We are in full-on offseason-abyss mode right now. With the 2020 NFL Draft almost a month in the rearview mirror and free agency in the distant past, it’s time to talk about one of the remaining points of contention among players, teams, fans and media members — what to do about quarterbacks like Dak Prescott, Patrick Mahomes and eventually Deshaun Watson.

Prescott has been the subject of a number of articles from our group over the past 12 or so months. First, we were skeptical of the idea that he was worth a record-setting deal and contrasted his situation with that of Russell Wilson’s in Seattle. And after Dak was the second-most valuable player in the 2019 regular season (behind Wilson), Dallas decided to put the franchise tag on him, which is where the standstill remains.

Mahomes followed up his (deserved) 2018 MVP award by taking the Kansas City Chiefs to their first Super Bowl in 50 years and accumulating the most wins above replacement of any player over the last two years. Entering Year 4, Mahomes is eligible to sign a new deal, and given his stature as the league’s next great quarterback, he should set the market for the foreseeable future.

Watson is an interesting case in that he has taken the Houston Texans to consecutive 10-win, division-title seasons despite some real flaws on behalf of him (specifically his pressure rate) and Houston’s front office. The first-round pick out of Clemson has been the league’s 10th-most-valuable player over the last two seasons, and the 15th-most-valuable player if you include his injury-shortened 2017 season. On the one hand, it might benefit Watson to wait another year to sign an extension, although, on the other, it is tough to see him repeating what he has done thus far without DeAndre Hopkins, who was his best weapon in Houston.

[Editor’s Note: PFF’s advanced statistics and player grades are powered by AWS machine learning capabilities.]

The Dallas Cowboys, Houston Texans and Kansas City Chiefs have been among the biggest beneficiaries of the much-understood advantage of hitting on a quarterback who is playing on a rookie deal. Of the top eight teams in the NFL in terms of wins above replacement generated per dollar spent at the quarterback position in 2019, six were teams who started a quarterback on a rookie deal for the majority of the season. The seventh team was Miami, who combined a quarterback on a rookie deal (Josh Rosen) with a cheap veteran (Ryan Fitzpatrick).

The top four teams when looking at it this way were, in order: Dallas, Baltimore, Kansas City and Houston. Seattle (seventh) was the only team in the top-eight whose quarterback had a top-end, veteran deal, while the bottom six teams in that ranking (Pittsburgh, Carolina, Washington, Cincinnati, the New York Giants and Detroit) all had veteran quarterbacks making a substantial amount of money miss a significant part of the year due to injury or ineffectiveness.

This, again, begs the obvious question. Is there actually a benefit to paying quarterbacks top-end, veteran deals in lieu of going back into the draft or free agency for a more inexpensive option? Here we look at the problem through a few lenses.

Does Spending More on Your Quarterback Correlate with Winning?

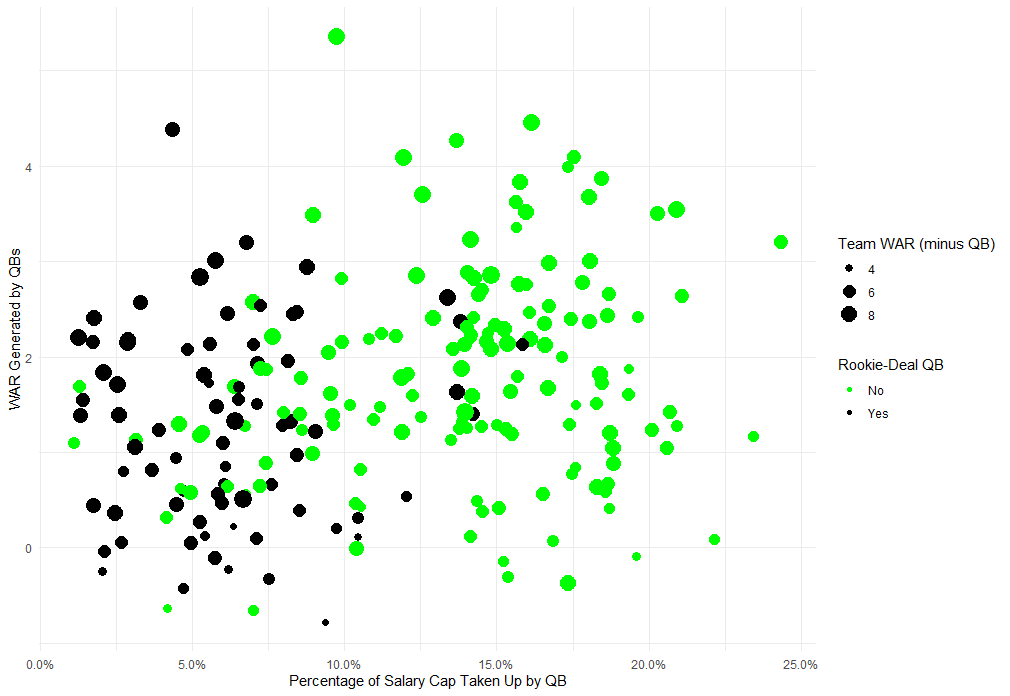

In short, yes. The more of the cap that is spent on the quarterback, the better. Using Over the Cap salary data as well as our PFF Wins Above Replacement metric, it’s plain that spending a higher percentage of the cap on a quarterback does correlate with better quarterback performance.

This makes sense. If a team pays a quarterback more, it’s likely because he was good enough to deserve a bigger contract and performed well relative to expectations thereafter. It’s noisy, though (with the percentage of the cap explaining just 7% of the variance in QB WAR), and as you can see, quarterbacks who outperformed their expectation generally played for teams that saw the rest of its roster earn more WAR than those that underperformed expectations (signified with the bigger dots above).

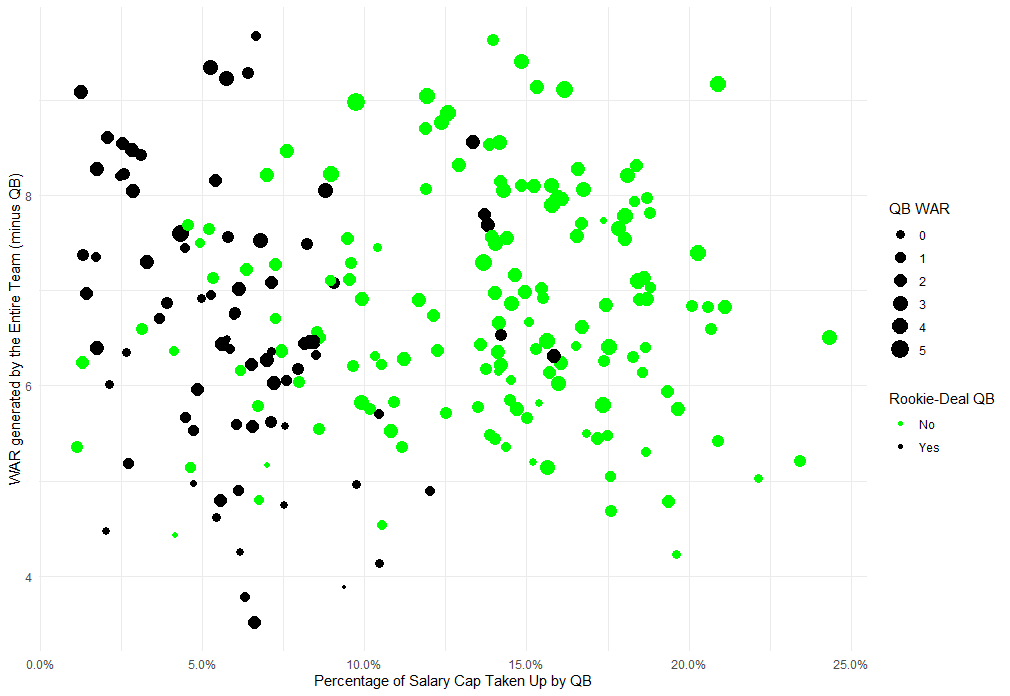

Turning this plot the other way:

This relationship is basically flat, with the amount of money spent on the quarterback having little effect globally on how much value is produced by the rest of the roster.

The two graphs above show that the problem is not as simple as looking at quarterbacks, as there are clearly two clusters within both of these graphs: one representing teams with quarterbacks on a rookie deal and one with quarterbacks on a top-end, veteran deal.

The trend is less positive within both of these clusters, with both WAR generated by the quarterback (first graph) and WAR generated by the rest of the team (second graph) increasingly weak in the proportion of total salary allocated to the quarterback position. In both clusters of both graphs, the decrease in WAR generated by one part of the team is accompanied by a decrease in WAR generated by the other. This begs the next question.

Exclusive content for premium subscribers

WANT TO KEEP READING?

Dominate Fantasy Football & Betting with AI-Powered Data & Tools Trusted By All 32 Teams

Already have a subscription? Log in

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.