Football is a wonderful game, a gift that provides data and narratives every single week, both at the NFL and NCAA levels.

While we've answered many questions about this game, some remain a mystery to me. I’m firmly in the “pass the damn ball” camp, and while there are obvious exceptions, I’m on the team of people who believe that the running game is largely a product of the offensive line and scheme and should be deployed less.

Click here for more PFF tools:

Rankings & Projections | WR/CB Matchup Chart | NFL & NCAA Betting Dashboards | NFL Player Props tool | NFL & NCAA Power Rankings

However, teams still run the ball … a lot. And the more I talk to individuals within the league, the value of the run continues to come up. However, the data is pretty clear: In most cases, running the ball is less efficient and less successful than throwing it, and this result is pretty stable with respect to the other players on the team. So, why do teams still run the ball so much?

In another attempt to examine this problem, I looked into our play-by-play grade data for run-blockers and pass-blockers to see how “fragile” the running and passing games are to negative plays by blockers.

Editor's note: You can look at this article for information on how PFF grades run-blockers and this article for how PFF grades pass-blockers.

In the run game, blockers earn a grade from -2 to 2 in increments of 0.5 based on how well they performed their assignment. In this article, we’ll consider a grade of -0.5 or worse a “loss” for the run-blocker. In pass protection, positive grades are not given out (at least initially, though they are after normalization), so 0 is a win, and less than 0 is a loss.

The Running Game

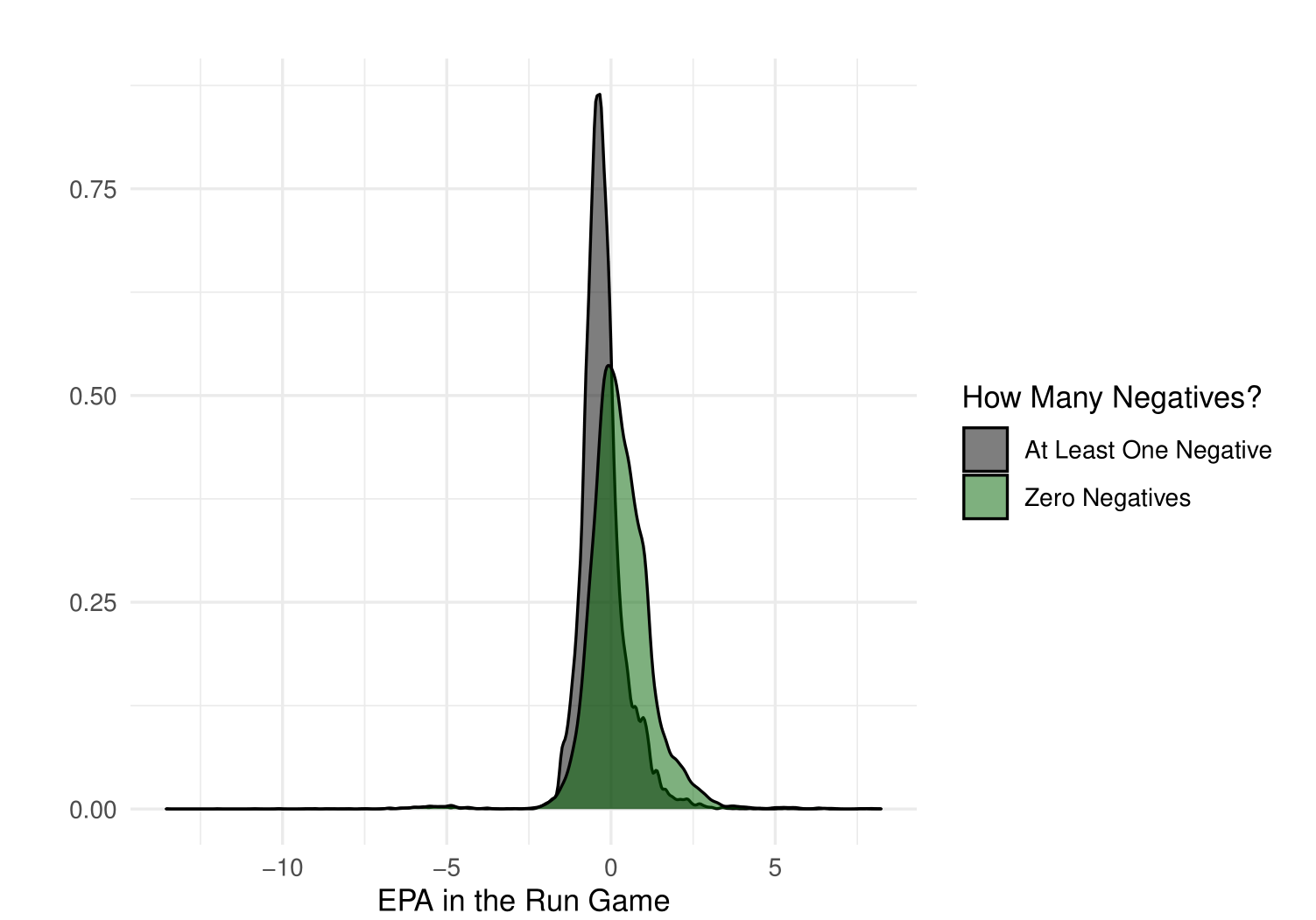

To study the effects of the first negatively graded block, I looked at the differences in expected points added (EPA) and success rate (whether a play had EPA > 0) when there were zero negatively graded blocks and one or more negatively graded blocks. For run plays on early downs in the first three quarters of close (within 16 points) games, the differences were drastic:

| # of Negatively-Graded Blocks | Success Rate in the Running Game | EPA in the Running Game | Percentage of Such Plays |

| 0 | 60.2% | 0.27 | 34.9% |

| 1 or more | 25.7% | -0.27 | 65.1% |

Offensive success in the running game with 0 negatively graded blocks and 1 or more negatively graded blocks. Early-down run plays in the first three quarters of close (within 16 points) contests and no two-minute drill. 2017-2021 data.

This paints a really explicit picture of what a “perfectly blocked-up” running play means to an NFL team. For all plays, the success rate for run plays is well under 50%, and they generate less than 0 EPA. If a run play is perfectly blocked up (using PFF grades), the running game itself is more efficient than the most efficient offenses in the NFL.

The figure above shows the effect of perfectly blocked running plays — they shift the distribution of outcomes to the right, and drastically so.

It’s extremely difficult for a perfectly blocked running play to be a negative play and extremely hard for a play with even one negatively graded blocker to produce positive results.

The Passing Game

© 2026 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2026 PFF - all rights reserved.