With three weeks of the 2021 NFL season complete, narratives are beginning to take hold.

A healthy Cleveland Browns team is knocking on the door of the top-tier squads in the NFL, the Dallas Cowboys have a championship-ready offense and the Los Angeles Rams stand alone atop the hierarchy of contention for the moment.

On the other end, the New York Jets are two years away from being two years away, the San Francisco 49ers and the Washington Football Team are experiencing a massive regression, and the Pittsburgh Steelers are suffering through what we can only hope is quarterback Ben Roethlisberger’s farewell tour.

In all of last Sunday’s action, here are the best and worst events between the lines.

Click here for more PFF tools:

Rankings & Projections | WR/CB Matchup Chart | NFL & NCAA Betting Dashboards | NFL Player Props tool | NFL & NCAA Power Rankings

Like: The Evolution of “Shanny-Ball” Runs by Matt LaFleur

The mark of a scheme’s staying power is found in the ability to adapt it over time. In each generation of football, a dominant coach watches his offices become revolving doors for the best and brightest minds in the sport.

However, the franchises and coaches that believe one can enjoy the successes of another regime by copying and pasting another's approach are doomed to fall short. Proximity to and familiarity with greatness alone hasn’t won a football game yet.

We’ve seen the young cadre of elite play callers take the framework of Mike and Kyle Shanahan’s two-back/two-tight end zone offense and create variations unique to the personnel, philosophy and personality of the coach and franchise.

Sean McVay burned so hot early in his tenure in Los Angeles, and Aaron Rodgers has an individual gravity in Green Bay, making it easy to bypass what Matt LaFleur has done in the face of the greatness of his peers and his signal-caller.

On Sunday Night, LaFleur faced off against one of the architects of the offense he grew up under, and what “Shanny-ball” looks like to him now.

The first and biggest difference comes in personnel usage. Kyle Shanahan is still true to the two-back offense his father used in the '80s and '90s with the Denver Broncos, even in an era that incentivizes offenses to spread the formation out. On 25% of the snaps in Week 3, the San Francisco 49ers had two backs on the field.

LaFleur is not as married to playing with heavier personnel — only one of his offense’s snaps in Levi’s Stadium had two backs on the field, and that two-back formation didn’t look anything like the I formation.

I talked about it in last week's likes and dislikes — offenses can use one personnel grouping to make the formations more typically seen in others.

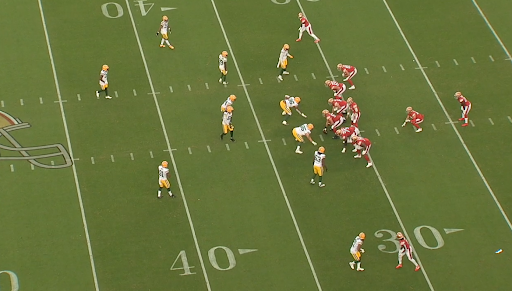

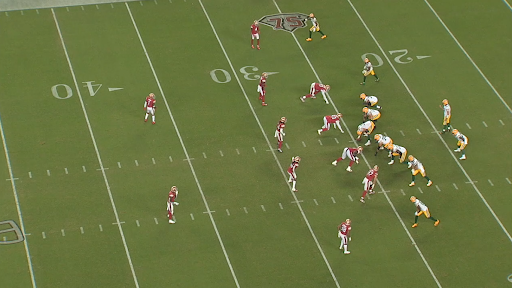

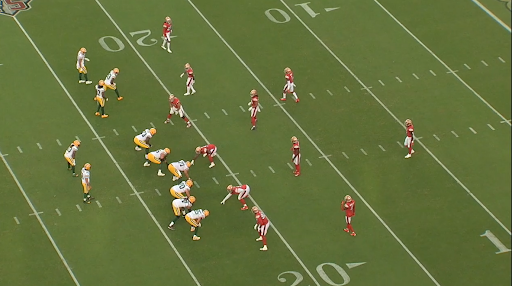

This is what 21 personnel looked like for Shanahan:

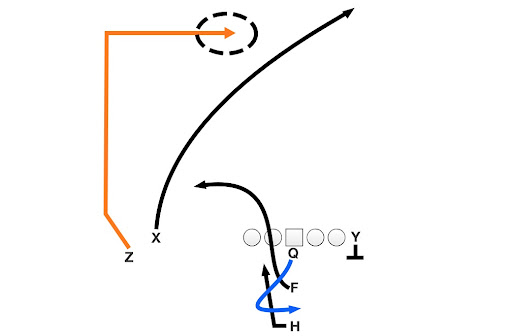

And this is what the lone snap in 21 looked like for LaFleur:

Beyond that, personnel multiplicity is a much larger concern for Shanahan than LaFleur. The 49ers doubled up the Packers' three personnel groupings used throughout the course of the game, as 58 of the 59 snaps Green Bay had in the game were in 11 and 12 personnel.

The lack of two-back sets in this scheme, which is based on zone blocking principles and split flow (which I’ve talked about at length before), makes it harder to keep linebackers from flowing downhill to fit their gaps.

The fullbacks in Shanahan’s offense keep linebackers honest by splitting across the formation and kicking out the backside defender, opening a cutback lane. If the inside linebackers flow hard, the running back can bend back away from them into the first open window.

Without the traditional fullback, how can an offense initiate split flow on zone action?

The added element of the option game out of the spread is the way LaFleur can stay true to the two-back elements of the scheme. The innovation of the last era was to use the quarterback's legs as the split action in the read-option game. Today, the screen game can create the same kinds of issues without the volatile investment of running your quarterback into harm's way.

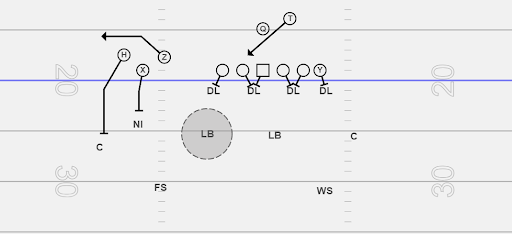

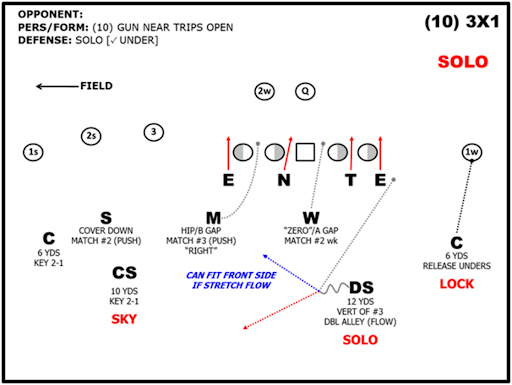

Green Bay tags bubble screens to wide receiver Davante Adams on the front side of the zone run in 11 personnel. By using 3-by-1 formations (three receivers to one side, one opposite), the linebacker inside of the No. 3 receiver now has dual responsibilities: against the run, he needs to fit his gap; and against the pass, he has to play any underneath route from inside-out.

With Adams in the slot, linebacker Fred Warner wants to midpoint his responsibilities in case Rodgers spins it out to the screen, so he can pursue from a good angle. This creates enough space and time for the offensive line to work double teams up the field, and running back Aaron Jones has a clean picture to work off.

This extension of the run game keeps the integrity of split zone’s design — the bubble screen holds the backer, the tight end kicks out on the backside edge and the double teams create a downhill push. Voila! LaFleur has remade a two-back run in the spread offense, helping to push Shanahan’s scheme into the future.

Dislike: Coverage Hurting the Pass Rush in Washington

It is with a heavy heart that I tally a point for PFF’s Eric Eager in the coverage versus pass rush debate.

There should not be a world that exists where generating 29(!!) pressures on a quarterback over the course of a game results in surrendering a 75% completion rate, 23 first downs converted, a 128.9 passer rating, only one turnover worthy play and zero sacks.

Nothing has changed up front for Washington — the plan of employing DaRon Payne, Jonathan Allen, Montez Sweat and Chase Young as your top four rushers is just as sound now as it was when this defense leaped forward in 2020. As a team, the pass rush had eight hits and 21 hurries on Buffalo Bills quarterback Josh Allen, and only one pressure was from an unblocked rusher. Sunday’s pass rush wasn’t about scheming up free runners and forcing protection breakdowns, they just kicked Buffalo’s [redacted] up front.

Washington is hurting the most where the regression from last year to now is becoming more glaring: standing up in coverage on the perimeter. The alarm bells should have rung out much louder following the Thursday Night game against the New York Giants, but I had just chalked it up to the athletic receiving corps quarterback Daniel Jones has to work with.

Buffalo has an even better collection of route-runners, of course, but being tuned up in back-to-back weeks is evidence of a dangerous trend for defensive coordinator Jack Del Rio. There would be ample space to hold Del Rio accountable, too, if he were only asking his defensive backs to play man-to-man coverage, but he’s been consistent in mixing up his schemes between this year and last.

| WFT Pass Defense Production | Dropbacks | Pressure Rate | EPA/Play Allowed | Pass-Rush Grade | Coverage Grade |

| vs. Buffalo | 48 | 48% | .353 | 79.4 | 52.7 |

Unfortunately, there’s nothing to draw up on a whiteboard to protect defensive backs who are easy to attack in man, Cover 3 and Quarters. In fact, this secondary has done its worst work in Cover 4 — a scheme designed to generate a coverage advantage (three defenders for two route runners) — with an EPA per play number above .500 through the first three games.

Watching the explosive throws Josh Allen had last Sunday illustrates the lack of trust this defense has in its cornerbacks' ability to handle their matchups. In the first clip, we start by giving credit where it's due to Brian Daboll for calling a Quarters “beater.” This is called “Mills” — a combination of a deep in-breaking route and a post over the top.

Stefon Diggs runs an excellent post route, leaning into the corner’s area before breaking back across the safety’s face to force both defensive backs to carry him through the middle of the field. The ball is thrown to the deep curl beneath the post, and my issue is not with those defensive backs for doing what they’ve been taught to do.

However, because Del Rio doesn’t believe his corners can win one on one, the safety on the backside of the formation is helping in double coverage on the single receiver, Emmanuel Sanders. Having a Quarters safety push out toward the sideline means there’s less body presence near the middle of the field, which opens space for throws like we just watched.

If Washington were better equipped to play single coverage, that backside safety could now “poach” — hunt for the deepest in-breaking route to cross the field. That would give the frontside safety some relief on Diggs’ post and allow the corner covering the Mills concept to drive down on the curl. Poaching is something more commonly seen in trips coverages, but safeties in Quarters can work frontside when their receiving threat can’t immediately release vertically.

This issue bites them again in this game for an explosive play, on a concept called “dagger,” where two receivers are running deep in-breaking routes. One will operate as a clearout, and the other is meant to sit in the hole.

Slot receiver Cole Beasley gets some poor intel on his route because the safety on his side is climbing deep as though he’s covering the middle of the field. Beasley bends his route into a deep in (called a Dig) and settles in the hole in the zone. Again, this completion is less of the fault of the front side of the coverage — with the backside safety widening out to help on the single receiver, there’s no one to drive down on the crossing route, asking linebackers to do the impossible task of covering a route being run at a depth they cannot see.

If Washington can’t find a way to close open window throws like this later in the season, it will be right back to picking in the top 10 of the NFL draft.

Dislike: Five-Man Protection, In General

I’m kinda floored that this clip is receiving so much oxygen for something that feels straightforward

1. The protection needs to be set so the QB has vision on who he’s hot off of. Center’s fault.

2. Even if Peters got the cleanest dual read, he had no shot because he’s COOKED! https://t.co/DGJgZPs0ke

— Diante Lee (@PFF_DLee) September 29, 2021

I have reached my end with five-man pass protection schemes.

Someday, an offensive coach will wave the white flag on second- or third-and-long and submit to the fact that defenses have just about cracked the code on how to bust a protection.

Maybe I’m the one who’s wrong, and offenses just had a rough go for the past couple of weeks. I understand that releasing the running back into a route is an important piece of spacing the field.

Maybe there’s some hidden trend in the quality of centers being drafted and developed to understand the proper ways to set a protection. We’re entering an era of an entirely new batch of quarterbacks, and the biggest growing pains come from learning how to identify where pressure can come from.

Whatever the reasons may be doesn’t matter much — defenses are finding success in punishing empty protections with pressure packages, and some quarterbacks have been eating a lot of turf because of it.

In Week 3, NFL defenses had a significant 9% sack rate when blitzing five-man protections on pure dropback passes (no play action, no RPO) and generated an unblocked pass rusher on 22% of those snaps. Every passing concept comes with a hot throw, but if a defense can trigger a scramble, sack or hot throw by getting unabated rushers on the quarterback once every five pressures, there's reason to have some concerns about the efficacy of the scheme.

| 5-Man Protection vs. Blitz, Pure Dropback | Dropbacks | Pressure Rate | Sack Rate | Unblocked Pressure Rate |

| NFL Totals, Week 3 | 125 | 53% | 9% | 22% |

For added context, there were 791 “pure” dropbacks in five-man passing protection last Sunday. Of the 51 sacks suffered in the protection scheme overall, 34% came during a blitz. Of the 44 total unblocked pressures, 61% came from blitzes.

Even if the pressure isn’t being converted into a sack, it hasn’t come at the cost of being punished by the arm of the quarterback. The Week 3 NFL average of 6.8 yards per attempt in five-man protection holds steady when only looking at blitzes, and only five teams passed the ball beyond the line to gain more than half the time when being blitzed.

I wanted to take a look at a few of the 27 unblocked pressures in these situations to see if there were any common schematic trends defensively or breakdowns on offense:

This first look comes from the Tennessee Titans in their win against the Indianapolis Colts. The Colts are in an empty set, and the Titans are bringing the weakside linebacker in a fire zone (three deep, three under zone coverage). The protection is sliding correctly: You want to send three pass protectors in the direction of the most likely player to blitz, and the empty look puts the slot corner too far out to pressure. If he did, the quarterback is responsible to throw “hot” off him.

The pressure track works out like a twist stunt — the defensive tackle presses into the guard without crossing his face, engaging both him and the guard. The linebacker loops into the opposite A-gap, and the guard executes properly by turning back to pick up the defensive tackle pressing into his inside shoulder.

(This is likely a coaching point for this blitz against empty. The hope for the defense is that the line slides toward the three-receiver side, and the linebacker rushes the B-gap between the guard and tackle. If the line slides toward the pressure, loop to the opposite gap where there’s space to fit into. This way, there’s more coming from one side than the offense has to block.)

The breakdown happens with the center, who has no vision on the looping linebacker because his head is buried into the defensive tackle. Had he seen the movement, the guard would turn back into the tackle and the center would pick up the linebacker, and Carson Wentz would have an escape route or extra time to work through the progression.

In this clip, the Arizona Cardinals are bluffing Cover 0 by walking six defenders up to the line of scrimmage. Because each lineman is covered up, the line goes into a “big-on-big” protection, meaning these five will pick up the most dangerous threats from inside out. The protection call was correct in this scenario: Arizona is running a five-man pressure, but the presentation creates the breakdown.

The right guard and tackle are covered, and linebacker Isaiah Simmons is walked up outside of them. In this case, the guard and tackle have to pick up whichever two of the three that rush (and if all three rush, the quarterback is hot off the third). The guard and tackle don’t get enough depth in their pass sets to sort out the pressure track, allowing edge rusher Markus Golden to pick the tackle and keep Simmons free off the edge.

Presentation makes the pressure work in this next clip out of Tennessee, with three of the four rushers set away from the back. Just like Arizona manufactured a big-on-big look against Jacksonville, this front forces the offensive line to four-man slide over to the tilted side of the front.

Again, poor vision and trust by the guard open the door for the blitzing linebacker. With the slanting linemen coming back across the slide, the guard should engage and pass his rusher off to the center, who is passing his rusher off the guard behind him. If this were executed properly, there’s no air space to rush into.

(This is another excellent design, this time to guarantee that the back doesn’t stay in to help. Because the back is looping toward the sliding protection, he gets his indicator to release on his route, meaning he’s not home to help on potential busts in the protection like this.)

Like: A Rookie Completing the Cleveland Browns’ Defense?

Of course, we want to contextualize any game against the Chicago Bears as just that: a game against the Chicago Bears. However, in games like those against clearly inferior opponents, you can get a clear idea of what a defense is at its core.

The Cleveland Browns‘ defense, led by coordinator Joe Woods, wants to play and win every one-on-one matchup possible. Woods assisted in coaching one of the best passing defenses in NFL history with the Super Bowl-winning Denver Broncos and was the passing game coordinator for the 2019 NFC champion San Francisco 49ers. What those two stops have in common are defenses led by a relentless pass rush and an ability to live in one-on-one coverages on the perimeter, regardless of the coverage called.

The defense lives in the three coverage structures we see most often in the NFL today: Cover 3, Cover 4 and Cover 1 (40%, 33% and 10%, respectively).

Pass rush won the day against the Bears, but holding an offense under 100 yards is a feat and a half — something a team can’t do with its front four alone. Knowing the defensive structure and trying to toggle evenly between these worlds in coverage is a matter of personnel on the back end, so I wanted to look at how Cleveland positions its players based on the coverage called.

| Cover 3 Roles | Top Player By Snaps, 2021 Season to Date |

| Middle of Field Safety | John Johnson III |

| Box Safety | Ronnie Harrison |

| Inside Linebacker 1 | Malcolm Smith |

| Inside Linebacker 2 | Mack Wilson |

| Slot Defender | Troy Hill |

Troy Hill and John Johnson III, two offseason signings, got put right to work in covering up some of the old holes in this roster. When Woods calls for Cover 3, He wants Johnson playing the post (middle of field safety) and Hill in the slot as his nickel corner — the role he used to serve under then-Los Angeles Rams defensive coordinator Brandon Staley. Ronnie Harrison rolls down as the box safety to account for tight ends and running backs with linebacker Malcolm Smith and budding rookie Jeremiah Owusu-Koramoah, who fits Woods’ mantra from top to bottom — a do-everything linebacker who can erase mismatches and help against the run.

| Quarters Roles | Top Player By Snaps, 2021 |

| Seam Defender 1 | John Johnson III |

| Seam Defender 2 | Ronnie Harrison |

| Inside Linebacker 1 | Malcolm Smith |

| Inside Linebacker 2 | Jeremiah Owusu-Koramoah |

| Slot Defender | Troy Hill |

Where Owusu-Koramoah earns his draft positioning is in how well he can adjust his play to the coverage call. In Quarters, Harrison rolls back to protect the seams of the defense with Johnson, meaning Owusu-Koramoah has to stretch his zone responsibility out from the box to the flats. The snaps he logged as a hybrid second-level defender at Notre Dame served him well for this, and he’s been productive whether the middle of the field is closed or open.

When it’s time to play man coverage, that’s where the value of a player like Owusu-Koramoah skyrockets in the NFL. His athletic profile allows Woods the ability to truly hunt for his best matchups at all times. The rookie can be used as a coverage player to erase tight ends or running backs, or as a pass-rusher in the Browns' blitzing schemes to free up one of their elite pass-rushers.

| Jeremiah Owusu-Koramoah Performance | Grade (Snaps) |

| Run Defense | 86.3 (19) |

| Pass Rush | 71.8 (7) |

| Coverage | 76.2 (29) |

It’s rare for a rookie defender, especially a linebacker, to come in and be a skeleton key for all of the different schemes a coordinator wants to run. However, because Owusu-Koramoah is protected in both directions (the secondary and the defensive line), Woods gets to use him however he pleases.

| Jeremiah Owusu-Koramoah by Coverage Scheme | Defensive Grade |

| Cover 3 | 87.9 |

| Quarters | 67.1 |

| Cover 1 | 90.2 |

We should all be getting familiar with Owusu-Koramoah now, because he can certainly become the next superstar player at this position.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.