At a surface-level viewing experience, very little in a basketball game would inspire comparison to football. But being wired to consume all competition through the lens of the sport I know best and see most, I can’t help but notice some of the similarities on the defensive side of the ball.

I love that high level defensive basketball resembles man-match coverages in football. https://t.co/pXj4VvojYf

— Diante Lee (@PFF_DLee) September 19, 2020

What I’ve found most compelling is the constant debate about personnel usage. It sounds familiar to what we hear every NFL offseason, as data is reviewed and compared to recent history to discover trends and talking points therein. In hoops, the big buzzword is playing “small ball,” using a conventional perimeter player in place of the traditional big man.

When small ball is clicking defensively, it's about switching and swarming, taking air space away from the offense and forcing the ball away from the best scorers. When it’s not, offenses punish these lineups at the rim and on the backboard. This is the tug of war of aggressively creating mismatches versus playing what’s best, given the situation.

At the core of understanding, any sport is an issue of matchups. If I got paid every time I heard the phrase, “nickel is the new base” in football, I’d have a hard time carrying all the coins. There’s power in the phrase because it’s supported by the numbers (over 58% of all snaps from 2018 to 2020), but it collapses under its own weight.

It’s not much at all about what’s new on defense, and while “nickel is the new base” flows better phonetically than “11 personnel is the new 21 personnel,” the truth is that any evolution on defense is reflective of the changes made by the offense.

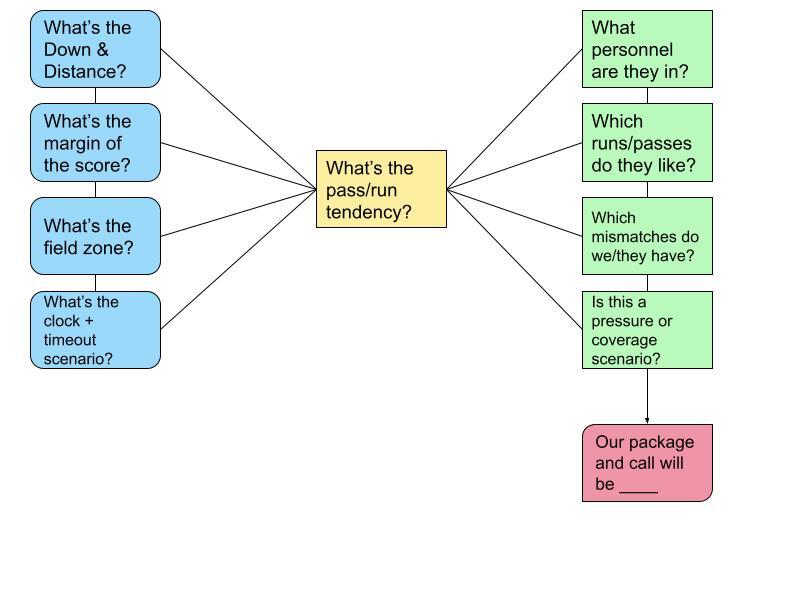

Conventionally, a defense isn’t constructed independently of an offense. Strategically, defensive football can be visualized as a flowchart with an exponential amount of factors and subfactors that influence personnel and play calling.

These factors, as much as it stings to admit, are rarely — if ever — within a defensive coordinator's control. Defense is about matching up against the tendencies, tactics and team makeup of the offense, given the game situation.

But, like playing small ball, there come times in a game, and throughout a season, where it’s appropriate to lean harder into creating certain matchups or playing a tendency or getting the best 11 guys on the field for that moment in time.

Defensively, the football equivalent is playing with dime personnel — six defensive backs. Teams traditionally use this personnel on obvious passing downs, with 43% usage on third-and-long (7-10) over the past three years. In the same span, in spite of returns of -.032 expected points added (EPA) per play, dime defensive structures are still treated as specialty packages, being used only at an average of 9% on first and second downs.

This lends to the idea that coaches fundamentally believe that defense is about matching bodies. With that in mind, I wanted to examine whether teams were being punished in situations where they decided to play unconventional personnel groupings — be them bigger or smaller — against an offense.

The run/pass tendency in each personnel grouping is an important context, as well, when considering whether it’s rational to defend the play instead of the personnel. If there’s a clear tell in tendency or performance, there may be an opportunity for success on the margins by playing tendency via personnel.

Personnel Matchup Data: 2018-2020 NFL Averages

| Offensive Personnel vs. Conventional Defensive Personnel | Run/Pass Tendency by Personnel Grouping | % Split of Def. Snaps in Conventional vs. Unconventional Personnel | EPA/Play Difference in Conventional vs. Unconventional Defensive Personnel |

| 21 Personnel (Base) | 52/48% | 60/40% | -.069/.072 |

| 12 Personnel (Base) | 48/52% | 60/40% | .029/.037 |

| 11 Personnel (Nickel) | 29/71% | 76/24% | .021/-.038 |

| 10 Personnel (Nickel) | 20/80% | 60/40% | -.133/-.148 |

The past three years of data pours water on the seeds planted in my mind from watching the NBA — it wouldn’t kill teams to consider playing the tendency via personnel over matching bodies. In fact, short of 21 personnel, unconventional matchups perform well compared to more typical packages, if not outperforming the conventional defensive matchup outright.

When there are three receivers on the field, which accounts for around 60% of the snaps since 2018, it is a passing situation. If playing dime can perform at or above the level of their conventional counterparts, it would serve a defense to mix up their looks in an era of offensive versatility and mismatch hunting.

To project whether playing more dime against 11 personnel is sustainable, we would need to control for special situations by honing in on first and second downs. This eliminates things like running back draws and screens or deep heaves looking for completions or pass interference on third-and-long. If defenses are being heavily punished with the run while playing dime on first and second downs, for example, it would make sense to simply play nickel and adjust within the package to defend the heavy pass tendency.

Looking first at the pass, dime outperforms nickel in yards per attempt, explosive play rate, passer rating and pressure percentage.

Take that for pass rush versus coverage.

First + Second Downs Defensive Performance vs. 11 Personnel (NFL Average 2018-2020)

| Personnel & Data | Nickel Personnel | Dime Personnel |

| Passer Rating | 93.13 | 81.06 |

| Pass Yards Per Attempt | 7.21 | 6.72 |

| Explosive Pass Rate | 14% | 13% |

| QB Pressure Rate | 28% | 34% |

| Passing EPA/Play | .076 | -.072 |

| Rush Yards Per Attempt | 4.64 | 5.51 |

| Explosive Run Rate | 12% | 17% |

| Rush Yards Before Contact | 1.69 | 2.4 |

| Rushing EPA Per Play | -.026 | .004 |

Using designed runs only, nickel defense clearly is better suited to defend the run, giving up fewer explosive plays and fewer yards per attempt while getting to the ball carrier closer to the line of scrimmage than the average dime defense.

The difference in run defense is more than made up for by shrinking the field in the passing game when considering the heavy passing tendency. This sparked my curiosity as to whether teams were playing a different kind of coverage on early downs in dime than in nickel. And yet, in almost 10,000 passing snaps against dime over the past three years, the defense used Cover 1 and Cover 3 more than half of the time — about the same rate as in nickel. This suggests that maximizing coverage players does not inherently break a team's run defense and that playing those schemes requires the same kind of coverage-first mentality as running Cover 4 and Cover 2.

Total Defensive Performance for Top Five Teams in Early-Down Dime Usage, 2020

| Team & Rank | GB | NE | CAR | KC | NO |

| Passer Rating | 11th | 7th | 25th | 8th | 4th |

| Pass YPA | 13th | 24th | 9th | 12th | 6th |

| Pressure Rate | 27th | 20th | 22nd | 14th | 2nd |

| Explosive Pass Rate | 10th | 26th | 11th | 18th | 8th |

| Rush YPA | 18th | 20th | 28th | 24th | 2nd |

| Explosive Run Rate | 8th | 14th | 16th | 5th | 1st |

| Total Success Rate | 20th | 25th | 22nd | 15th | 4th |

| Total EPA/Play | 13th | 24th | 21st | 19th | 6th |

While the data confirmed some of my priors, I fell short of planting a flag saying that dime is the new nickel is the new base. However, it certainly deserves better than the 13% share of defensive snaps it’s had against 11 personnel on early downs since 2018. Last season, three of the top five teams in early-down dime usage ranked in the top half in passer rating and yards per attempt allowed, despite the New Orleans Saints being the only one that generated pressure at an elite level.

Each of the five teams ranked in the top half of the NFL in explosive run rate allowed, showing that fitting the run with more coverage players is possible. There is also plenty to show that playing dime early isn’t a cure-all, as the Carolina Panthers and New England Patriots found the dearth of talent and depth in key spots too much to paper over.

The future of NFL defense is coming from multiple angles, whether it’s playing more Cover 4, running new versions of old-school fronts — such as the bear — or borrowing from college and showing three deep safeties. All roads are leading to the same endpoint: Stopping the modern offense requires a radical investment in coverage schemes and/or coverage bodies.

As for playing small ball in the NFL: As long as a team has the players, it leads to a better chance of eliminating explosive passes by playing better coverage and further entices an offense to run the ball, which is inherently less explosive. If offenses continue to use 11 personnel to pass as they have, expect a growing trend of dime personnel.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.