Quarterback pressures have been charted and systematically investigated — notably so by my colleague Eric Eager — for a while now. And over that time, the analytics community has come to accept the fact that turning pressures into sacks is not a repeatable skill.

As a result of this research, the landscape of NFL analysis even outside the analytics community has shifted from focusing on sack totals to focusing on pressure totals. This makes perfect sense. Pressure totals yield a high sample size, and the reasons why the process of turning a pressure into a sack is “noisy” sound reasonable: Once beating his blocker, the pass-rusher is dependent on his secondary winning the matchup with the receivers. And as of today, it is well known that a quarterback — along with the help of the offensive scheme — controls his own sack rate.

[Editor’s Note: PFF’s Player Grades, WAR metric, etc. are powered by AWS machine learning capabilities.]

By looking at pressures instead of sacks, it was more than obvious that Lorenzo Alexander’s 2016 season — a season in which he led the league in sacks for a long time — was a fluke, as he suddenly turned 26% of his pressures into sacks.

From 2017-19, Alexander actually posted a higher pressure rate (15.4% compared to 13.1% in 2016), but he never came close to his 2016 sack rate (2.2% compared to 3.4% in 2016). This was because he reverted to turning only 14.6% of his pressures into sacks, a rate that was, coincidentally, precisely the league average from 2017-19.

In other words, Alexander didn’t suddenly turn into a “sack artist.” He was just a bit lucky during one season.

Revisiting priors

A few weeks ago, our friend Josh Hermsmeyer published an insightful article on FiveThirtyEight.com in which he analyzed how pressures and sacks affect offenses when it comes to drive outcomes.

As I was reading this article, an immediate thought came to my mind: What if pressures are turned into sacks more often on third (and fourth) down? This is an intuitive question since quarterbacks are more likely to hold on to the ball and make something happen on third down. After all, a throwaway or scramble out of bounds for 2 yards on third-and-7 is not really an option that helps your team.

This means that, while sacks are more valuable than pressures, measuring drive outcomes make the difference look a bit larger than it is, as sacks happen disproportionately often on third down and they end the drive basically 100% of the time when they do occur in these situations. If a quarterback were to behave just as he would on first down, he would maybe throw the ball away under pressure, and instead of a sack, we would measure a mere pressure that ended the drive.

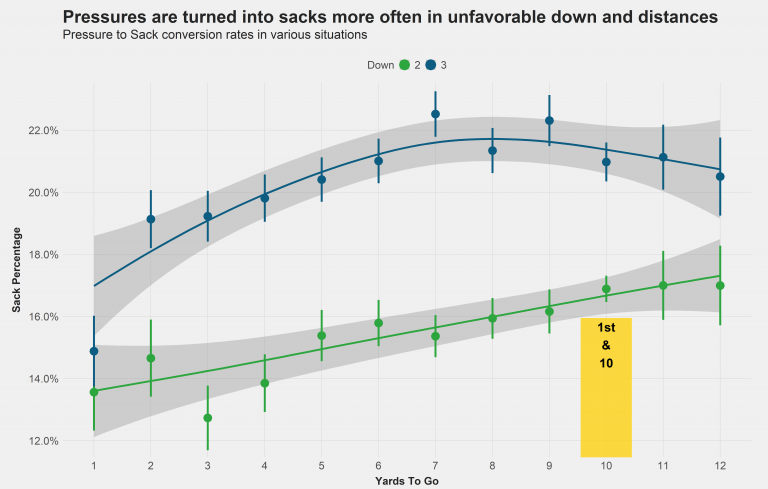

Independent of this, I collaborated with PFF senior analyst Sam Monson to produce an article about how pressure affects the opposing offense, additionally incorporating the source of the pressure. I used this opportunity to investigate how different downs and distances affect the rate at which pressures are turned into sacks, and I found that the situation does significantly alter the rate, as pressures are turned into sacks more often on third down and also with more yards to go (most likely because the opposing plays need longer to develop).

It certainly takes skill to register a pressure (or a pass-rush win) on second-and-2, but it’s unlikely to actually turn into a valuable sack since the opposing quarterback likely has a promising short passing option at his disposal, which should be enough to pick up the first down.

It’s interesting that the effect of the number of yards to go is seemingly reversed on third-and-very long, probably because there this a threshold at which the offense has “already given up” and is willing to play for field position, i.e., the quarterback is more willing to throw the ball away, check it down or employ a quick passing concept that is called from the sideline.

After having established that not all pressures are the same when it comes to creating sacks, it’s a natural question to revisit our prior conclusion — that turning pressure into sacks isn’t a repeatable skill.

After adjusting for situational factors, can the adjusted rate at which a pass-rusher turns pressures into sacks help us forecast sacks better than before? From an intuitive standpoint, both options seem possible:

- One could argue that a pass-rusher attempts to win his matchup on every single play, but he can’t really influence exactly when he wins, so the situations in which he generates pressure are unstable from year to year. This might have caused the noise we found in the sack data.

- On the other hand, it could be the other way around, especially for role players who rush the passer only in specific situations. If we haven’t found signal in sack data before adjusting for the situation, we would expect that turning pressure into sacks would be even noisier after adjusting for the situation.

Exclusive content for premium subscribers

WANT TO KEEP READING?

Dominate Fantasy Football & Betting with AI-Powered Data & Tools Trusted By All 32 Teams

Already have a subscription? Log in

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.