I was recently listening to an excellent podcast episode of The Athletic Football Show with PFF's own Diante Lee as a guest. Near the end of the show, there was a discussion on shifts in defensive philosophy — specifically, how teams are forcing offenses to more aggressively throw the ball down the field on third downs and using coverages to limit bigger plays on early downs.

The discussion interested me since it’s fairly well-known that average depth of target (aDOT) has been generally declining in the NFL over the past several years. PFF's data runs from 2006 to 2020, and aDOT overall has fallen from around 9.5 yards to 8.7 yards over that span. My preexisting assumption was that the general trend of falling aDOT would be applicable to all offensive situations, as teams have substituted short passes for runs on all downs while massively increasing their usage of screen passes and shorter pick plays.

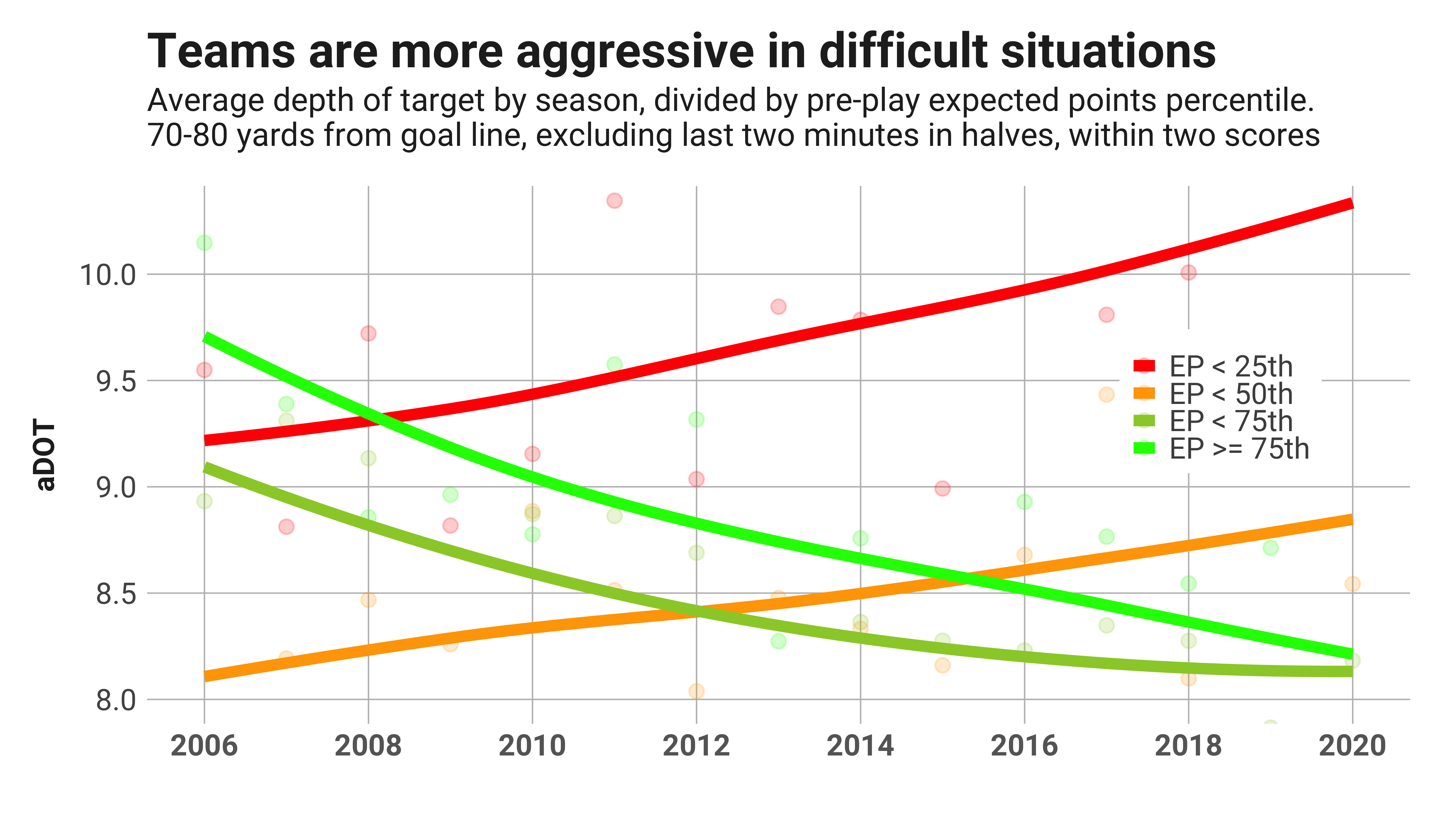

What I found in my analysis is that the overall trend of a slight, steady decline in aDOT masked dramatic shifts in how aggressive offenses have been throwing the ball in different situations. Dividing dropback data by expected points (i.e., how many points the offense is expected to score on a given drive based on down, distance and field position) showed that teams are now more sensitive to potential losses in different passing situations and are now aligning their willingness to take risks with expected outcomes.

The NFL appears to be getting smarter in how offenses approach different circumstances. While the influence of different defensive schemes is part of the reason for offenses’ situation shifts, the data shows long-term trends that hint at a greater influence and first-mover advantage by the team with the ball, as well as a steady maximization of passing value in all circumstances.

Shifts in passing aggression

Simpson’s Paradox is defined as “a statistical phenomenon where an association between two variables in a population emerges, disappears or reverses when the population is divided into subpopulations.” This phenomenon applies to NFL offenses’ willingness to throw downfield once we break the population of passes into the offenses’ expected points before each play.

The chart above has divided all plays in the dataset into quartiles by expected points. To limit the influence of field position, I restricted the data to plays that were between the offenses’ own 20- and 30-yard lines. I also excluded end-of-half situations and blowouts (i.e., more than two-score leads) to limit the influence of outlier situations.

Exclusive content for premium subscribers

WANT TO KEEP READING?

Dominate Fantasy Football & Betting with AI-Powered Data & Tools Trusted By All 32 Teams

Already have a subscription? Log in

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.