At this point, it’s common knowledge that rookie quarterbacks will generally play worse than their second-year counterparts. This effect is often called the second-year jump or second-year breakout and is reflected in this year’s MVP odds — Justin Herbert (+1,800), Tua Tagovailoa (+4,000) and Joe Burrow (+4,000) are considered much more likely to have an elite season than the rookie quarterbacks, among which Trevor Lawrence und Trey Lance (+10,000 resp.) have the shortest odds.

We studied the existence of this effect earlier and learned that its present for almost every position in the NFL, so now we want to study the effect for quarterbacks in more depth, try to learn what drives it and whether we can predict it for this year’s sophomore quarterbacks.

Subscribe to

The second-year jump is unique

The second-year jump is interesting because it’s the only development phase in which most quarterbacks seem to take a step forward in their overall quality of play.

To illustrate that, we look at all quarterbacks with at least 2,000 career dropbacks (50-65 career starts) to remove those so bad that they immediately lost the starting job from the sample.

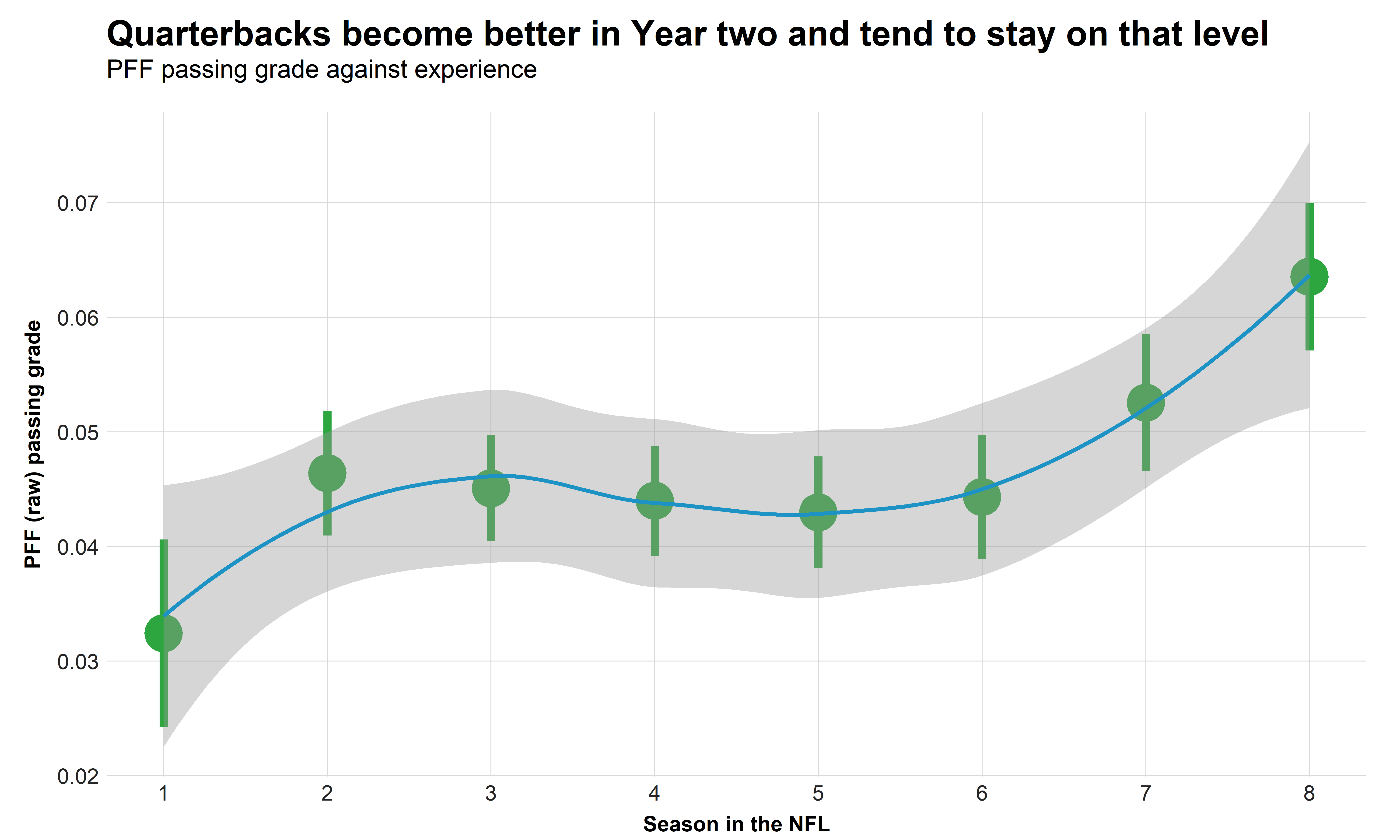

The following chart shows the average performance of these quarterbacks against their experience.

We can see that, on average, the jump between Year 1 and Year 2 is the only significant change for most quarterbacks. Note that we have conditioned on quarterbacks playing at least four years in the NFL, so it’s not a surprise that the curve goes up beyond those years. This is survivorship bias, as only the quarterbacks who further develop play for such a long time.

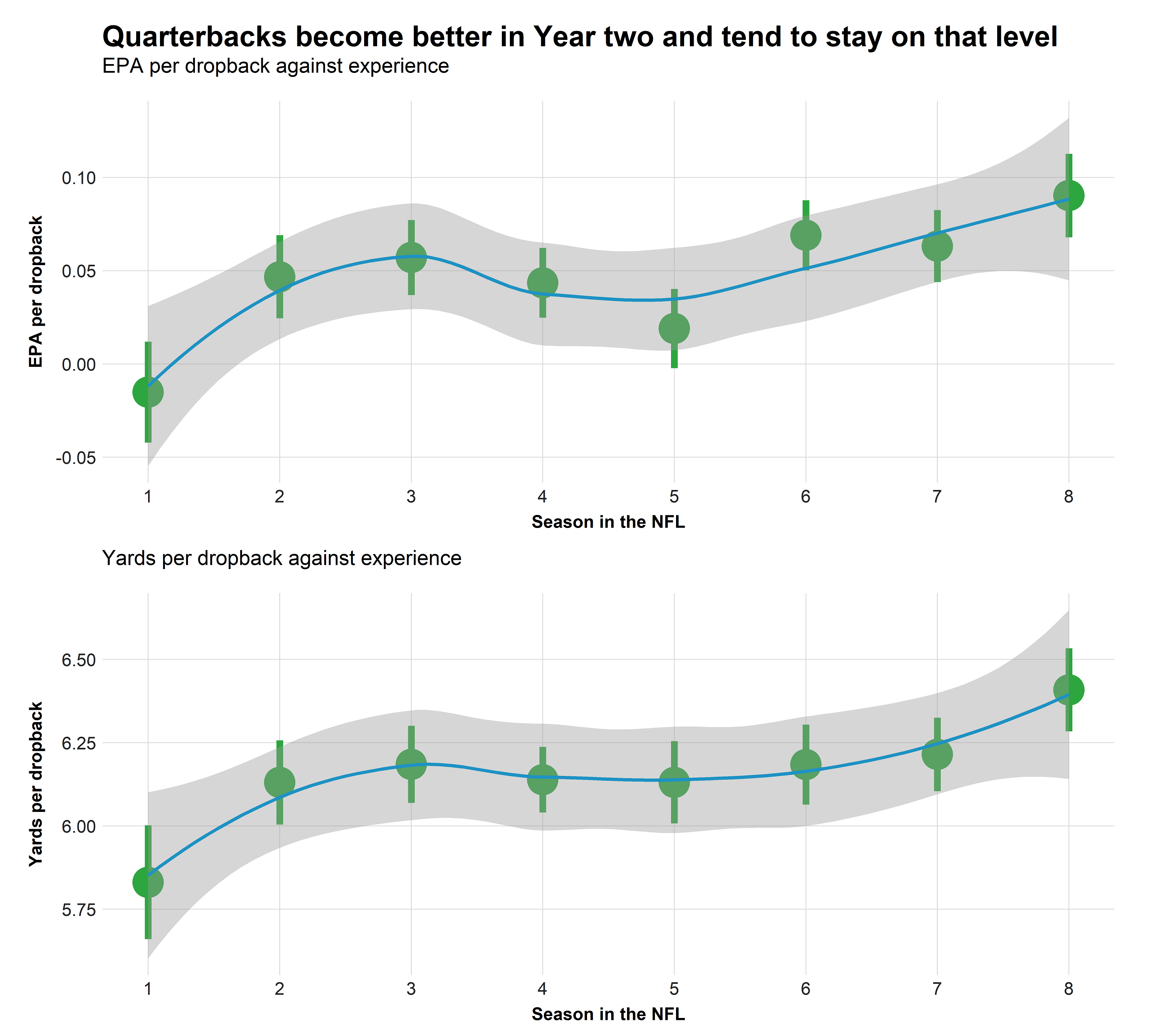

The chart above measured the performance by PFF passing grade, but using other measures of overall QB play shows a similar pattern:

This doesn’t mean that all quarterbacks stop developing after Year 2, it's just that the typical passer tends to develop in Year 2 and stay at that level.

Of course, the quarterbacks who stay in the league for a long time are not typical and usually become even better with more experience, but at the time they are entering their second year, we rarely know who belongs in which group.

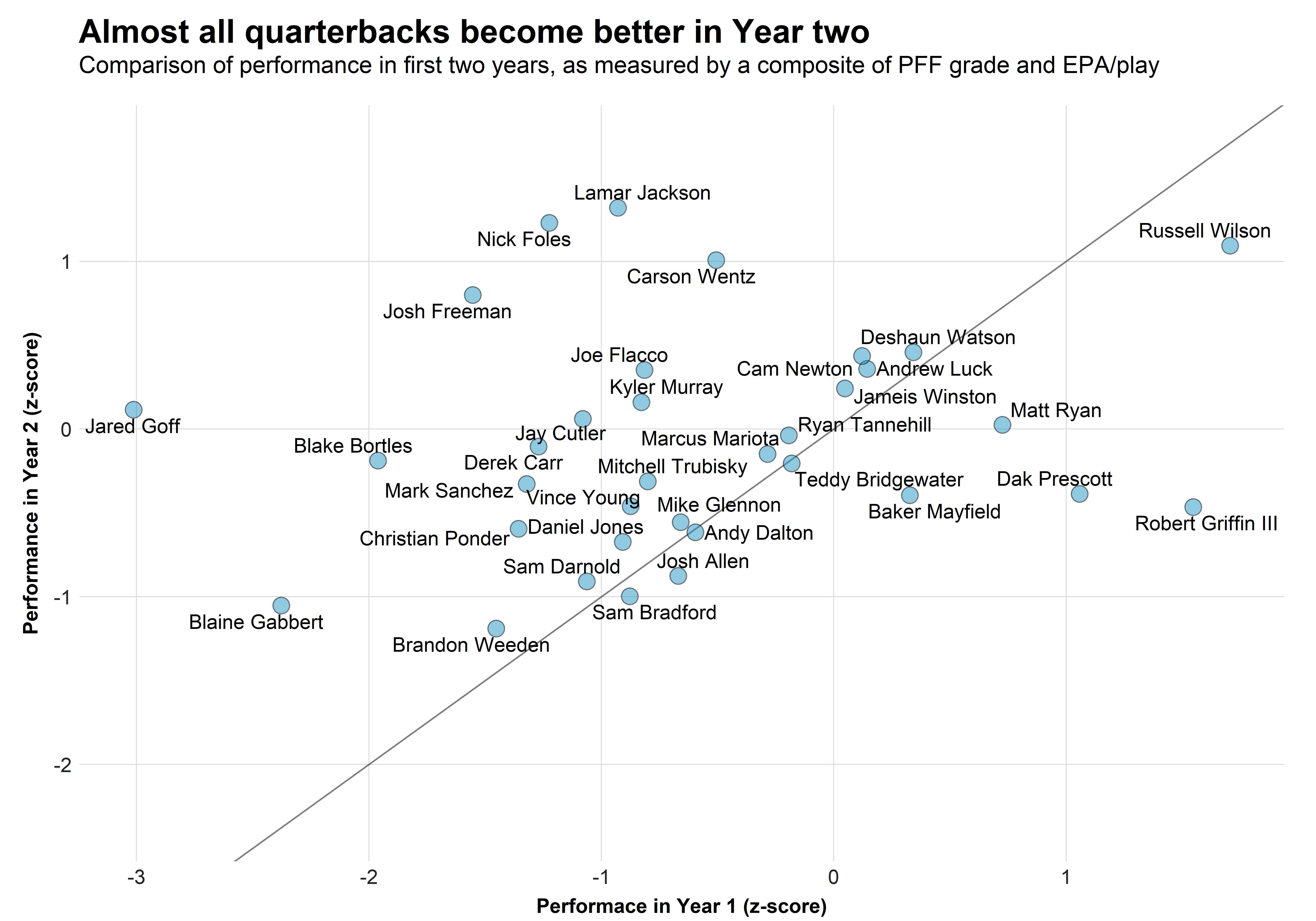

However, the second-year jump seems to happen for almost every quarterback, even those such as Blaine Gabbert, Blake Bortles, Mark Sanchez or Josh Freeman who never break out completely.

It becomes apparent that the only way to not get better in Year 2 is to hit the ground running in Year 1, an effect that can be seen with quarterbacks such as Russell Wilson, Matt Ryan, Dak Prescott and Robert Griffin III.

The only other exception was Josh Allen, which falsely led us to assume he would have a very low chance to break out in Year 3. However, he also had some kind of a second-year jump, it just came late in the season when he generated 0.05 expected points added (EPA) per play in Weeks 11 through 17 in 2019 after generating only -0.05 EPA per play through Week 10.

What drives this kind of improvement? Basically, all direct indicators of quarterback performance improve in the second year, but when we look at schematic indicators, there is one that stands out: being able to make reads over the middle of the field that let you attack beyond the sticks and between the numbers on the same play.

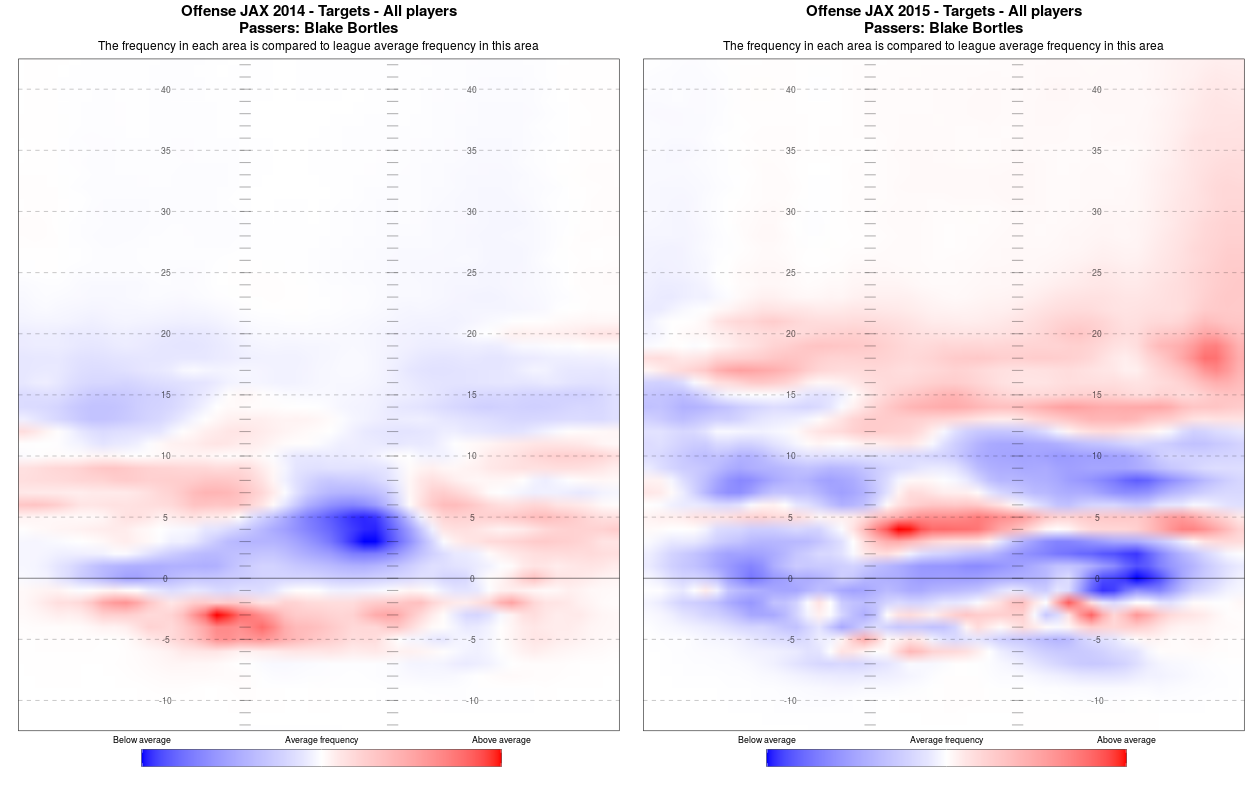

To illustrate that, we look at the passing heatmaps for several quarterbacks who significantly improved in Year 2.

Blake Bortles

The effect is apparent for Bortles, as he attacked the deep middle much more often in Year 2.

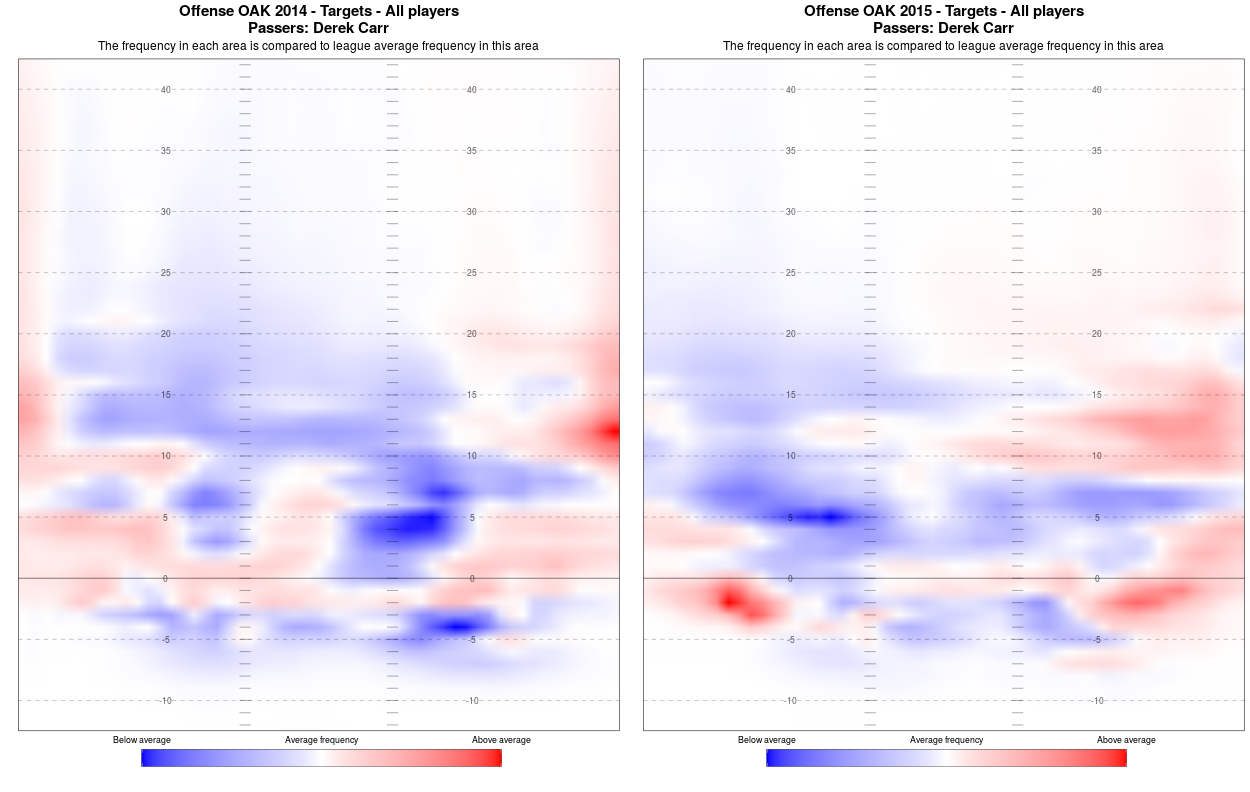

Derek Carr

In his rookie year, Carr mostly attacked deep by throwing down the sidelines, and we see a huge blue spot over the intermediate and deep middle. With more experience, he was able to attack those areas more.

We find similar patterns for other quarterbacks who improved a lot in Year 2:

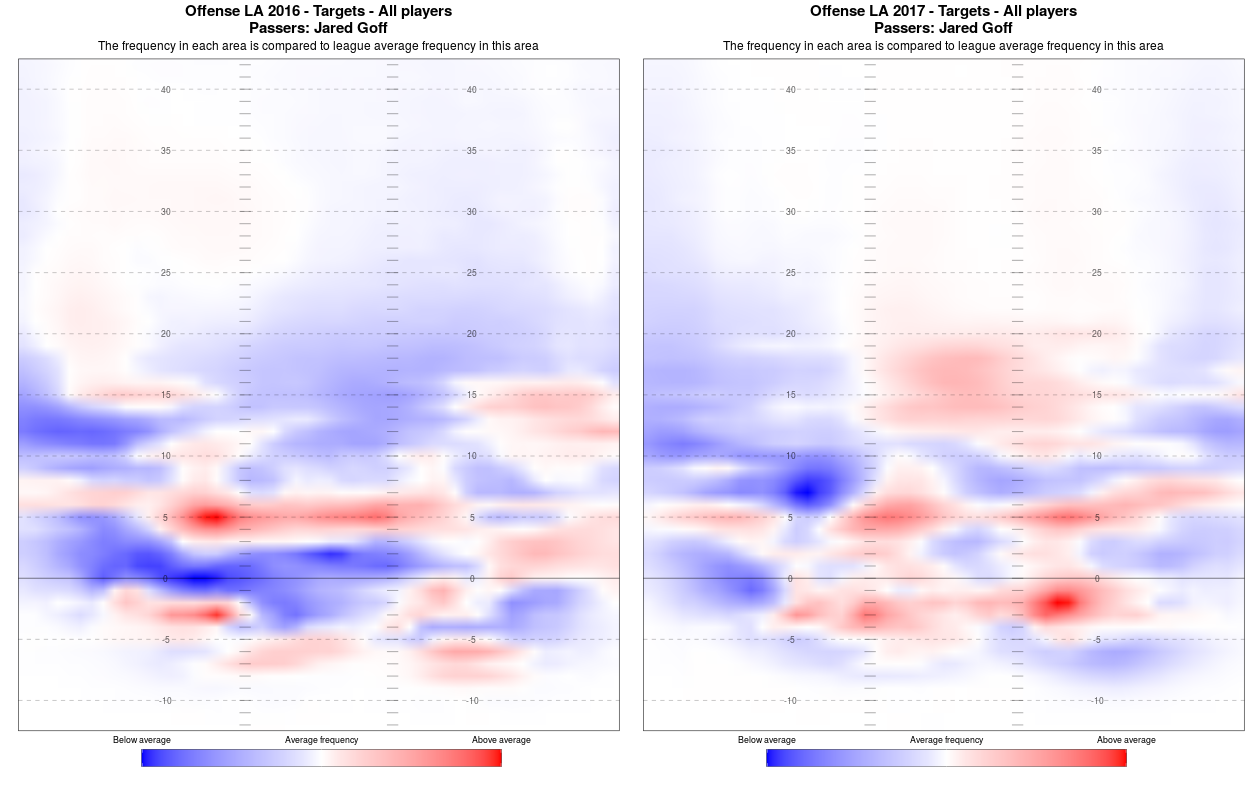

Jared Goff

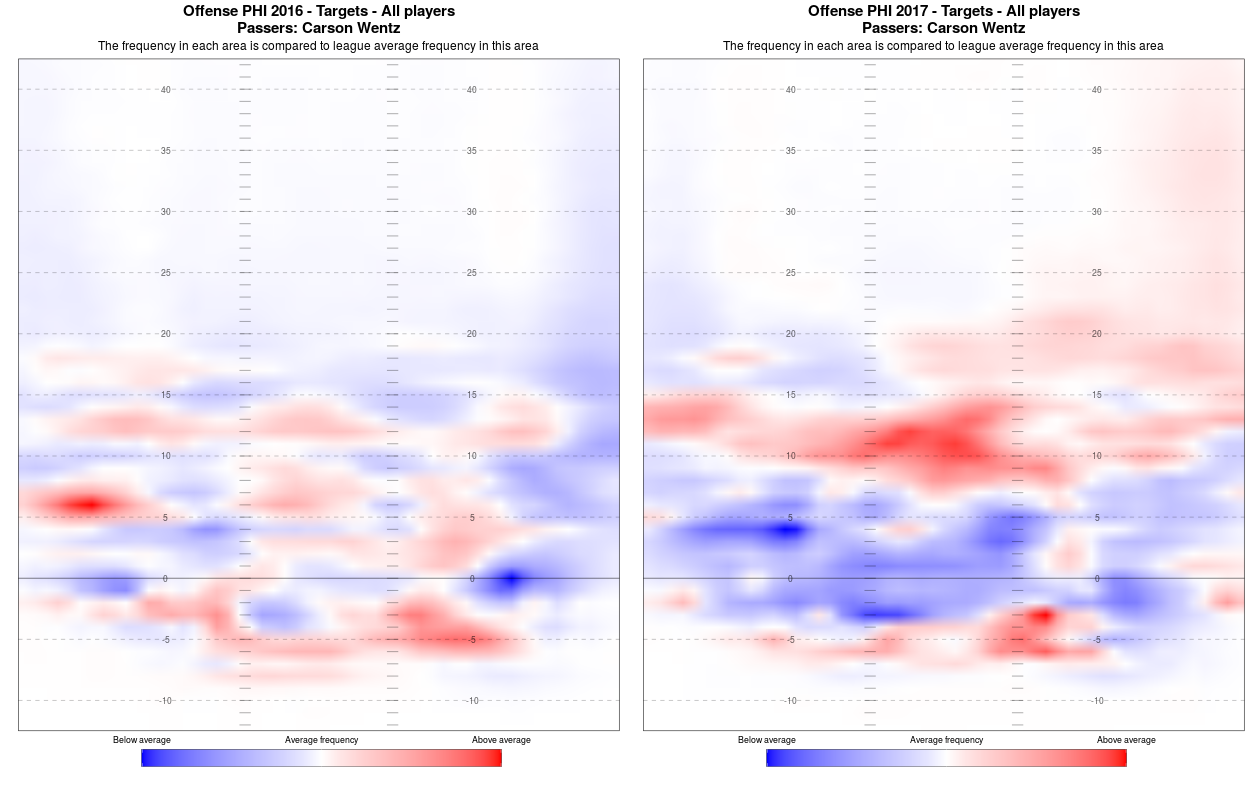

Carson Wentz

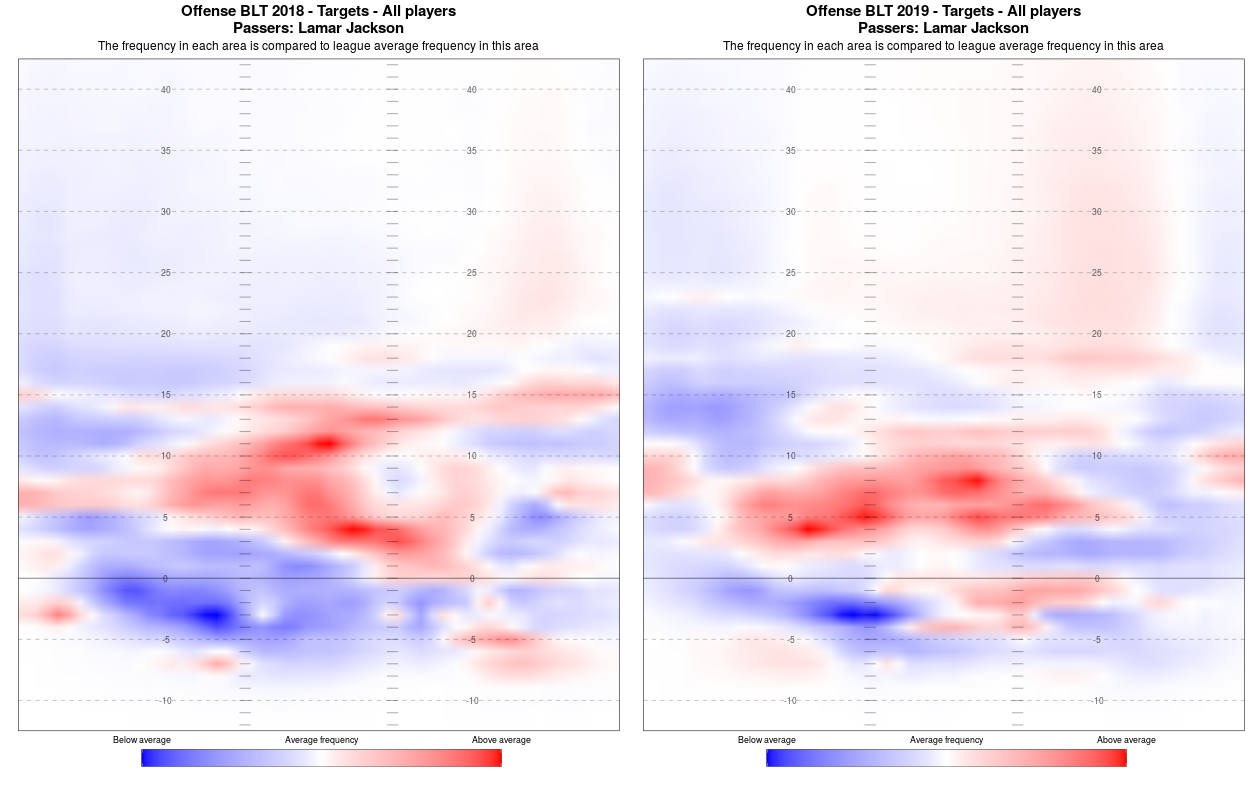

Lamar Jackson

All these maps would suggest that the second-year jump is driven by the ability to attack the middle of the field, and we indeed find a positive correlation between the magnitude of the second-year jump and the increase of the percentage of targets that a quarterback throws toward the intermediate and deep middle. The correlation coefficient is 0.46.

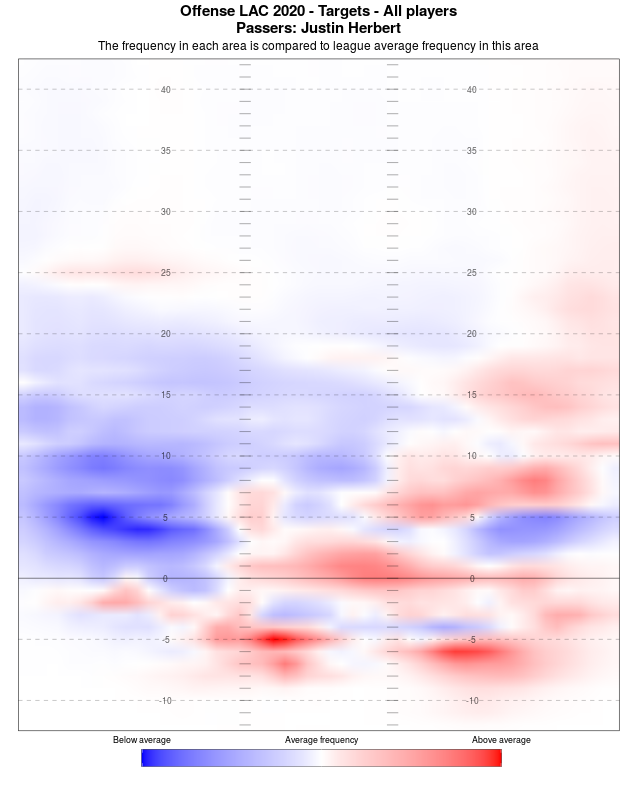

Interestingly, if we look at last year’s rookie of the year, Justin Herbert, he didn’t necessarily attack the deep and intermediate middle of the field very often, so there still seems to be room for improvement for him.

To be more concrete, his rate of targeting the area between the numbers 10 or more yards downfield ranks 39th among 59 rookie seasons with at least 150 dropbacks since 2006.

Can we predict the second-year jump?

While almost every quarterback improves, the level of improvement is not the same for each quarterback. After Lamar Jackson and Carson Wentz played at an MVP level in their second years, many people expected the same from Kyler Murray and lost money betting on him to be MVP. He improved, of course, just not as drastically as others before him.

Is there a way to predict the magnitude of the second-year jump, or is it mostly random? It’s obvious that players who have more room for improvement tend to improve more, so every indicator that represents a positive for quarterback performance has a negative correlation to the magnitude of the second-year jump.

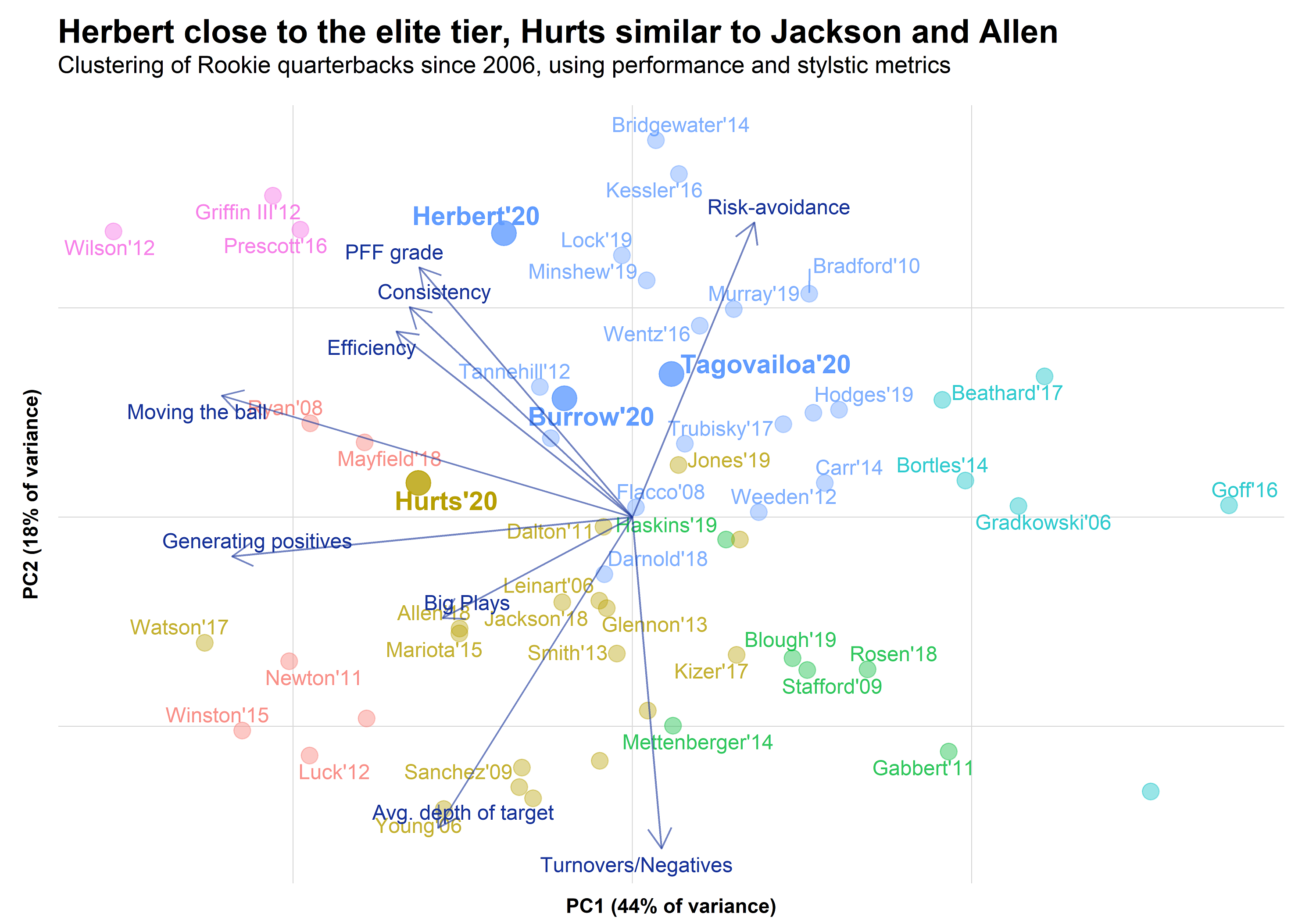

To measure the effect of multiple indicators toward the second-year jump, we will use clustering for the seasons of rookie quarterbacks as introduced earlier this year.

Compared to last time, we will add another feature to the clustering algorithm: the percentage of targets over the intermediate and deep middle. Hence, the result of the clustering is not exactly the same, but it looks pretty similar.

To predict the magnitude of the second-year jump independent of the results in Year 1, we regress the second-year jump of each of those quarterbacks (minus the 2020 draft class) against all 17 principal components and remove all components which are either mostly describing results (the first two components) or are not statistically significant.

What remains is a linear model with an R-squared value of 0.14. That’s not particularly high, but this is a pretty solid figure when it comes to predicting performance in the NFL.

Using this model to predict the second-year jump for the 2020 draft class, we get the following results (with the jumps measured in standard deviations):

| QB | Jump in EPA | Jump in grade | Composite jump |

| Jalen Hurts | 0.58 | 0.83 | 0.70 |

| Justin Herbert | 0.55 | 0.79 | 0.63 |

| Joe Burrow | 0.41 | 0.33 | 0.37 |

| Tua Tagovailoa | 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.31 |

We should note that these figures are the expected improvements independent of the actual results in Year 1, hence it will be difficult for Herbert to actually achieve such a huge jump due to natural regression to the mean (which we especially expect for his performance under pressure).

The numbers are more realistic to achieve for the other three quarterbacks whose rookie seasons were closer to the average rookie season. Nevertheless, it suggests that Herbert’s skill set has probably not peaked yet despite a strong rookie season, which is very good news for the Los Angeles Chargers and their fans.

Naturally, the actual observed second-year jump also depends on the supporting cast. But in that regard, none of the four sophomore quarterbacks has a reason to complain: The Eagles added Devonta Smith and will hopefully have a healthy offensive line. The Bengals added Riley Reiff in pass protection and Ja’marr Chase to the receiving corps. The Dolphins added Tua’s college target, Jaylen Waddle. The Chargers vastly improved Herbert’s pass protection.

As far as this is concerned, all four of last year’s rookies are ready to showcase their skills come September.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.