There was a time in football history when schematic changes occurred at a snail's pace. Before the internet took over, coaches had to have film physically delivered to them. I’ve heard stories about young graduate assistants driving to the local airport to pick up reels of film on their team's next opponent. The idea of having to splice together film reels gives me anxiety as an entitled millennial.

Those days are long gone. Film is passed around with ease, and everyone gets a chance to inhale all the “Spider 2 Y Banana” they want. The game changes so rapidly now that by the time we think we see a trend, 31 other teams are preparing or have an answer for it.

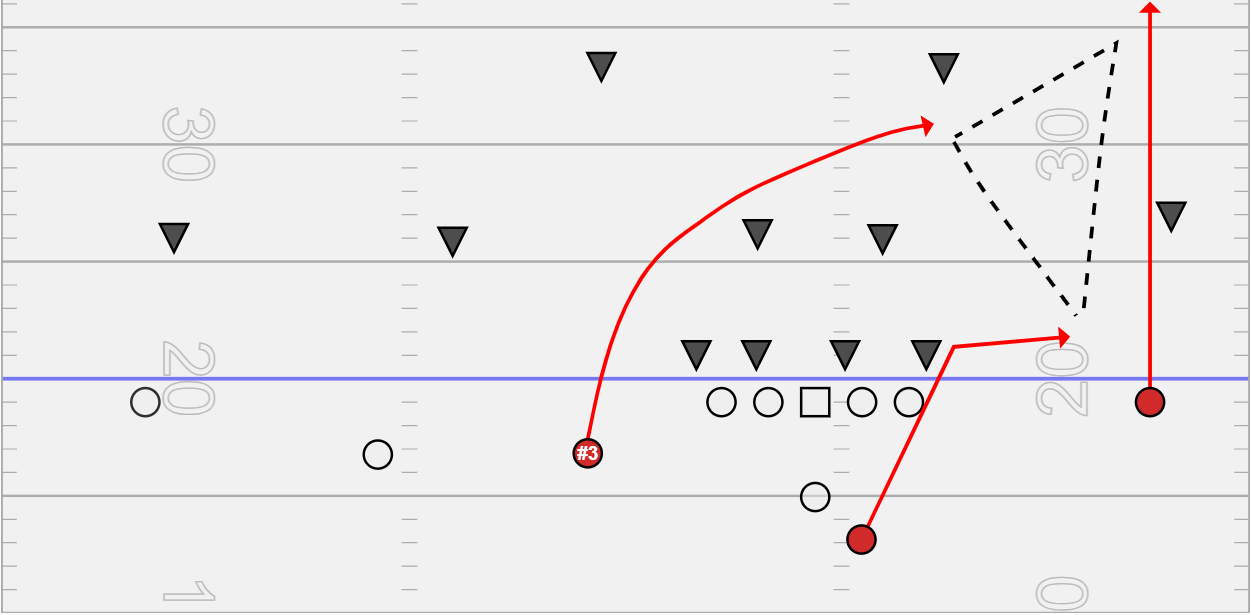

The Kansas City Chiefs have fielded the prototypical NFL offense over the past couple of seasons, and one of the unit's most common schematic advantages is using Tyreek Hill or Travis Kelce at the No. 3 position in trips and running them across the field to create a weakside passing triangle.

Weakside Passing Triangle

In 2013, the first year PFF has data on this, the top 10 players who lined up at the No. 3 position in trips — ranked by snaps — were all tight ends. Tight ends made up 55% of the snaps league-wide from the No. 3 position. In 2020, that flipped. Receivers accounted for 55% of those snaps. That number would increase if we just collectively decided that Mike Gesicki, who aligns as a true tight end on only 20% of his snaps and played the second-most total snaps at the No. 3 position in 2020, was a receiver — but I digress.

One reason the Chiefs and so many other teams love to put a speed player at the No. 3 position rather than an inline tight end is because of the matchup they can get on a linebacker. Overall, teams still go into trips with an inline tight end as the No. 3 because they can affect the run game. But when teams want to throw, splitting that player out in the open is beneficial.

In the 2019 regular season, the Chiefs targeted their No. 3 receiver the second-most number of times in the league and then went on to win the Superbowl. When a team wins a lot of games, people are going to go the extra mile to figure out what they are doing and how to stop it. Targets to that receiver in trips were down a bit for the Chiefs in 2020.

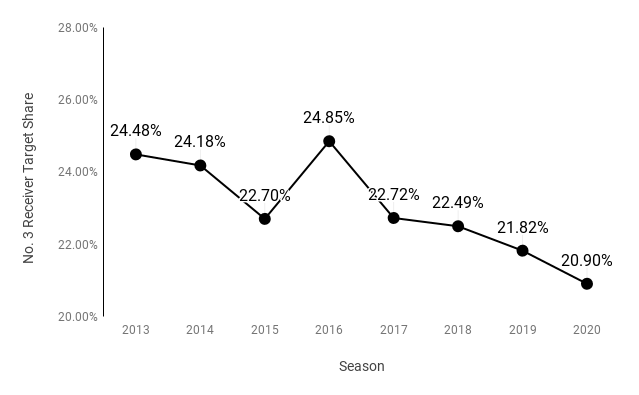

In fact, league-wide targets to that receiver have actually been trending down. I originally thought I was going to be writing an offensive piece about this concept, but I came away realizing that defenses have already become wise to the offensive funny business.

Target Share to No. 3 Receivers Has Fallen

Teams are going into trips sets more often but are finding it increasingly difficult to get the ball to the No. 3 receiver when he’s lined up in the slot. Just about one-quarter of throws were to the No. 3 receiver in trips open formations in 2016, the highest of any year since 2013, when PFF began tracking the data. By 2020, that fell to 21%, the lowest season rate in the data set.

One of the biggest differences is what routes these targeted receivers were running in 2016 compared to 2020. In 2016, 32% of targeted routes to the No. 3 receiver were on in-breaking or crossing routes — routes that had the receiver cross the offensive center. In 2020, that figure was a mere 24%. Offenses love that weakside triangle, but defenses have already adapted to take it away.

One of the big storylines going into Superbowl 55 was how the Tampa Bay Buccaneers would deal with Tyreek Hill at the No. 3 position, a facet of the Chiefs' offense that Tampa Bay decidedly did not deal with in the teams' earlier regular-season matchup. For most of the game, the Bucs played in two-high safety coverages where the backside safety had eyes on Hill, looking for him to cross the field. It worked.

In the previous year's Superbowl, the 49ers also had their weakside safety looking for the Hill crossing route for most of the game. Most defenses want to deal with trips formations like this, in a “weak-rotated” coverage. This is how the New Orleans Saints, the most efficient pass coverage team in the 2020 season against “3 open” formations outside of the red zone, did it.

Earlier this offseason, I wrote that teams played fewer true one-high pre-snap looks in 2020 than we have seen in many years. In these “strong-rotated” coverages, there is no player lined up in the area where the No. 3's crossing route is heading. That’s not a good business model, and we can see the Cleveland Browns get toasted on a Hill crossing route in their divisional-round playoff game:

In man coverage, most team's rules state that the player covering the No. 3 receiver is to align slightly outside of the receiver. The reasoning is that the defender's help is inside: In the Browns example, the Mike linebacker is the low-help player and the safety is the high-help player. The man coverage defender tries to funnel the receiver into his help. The problem is that players like Hill in the slot have made it almost impossible with their speed.

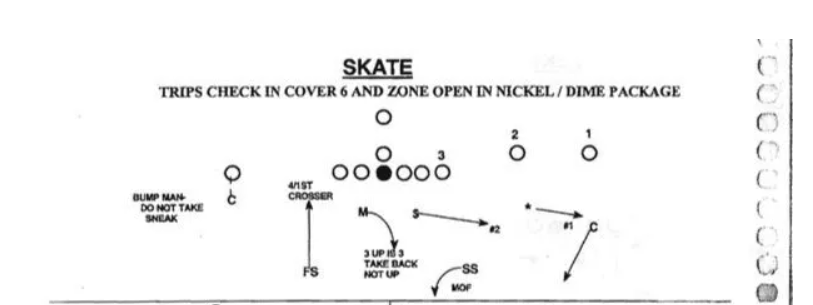

If a team is going to align as if it's already rotated into a one-high shell but instead plays Cover 3, the problems can be mitigated by “flooding the coverage” and having a weakside player try to catch that No. 3 receiver flying across the field from low to high.

The weakside “hook” defender plays a technique that is often called “3 up is 3” and looks to the strongside to pick up any crossing routes. The problem is that this hook player, in a look that is already rotated, is going to usually be a linebacker. It’s not a matchup that most teams can afford to live in unless they have a special player at that position.

Bobby Wagner is one of the best all-time at this specific technique, but most teams don’t have Bobby Wagner.

In fact, we saw in this past year's national championship game between Alabama and Ohio State what happens when the matchup doesn’t fall in the defense's favor.

absolutely howling at ohio state’s #32 struggling to keep up with devonta pic.twitter.com/Ehj3TkE8vB

— mike taddow (@MikeTaddow) January 12, 2021

With a tight end lined up inline in a three-point stance, this coverage has a better chance to work. But that's not the case with the speedier receiver that teams are splitting out in 2020.

The Saints rarely showed this look last season. Either they played quarters and had the weak safety look inside, or they played a flooded Cover 3 but used the weak safety to play the “3 up is 3” technique from top-down rather than bottom-up like a linebacker.

Whether it’s the quarters look or the weakside rotated Cover 3, you end up with the same advantage against the crossing route: letting the route come to him rather than the player chasing from bad leverage. The Saints showed one-high pre-snap and then ultimately played a one-high coverage post-snap only 24% of the time against trips last season. Even when they were playing Cover 1 and Cover 3, they still rotated down into it, usually with the weak safety.

This is how most teams will play defense in the coming years, but the Pittsburgh Steelers, the fourth-most efficient defense against trips, showed us that there is still room for strongside rotations to defeat the deep crossing route to the weakside.

Instead of rolling the weakside safety down, they rolled the strongside safety down. On paper, this would open up the hole on the field where the offenses want to run their deep crossing route, but the Steelers messed with their safety technique to gain back the advantage.

Instead of the weak safety flying to the middle of the field in a Cover 1 defense, he would sit and chill in his spot as he read out the patterns in front of him and the quarterback's eyes. By sitting in his spot, he dissuaded the quarterback from throwing the isolated route on the backside and then the deep crossing route just by his positioning.

There are certainly going to be other areas where teams can attack the Steelers when they do this, but Pittsburgh is banking on the fact that it can get to the quarterback while he goes through the process of eliminating untargetable routes.

Being already rotated strong pre-snap and playing Cover 1, as we saw earlier in the Hill catch versus the Browns, is probably the hardest way to stop these routes. The defender who doesn’t have any man-to-man coverage responsibilities — in the Browns' case, the Mike linebacker — was never going to turn and run with Hill. The Browns' slot defender is outside leverage because he thinks his help is inside. Those are very common Cover 1 rules. As long as there is a free player or “rat in the hole,” slot corners will play outside leverage.

The master, Bill Belichick, went against the grain in the Patriots' matchup against the Chiefs in 2020. After a few catches by Hill early in the game, Belichick had Stephon Gilmore flip to an inside shade alignment on the snap and force Hill to keep gaining depth on his pattern, which essentially funneled him to the safety.

You can open yourself up to other routes being run by the offense, but if there’s a cliché we always stick to Bill Belichick, it’s that he tries his best to take away your best. This is a great example.

Stopping this route from this position has become one of the modern defense's top priorities, but it does seem as though they’ve been doing a good job eliminating targets overall throughout the past few seasons. As weakside rotated zone coverages — quarters and weak-rotation Cover 3 — become a bigger part of the NFL, defenses will naturally have answers to “speed at No. 3.” The onus shifts back to the offense to find different ways to get its slot receiver looks and catches.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.