Father Time is undefeated, and he often runs up the score against NFL players late in their careers. Since turning 35 in 2017, Ben Roethlisberger — excluding his injury-riddled 2019 campaign — has topped a 75.0 season-long passing grade only twice, in 2017 and barely in 2018. In the prior 11 seasons PFF has charted, he had failed to do so just twice: 2006 and barely in 2008.

But Father Time is playing a different game against Tom Brady. Since turning 25 in 2012, Brady has recorded a sub-80.0 season-long passing grade only once, with a still-solid 76.0 mark in 2019.

Click here for more PFF tools:

Rankings & Projections | WR/CB Matchup Chart | NFL & NCAA Betting Dashboards | NFL Player Props tool | NFL & NCAA Power Rankings

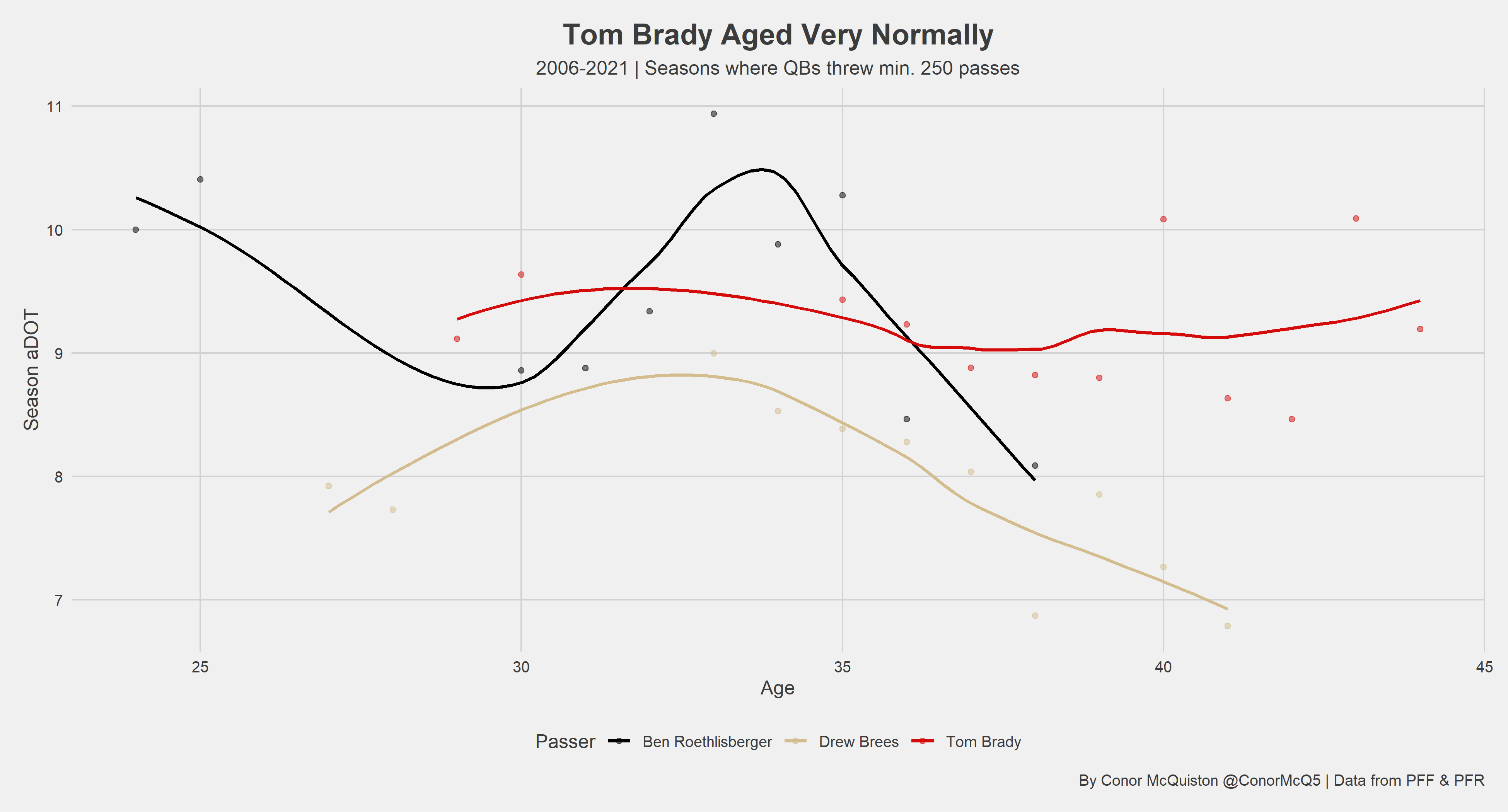

The main driver behind Roethlisberger’s downfall has undeniably been his declining arm strength, leading to an increase in extremely quick checkdowns. This once again is in stark contrast to octogenarian Brady, who is tied for the 10th-highest average depth of target (aDOT) in the league this season. This difference becomes most obvious when comparing the pair’s aDOTs over time. And as a reference point, we’ll also throw in Drew Brees:

The most important part of this is that Roethlisberger fell off a cliff particularly fast. However, this begs an interesting question: Is Roethlisberger aging in a typical manner whilst Brady is simply an anomaly? We will attempt to answer that using aDOT as our measuring stick for how much a quarterback is aging. The thought process behind this is that as a quarterback ages, the primary issue is purely physical. We’ll assume that older signal-callers can still mentally keep up, just that they are physically unable to put as much velocity on the ball compared to when they were younger. This should result in lower aDOTs, as they can’t push the ball downfield or into intermediate tight windows as often. This isn’t a perfect tool, but we’ll address that later.

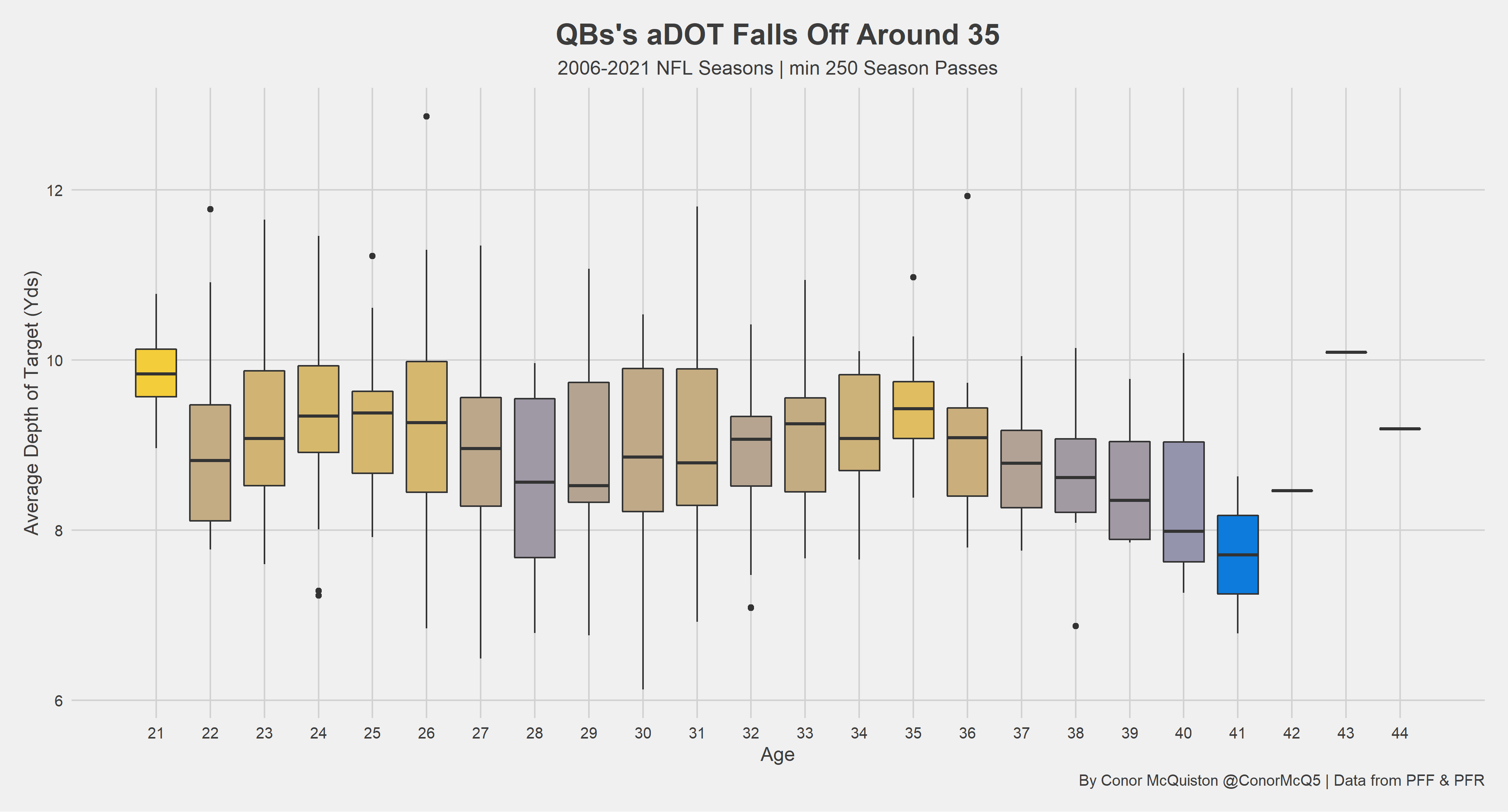

Looking at raw aDOT, we see that it begins to fall off around a quarterback's age-35 season. So, from here, we can comfortably say that quarterbacks begin to lose some arm strength around age 35. But the glaring issue here is that aDOT is not solely controlled by the quarterback — it is inextricably linked to the play calls. A signal-caller can’t throw 50 yards downfield if there aren't receivers 50 yards downfield.

Therefore, it is wholly possible that the depressed aDOTs of our elder quarterbacks are mostly the result of their play callers being overly conscious and calling shorter passes despite it being unwarranted. There is also a survivorship bias where only successful quarterbacks make it to their 12th season and beyond, but since this is the exact sample we’re interested in, this is fine. The larger, or smaller to be technical, concern is that with the advanced ages, the sample size decreases rapidly. In particular, once we reach an age-33 season, the sample size is never larger than 13 and is typically around 10. This means we are unable to make any definitive statements but can hopefully recover some directional information.

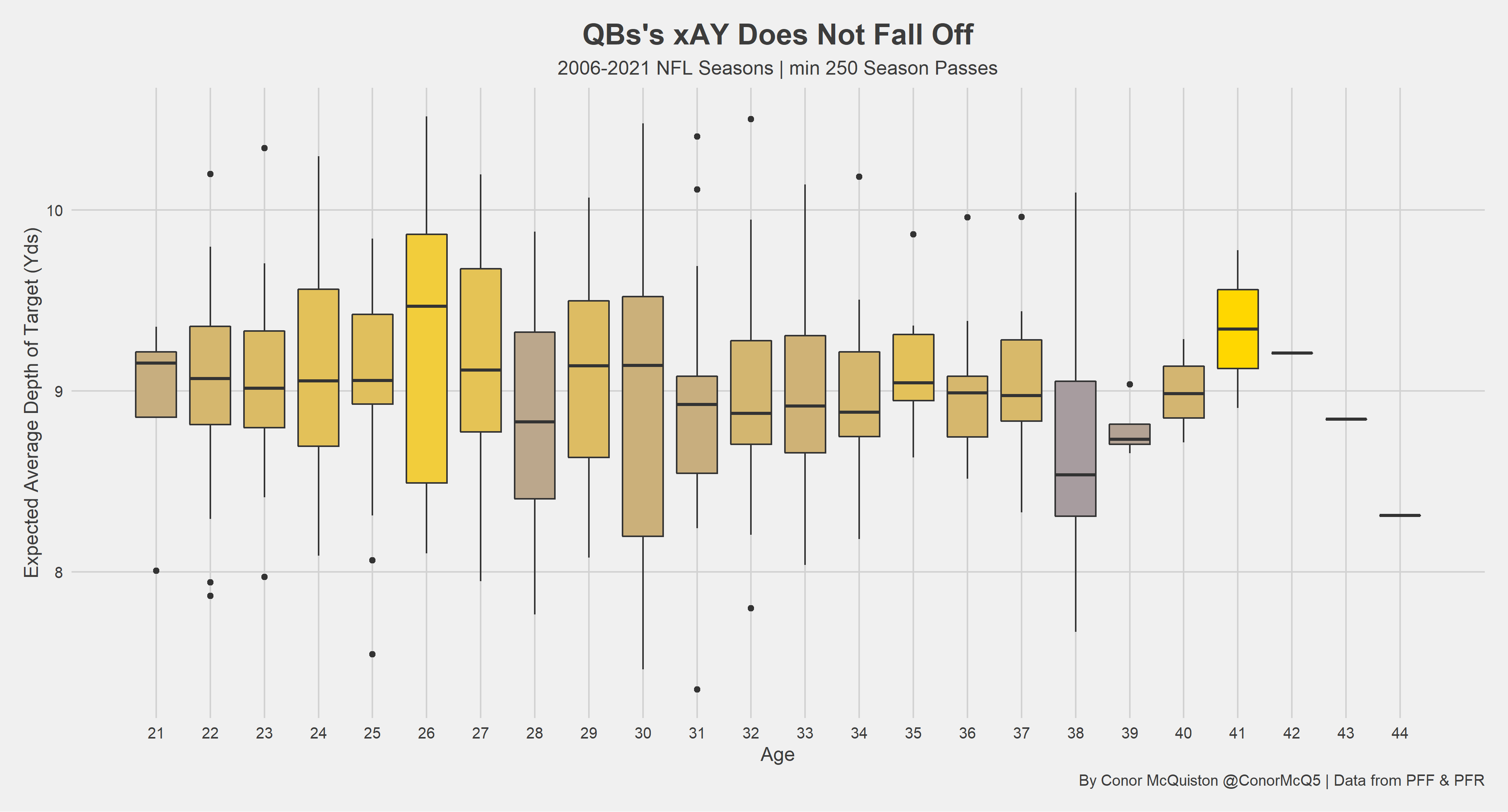

So, the main task at hand is to control for a quarterback’s play calls to see if the depressed aDOTs of older players are the result of more conservative play calling. If they are, we would expect to see expected air yards (xAY) decrease with age, particularly around a quarterback's age-35 season. To generate this xAY, we fit an Extreme Gradient Boost (XGBoost) model to predict a given pass’ air yards based on the current game state, the type of drop back, if the offense was in shotgun and if a play-action pass or screen was called.

xAY appears to not drop off until later in a quarterback’s career, if at all. For just about every particular age, the overall average xAY (9) is contained between the distribution's 25th and 75th percentile. This, along with consideration of the sample sizes of the older distributions, tells us we cannot make a strong claim about how xAY changes with age. Directionally, however, it appears that we cannot say there is a clear age at which coaches begin changing their play calling to account for their quarterback’s decreasing physical abilities. This makes sense, as the effects of aging are far from uniform, and even if a coach is able to ascertain exactly when a passer is about to fall off, that veteran player may still protest to prevent the change from happening.

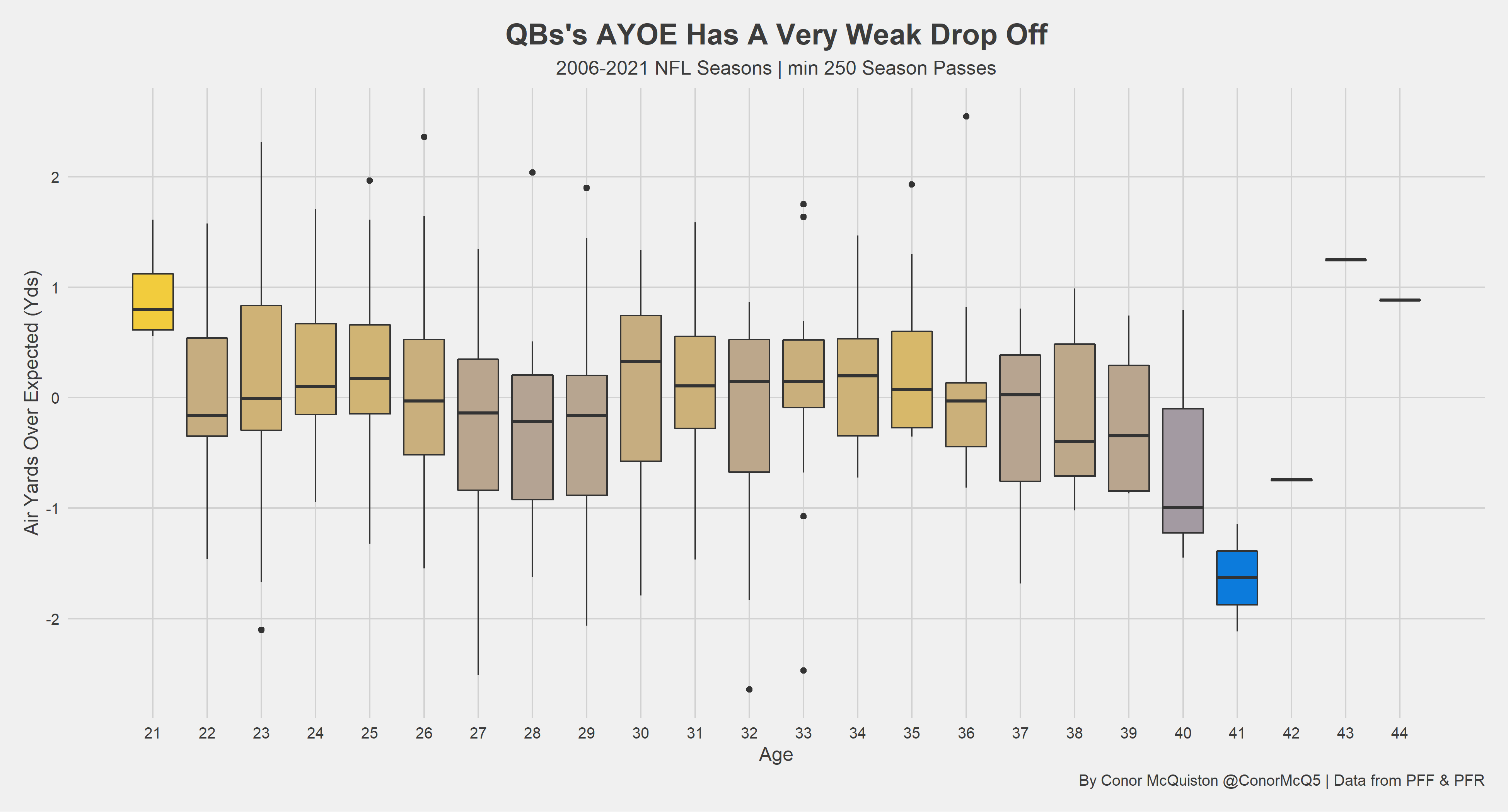

Now that we have a measure for how far signal-callers are expected to push the ball down the field, we are able to get estimates for how far they push it down the field relative to that expectation. Using this, air yards over expected (AYOE), as a measure for arm talent is still problematic, as it is in part capturing quarterback style. Some passers just prefer to push the ball as far downfield as they can. How far they are able to throw downfield, even if they do prefer it, however, is still limited by the play call and what their body allows them to do. Controlling for the play call, as we have done, allows us to better isolate and get an insight into what their body is capable of, thus giving us information about how the quarterback has aged.

Once again, we get very little signal as to a uniform drop-off age. There is a visible dropoff beginning in the late 30s (age 37, by my eye), but these sample sizes are too small to make definitive claims. Thus, we are left with the directional claim that there does not appear to be a uniform age at which quarterbacks start to physically fall off as measured by AYOE.

This is intuitive. The people we are concerned with are some of the best athletes in the world and are masters at their specific craft, spending millions of dollars and hundreds of hours on their health each with unique biologies. Add this to the fact that each quarterback has different workloads in their practice weeks and different injury histories, and it is very unsurprising that we can't reach a uniform age of falling off for every quarterback.

Related Content: NFL Week 7 Quarterback Rankings via Kevin Cole

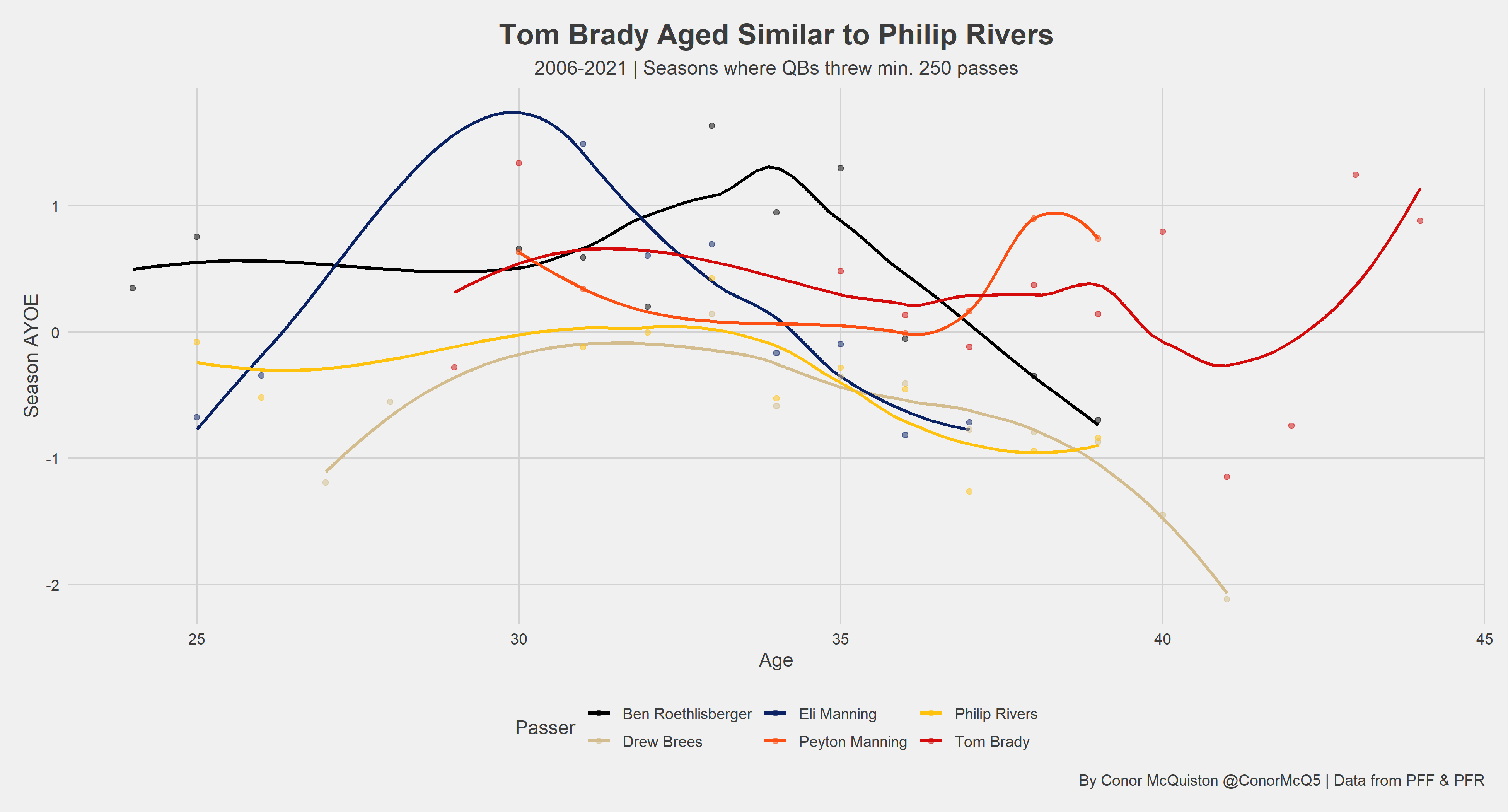

This is all fine and dandy, every signal-caller is a special snowflake, but what does this tell us about Brady? Our only real option is to compare him to similar players using the best metric we have: AYOE. This is a qualitative measure, so we cannot say anything definitive about his aging by this comparison, but we can say if he stands out. The direct comparisons I will be using are Peyton Manning, Eli Manning, Drew Brees, Ben Roethlisberger and Philip Rivers since all of their peaks were around the same time and environment as Brady (late 2000s, mid-to-late 2010s):

For most of his compatriots, there is a point where their AYOE begins to decline. This can be very steep at times — Eli Manning, Roethlisberger and late Brees stand out as examples. Or it can be relatively gentle — Rivers and Peyton Manning stand out in this regard. We also see several flaws in this approach, where white-hot stubbornness and surely not physical ability propelled 2015 Peyton Manning to an AYOE of nearly 1.

Brady’s long-term success in this regard is contextualized to be not nearly as absurd as it seems, even if the end is inflated somewhat by the Tampa Bay Buccaneers’ scheme. Brady appears to follow a similar trajectory of Rivers and Peyton Manning’s aging, just transposed by several years. His trajectory is actually shockingly similar to another “aging” quarterback.

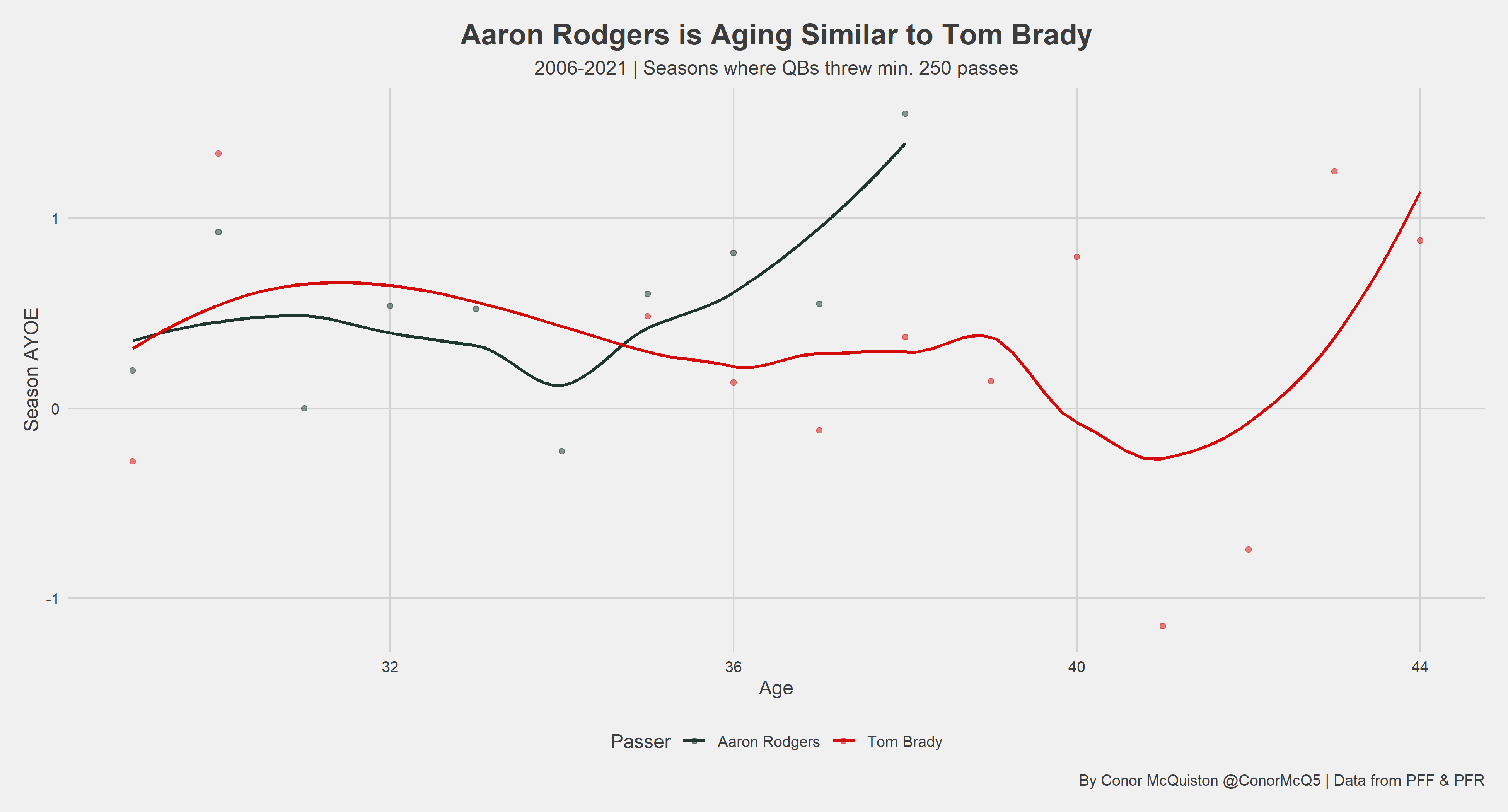

Aaron Rodgers is following an almost identical aging trajectory as Brady, which is to say there is not one. Granted, it is extremely likely that Rodgers’ current AYOE will fall back to Earth as the season goes on, but even so, he appears to be equally ageless.

So, where does this leave us with Tom Brady?

The dedication and discipline required to keep his body in this shape well into his 40s is incredible and deserves applause. But the general trajectory that he’s aged on is not wholly unique, and it appears we have another quarterback currently on the same path in Rodgers.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.