps, at six yards. Not only is this unit forcing the ball to be thrown short, but the defense also isn’t disguising its soft zone coverage. Through the same three games, the Eagles rank last in the NFL in snaps showing press coverage (15) by a significant margin. The team with the second-fewest press looks, the Cleveland Browns, had almost quadrupled Philadelphia.

A defense that’s playing off coverage, dropping linebackers deep into zones and/or playing with two deep safeties is just like standing at 16 on the blackjack table. The strategy is one part conceding and one part (figuratively and literally) gambling. An offense either can’t or won’t try to make its living underneath, and an aggressive opponent will overplay its hand looking for every win it can find.

Reid has been justifiably credited with many innovations on offense, but my favorite part of his approach to the sport is his elite conceptual understanding of the layers within balancing an offense.

| Chiefs' Play Call Rates | Run/Pass Split | RPO Rate | Play-Action Rate |

| Weeks 1-3 | 33/64 | 27% | 29% |

| Week 4 | 43/57 | 33% | 44% |

We’re conditioned in our consumption of football to think about balance in the binary of run and pass. In an era of efficient passing offenses, we’ve expanded the context to include which and how many players are able to touch the ball throughout the game. But, the ultimate mark of balance is a combination of the two, understanding balance as a matter of where the ball is going instead of who has it.

| Players | Touches or Targets |

| Clyde Edwards-Helaire | 16 |

| Darrel Williams | 12 |

| Tyreek Hill | 12 |

| Travis Kelce | 6 |

Reid was content to use the RPO and straight-ahead run game to attack the short area of the field. His two-back tandem of Darrel Williams and Clyde Edwards-Helaire worked in the box, and Tyreek Hill and Travis Kelce worked in the seams and on the sideline.

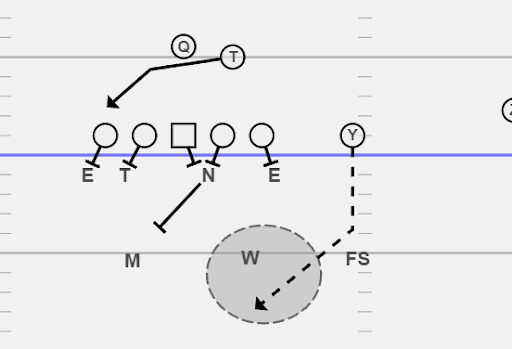

Because the Chiefs employ a spread offense, they need to find creative ways to create additional gaps, or eliminate defenders looking to fit the run. Their answer in the RPO game is to run a version of wide/outside zone to get lateral movement and buy time for Patrick Mahomes to make his read. The scheme operates on a simple counting system, much like a pass protection design: The line counts out and blocks the most dangerous five defenders, and the quarterback and running share the responsibility of eliminating the sixth.

The better the returns the Chiefs found in their RPO game, the more flat-footed linebackers needed to play. This opened the door for a style of bootleg and deep pockets in the play-action game that most shotgun offenses (especially Kansas City) aren't able to access as often.

With the underneath game forcing linebackers to play more still or downhill, and intermediate throws forcing safeties to do the same, there are more opportunities to get right back over the top of the defense. The moment the Eagles blitzed and played man, they were bitten by an explosive play.

No one would argue that the best version of this offense is played over the top, with throws in the intermediate and deep areas of the field. When a defense’s entire identity is taking those play calls off the table, there have to be other ways to punish a defense. Taking what the defense concedes isn't just the most efficient strategy — it’s the best way to open up opportunities for the explosive passes you may want later in the game.

| Pass Type | Rate, Weeks 1-3 (123 Dropbacks) | Rate, Week 4 (36 Dropbacks) |

| Bootlegs | 6% | 14% |

| Screen | 10% | 22% |

| Deep Attempts | 12% | 6% |

| Quick Game Attempts | 13% | 25% |

One thing setting up another is difficult to quantify in a sport with sample sizes as small as the NFL, but a team’s commitment to its game plan does have an effect on the decision-making matrices that exist in the heads of players and coaches. Andy Reid won the chess match against Nick Sirriani’s Eagles by balancing out the attack and forcing the defense to honor every blade of grass.

Dislike: The Giants’ Defensive Regression

New York Giants head coach Joe Judge and defensive coordinator Patrick Graham are running my least favorite style of defense: bend, but also break.

After a surprisingly adequate performance in the 2020 season from the Giants’ defense, the unit has tumbled right back to the bottom of the league. Graham’s unit has allowed the fourth-worst expected points added per play figure through Week 4.

I wanted to be sure there weren’t any major structural changes that may better contextualize the issues they’ve had getting stops this season, so we will compare some data between the 2020 season and what’s happening now.

| Giants' Run Defense | Avg. Depth of Tackle | TFL/NG Rate | Run-Defense Grade |

| 2020 Season | 4.06 | 17% | 73.4 |

| 2021 Season | 3.84 | 9% | 58.1 |

Today, the idea of a dominant run defense is completely opposite from what we once knew — even in comparison to last decade.

Now, with how dangerous early-down passes can be to generating explosive offense, the level of investment to create tackles in the backfield is lower than it’s ever been. However, there needs to be an element of keeping offenses not just off-schedule, but far behind it.

This season, New York simply has not created enough negative plays in the running game to force obvious passing downs. 2020’s 17% rate of forcing a tackle for loss or a rush for no gain has been halved early in 2021. Against the New Orleans Saints, the Giants could muster only two tackles for loss or no gain. Only the uninspiring run defenses of Philadelphia and Kansas City had fewer in Week 4.

New York's average depth of tackle this season (3.84 yards) on runs is more than fine on its own, currently ranking as the ninth-best in the NFL. But to have just nine tackles for loss or no gain — tying for dead last in the league — means that offenses don’t ever have to fear any negative consequence for handing the ball off.

What’s worse, over 70% of New Orleans’ 170 yards gained on the ground came after contact, evidence of a fundamental tackling issue that the scheme cannot fix. The Giants' 14 missed tackles against the run in Week 4 were the most in the NFL, and their 25 over the season is three away from the top of the leaderboard.

In coverage, it’s important to identify what a defense is setting out to accomplish to judge it in its proper context. The Giants were a soft zone coverage team last season and continue to be that now, and there are plenty of reasons to lean on zone to protect your players from matchup problems.

| Giants' Coverage Production | Completion % | Avg. Depth of Target | % of Passes Gaining 15+ Yards | Coverage Grade |

| 2020 Season | 71% | 7.7 | 14% | 55.7 |

| 2021 Season | 79% | 7.4 | 16% | 60.8 |

In playing so little man coverage (sixth-lowest rate of Cover 1 in 2021), having a strong pass rush to add a layer to your defense is a necessary condition. In understanding the layering of the field (short, intermediate and deep), it’s not possible to play coverage at all three levels without distorting the balance of a defense.

Quarterbacks decades ago used to progress from “touchdown-to-checkdown,” and zone coverage was designed with that paradigm in mind. Play coverage on the deep and intermediate areas of the field, and the pass rush will affect the quarterback on his way to the checkdown.

Teams that want to protect against explosive passes while investing in more of a pass rush will run zone blitzes, rushing five or six defenders and playing zone behind it, and that is growing to be the identity of this season’s Giants defense, which ranks last in Cover 1 usage when blitzing. This is an expensive way to defend offenses, and if you’re removing a player from zone coverage to get after a quarterback, you had better get home.

| Giants' Pass Rush | Pressure Rate | Pressure Conversion Rate | Blitz Rate | Quick Pressure Rate |

| 2020 Season | 42% | 21% | 28% | 18% |

| 2021 Season | 41% | 12% | 31% | 20% |

New York is failing to affect the quarterback this season, whether there’s a blitz on or not. In spite of ranking in the top 10 in blitz rate, the team ranks in the bottom 10 in pressure rate and fourth-worst at converting pressures into sacks. The pass-rush scheme struggles to manufacture unblocked pressure (20th in the NFL) and can’t find quick wins (second-worst in pressure under 2.5 seconds). Oftentimes, these zone blitzes are stonewalled, and the quarterback has time to replace the blitzing defender with a throw into a vacated window.

It’s important to note that there may be some noise in the results. But, to have played three consecutive offenses that either lack a run game or key threats and have little to show in how the unit’s performed through four weeks is concerning. Still, this is a sport of small and inconsistent samples. It doesn’t require much to become a losing defense, which is where this team finds itself.

An inability to dictate the game flow to an offense, make tackles at all — especially in the backfield — and isn’t playing any better or tighter in coverage is how the G-Men find themselves with the sixth-lowest defensive success rate in the NFL.

Like: Fitting the Run in Odd Spacing

Typically, I’d pair my two dislikes together to finish on a positive note, but poor tackling leaves a bad taste in my mouth.

The Los Angeles Chargers serve as my palette cleanser coming off this week. And while there are some statistical implications behind the clips we’re covering here, I’d much rather hone in on the techniques that make a scheme go.

Phasing back into an NFL that embraces two-high safeties and the 3-4 defensive structure means there’s a much different context to the way things play out at the line of scrimmage. PFF's Seth Galina and I discuss this topic ad nauseam, but it’s never lacking in importance.

De-emphasizing the world of single-high coverage means you are losing a body near the line of scrimmage to fit the run in the box, and moving from four down linemen to three necessitates setting hard edges to force everything back in between the tackles. The Chargers are setting out to accomplish both, and while it’s not all the way there quite yet, you can see the beginning stages of what’s to come in Staley’s tenure as the team's head coach.

(Plus, I think I’ve carved out a small brand as a nerd for fitting the run. If you think I’m going to miss an opportunity to talk about run fits, never make such an error in judgment again.)

Everything begins between the B-gaps, from one guard to the other. This first clip gives a decent look at what I described above. The Las Vegas Raiders are attempting to run a strongside “lead” concept, where the five down linemen work away from the point of attack. The tight end and fullback will look to kick out the two most dangerous defenders at the point of attack, and the running back will work from the A-gap (off the hip of the center) out toward the edge.

Here, we start with the nose tackle, Forrest Merrill. You can see him executing his technique, striking through what’s called the “v of the neck” of the center, then mirroring his steps.

As the right guard works to double-team him, he moves into the next phase of the progression: stay engaged with the center, turn your shoulder into the double and try to wedge between. If you can’t win, fight until you fall and create trash in the middle. The double team was quick, but Merrill working through this progression with speed allowed him to spill the ball outside to his defensive backs in run support.

This is also a good clip for seeing how to set the “vertical” edge in the odd front — striking through a block with your outside foot up the field. When you lock your arms out and get separation, your hips will naturally pivot you back into a square position, but the blocker will be turned so that his back is facing the runner. Now, for the ball to bounce outside, the carrier has to go backward to get out of the box. Both Uchenna Nwosu and Joey Bosa set hard edges to keep the running back from working downhill.

This clip is a similar look to the first, but there are small intricacies you’d miss if we had only the broadcast copy. Here, Los Angeles has “eagled” the front, meaning the weakside defensive tackle shades outside of the guard and the nose shades outside of the center instead of playing head up. This is an easy way to get your nose better body presence in a gap when you anticipate an offense calling runs that look to work double teams.

Now, Merrill is striking through the “v” of the guard and fighting through the double from the center. But the key player here is Joe Gaziano, lined up in what’s called a “4 technique” — head up with the tackle. His job is not necessarily to play two true gaps, but to cancel them both by playing primary-to-secondary (you may hear a coach use terminology like “react-attack” in a press conference).

With the tackle working to his right, he’s mirroring steps and striking, fighting to close the B-gap by keeping the lineman’s back flat and hips square to the line of scrimmage. When Gaziano wins, he then needs to fight back to the C-gap to play the potential cutback. Whether he does it perfectly is less important than the intended result: keep the linebackers clean and present a flat surface to the running back.

This next clip is a good example of what the backside of a “weak eagle” front can do in the 3-4. The flow of the play is going away from Jerry Tillery, so he’s working to squeeze the space by running laterally and then “hooking” upfield. He’s able to match the movement of the offensive line and penetrate so well that he cuts off the fullback coming to kick out Bosa.

Also, Nasir Adderley obliterates Henry Ruggs III trying to block him, and I have a soft spot in my heart for punishing wide receivers who try to block.

Brandon Staley is far from the inventor of this defense or this style of fitting the run, so this has little to do with him and the Chargers specifically. However, I felt it important to highlight some of the things you’ll hear me mention in my posts and podcasts on PFF.

Growing up, I always heard about the 3-4 as the blitz-heavy defense, and the 4-3 as playing more static. To see coaches like Vic Fangio and Brandon Staley take the 3-4 and stop the run by playing with good technique and layering the defense (first, second, and third level) is the latest move in this never-ending chess match between defense and offense.

Dislike: Early-Down Offense in Pittsburgh

Plenty (and yet, still not enough) has been said about how Ben Roethlisberger’s atrophied arm talent places a hard ceiling on an offense loaded with skill position players.

New offensive coordinator Matt Canada came into Pittsburgh as the man expected to help fix the issues on the offensive line so the offense didn’t have to rely on Big Ben getting the ball out of his hands in less than 2.5 seconds each dropback.

Steelers play-drive success | 2021

| Offensive Success Rate (Rank) | Defensive Success Rate (Rank) |

Rate of Scoring Drives (Rank)

|

| 30% (30th) | 51% (2nd Highest) | 29% (27th) |

Through the first quarter of the season, this offense looks just as gummed up as it did in the second half of 2020 when it was clear Pittsburgh was not a real contender in spite of its record. On a down-to-down basis, Pittsburgh is flirting with being the worst offense in the league at staying on or ahead of schedule, currently 30th in success rate.

Too often, this offense finds itself on second- or third-and “obvious,” where the defense can play the pass first. Against Green Bay, a defense with little to no threat of a pass rush, Roethlisberger still had a difficult time working the ball where it needed to be in order to convert.

The Packers sat hard on shallow crossers and other in-breaking routes, forcing the ball outside the numbers where Ben struggled most. Seven of the 11 third downs Pittsburgh faced last Sunday came against single-high coverage, closing off the middle of the field.

Ben Roethlisberger targets

| Outside WR | Slot WR | Inline TE | Backfield |

| 24 | 3 | 4 | 7 |

When Mike Tomlin and his staff are self-scouting to find the fix for this offense, it can’t start with conversion downs. Expecting to win on third down in general is a tough ask, let alone with a QB actively holding the offense back.

The offense’s -0.107 expected points added per play on first down — which ranks seventh-worst in the NFL — is where Pittsburgh needs to find every edge that exists.

One thing is clear: The run game alone isn’t sufficient to survive for this unit. In Week 4, the Steelers had the sixth-lowest yards per carry mark on first down (3.4), which makes sense given the personnel.

Pittsburgh played out of 11 personnel on 80% of its total snaps, a rate that only the Los Angeles Rams eclipsed. Without the threat of creating extra gaps in the run game, an offense needs some kind of window dressing to make defenders honor more than just the gap they’re responsible for. In the spread world (which Pittsburgh lives in), that answer is the RPO.

Steelers first-down offense| Week 4

| Snaps | Offensive Grade | EPA/Play | |

| RPOs | 10 | 74.4 | .291 |

| Non-RPOs | 15 | 62.6 | -0.220 |

To no one's surprise, the Steelers’ first-down offense makes a seismic leap in its efficiency and performance when an RPO is involved. Not only does it fit the throws that Roethlisberger is best equipped to make, but it gets the ball in space and into loose coverage.

It’s not even a requirement that Canada asks his QB to make accurate throws on slants into tight windows. Most of the attempts against Green Bay were “access” throws, taking the yards the defense concedes by playing in off-coverage.

Leaning too heavily into any one thing can leave an offense in difficult territory, but the difference was staggering when Pittsburgh tried anything other than an RPO on early downs.

It may mean running a gimmick offense, but a gimmick is always better than an abject failure.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.