The NFL offseason is in full swing, and with the 2021 NFL Draft over and free agency coming to a close, all of the hay is in the barn.

Jamal Adams– and Khalil Mack-like trades aside, every team is what it is at this point, with only marquee injuries having much of an effect on the upcoming season moving forward. As such, it’s high time to start talking about some of the decisions that teams have made and how they’ve set themselves up for the short term and the long term.

One of the notions that we’ve explored in great detail — led by the brilliant Timo Riske — is whether teams can consistently overperform in the realm of drafting players. The conclusions are pretty clear, if somewhat nihilistic. As Riske notes, “there is very little reason to believe that draft success at individual positions is predictive.”

What we perceive as strokes of genius are usually just a few steps on what is a relatively short and random walk, with awesome drafts such as those conducted by the 2015 Vikings and the 2017 Saints giving way to selections of Laquon Treadwell, Mike Hughes, Garrett Bradbury, or trades like the one that landed the New Orleans Saints Marcus Davenport in exchange for draft picks that later became Jaire Alexander.

Given the humongous edge bestowed upon a team that acquires top-end play in the draft during the post-2011 CBA era, the draft is where you go to find value, even if the playing field is basically level on a pick-by-pick basis.

Subscribe to

Free agency is generally a lagging indicator of good or bad variance in the NFL draft, with teams chasing losses in the longshot game of the draft with high-priced assets (naively) viewed as “sure things.”

The New England Patriots, having swung and missed on multiple tight ends in the 2020 draft, splurged on Hunter Henry and Jonnu Smith just a year later. After whiffing on Breeland Speaks and Tanoh Kpassagnon, the Chiefs dealt draft capital for Frank Clark before the 2019 season, handing him a big contract in the process. The Vikings, reeling from Teddy Bridgewater’s knee injury and the limitations of Sam Bradford and Case Keenum, splurged on Kirk Cousins in 2018.

Teams such as Cleveland and Baltimore, probably the two smartest franchises in the game, have done a good job of letting things come to them, knowing that it’s very unlikely to “win” March and then subsequently win once they get to the fall. However, not all franchises have the luxury of being able to wait out bad variance. It’s not exactly the same as “the market can stay irrational longer than I can stay solvent” but rather “noise can remain negative longer than I remain in my job.”

What We’re Doing Today

In this article, I want to talk about the frequencies with which teams get into and out of various basins in the NFL, whether they be basins of elite play (think of the New England Patriots or the recent Kansas City Chiefs), basins of truly awful play (think of stretches by Cleveland Browns or the Jacksonville Jaguars) or basins of simply average or below-average play.

It is my hypothesis that teams and fans overestimate the time a team spends in either extreme, which causes them to make (or support) bets that serve as loss-chasing. In the case of trying to prevent a team from being sustainably awful, it could lead to a smaller chance of eventually being sustainably elite.

To study the evolution of team strength, we use our PFF Elo rating system, the outcome of which, from a point spread value, you can find here.

In summary, each team gets a prior rating each year that is a combination of how the team finished the previous year, their betting odds to win the Super Bowl that year and whether they changed head coaches and/or quarterbacks from one year to the next. There is a special reduction for teams that appear to be “tanking,” although this distinction is not liberally applied.

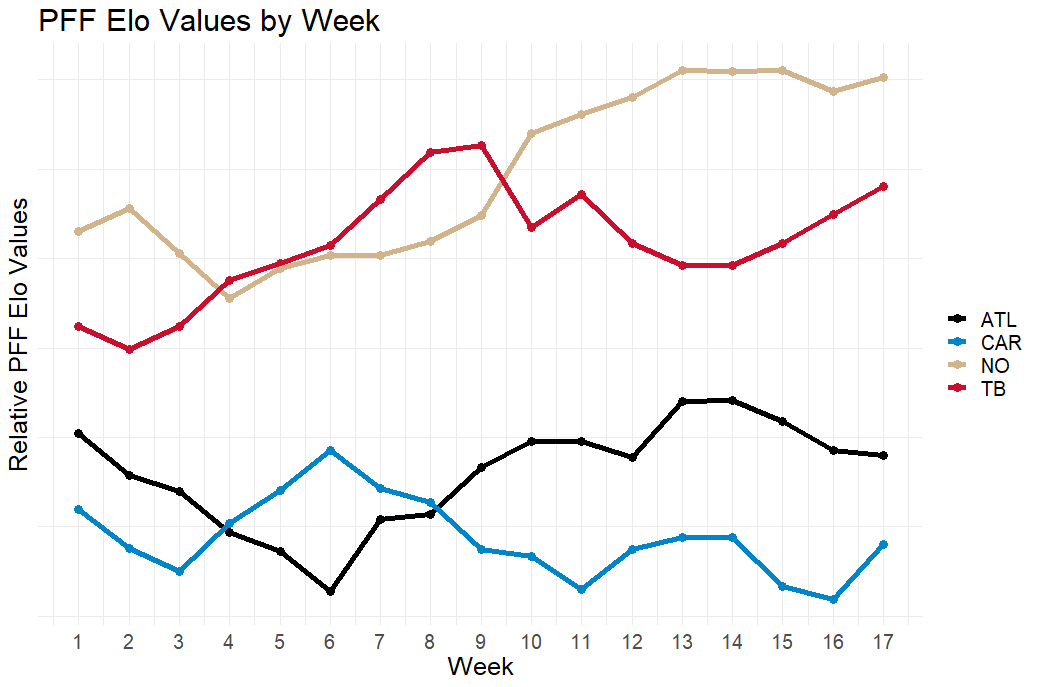

Ratings are updated each week based on how a team grades versus its opponent, relative to expectations. In other words, if the New York Jets play well against the Los Angeles Rams, their rating goes up substantially. If they play well against Detroit, it will go up by far less. An example of the evolution of the PFF Elo ratings for the NFC South during Tampa Bay’s Super Bowl season of 2020 is below:

Using this rating system, we can ask questions such as, what percentage of weeks has Team X spent with an above-average rating? How many times has Team X spent with an “elite” rating? How many times has Team X spent with a “poor” rating?

While we have data from 2006-present in our system, we’re going to use 2011-present to reflect the current dynamic of living under the cheap-rookie-contract CBA.

Weeks Spent Above and Below Average

Here is a table of teams that have spent the most and the least amount of time above or below average (roughly 0 points better than the average team on a neutral field) during the 2011-2020 regular seasons:

| Team | Percentage of Weeks Above Average |

| New England | 97.1% |

| Green Bay | 94.7% |

| Pittsburgh | 90.6% |

| Seattle | 87.1% |

| Baltimore | 78.8% |

| New Orleans | 76.5% |

| Kansas City | 74.7% |

| Philadelphia | 71.2% |

New England’s lone stretch of below-average rating during the PFF era came at the end of the 2020 season when Cam Newton and a declining defense took them to a 7-9 record, their worst since Bill Belichick’s first season of 2000.

| Team | Percentage of Weeks Above Average |

| Cleveland | 10.0% |

| Jacksonville | 10.1% |

| Washington | 16.5% |

| New York Jets | 17.1% |

| Tampa Bay | 18.2% |

| Miami | 20.0% |

| Las Vegas/Oakland | 21.8% |

| Buffalo | 25.3% |

Characteristics of the first group are pretty clear: great quarterback play and elite coaching and organizational functionality. It’s really hard to even touch average, let alone spend time beneath it, with quarterbacks such as Tom Brady, Aaron Rodgers, Ben Roethlisberger, Drew Brees or Russell Wilson.

Furthermore, when your head coach is John Harbaugh, Andy Reid or Sean Payton, you’re going to find yourself firmly above average for the majority of the time.

As for the long-term below-average teams, the way out is also clear, even if it is ripe with fits and starts. Cleveland has taken four swings at the quarterback position in the top two rounds since 2011, while Jacksonville and New York are on their third. Tampa Bay, Miami, Cleveland and Buffalo all appear to have broken through with a combination of acquiring great coaching and good enough quarterback play (especially when grading on the rookie wage scale curve).

Exclusive content for premium subscribers

WANT TO KEEP READING?

Dominate Fantasy Football & Betting with AI-Powered Data & Tools Trusted By All 32 Teams

Already have a subscription? Log in

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.