In a pass-first game, priority No. 1 is to influence the decision-making of the one player who touches the football on every dropback. The pathway to the quarterback is impeded by a quintet of dancing bears, a term of endearment that still falls short of explaining how much is happening for the five men with their hands in the dirt. To maximize value in the passing game, offenses need to release all five receiving threats into a route, leaving offensive linemen to sort out all the potential havoc a defense can create without much in the way of help — in every season since 2018, NFL offenses have used five-man pass protection schemes more than 70% of the time.

Click here for more PFF tools:

Draft Guide & Big Board | Mock Draft Simulator

Dynasty Rankings & Projections | Free Agent Rankings | 2022 QB Annual

Player Grades

All pass protection schemes are sound, and in the era of the spread, offenses can get a general sense of which defenders can be pass-rushers. No rules in an offense’s execution are impossible to break, though, and that’s where all the film-grinding pays off for defensive coordinators. In three of the past four seasons, NFL defenses have generated pressure on 40% of passing snaps with a five-man protection scheme.

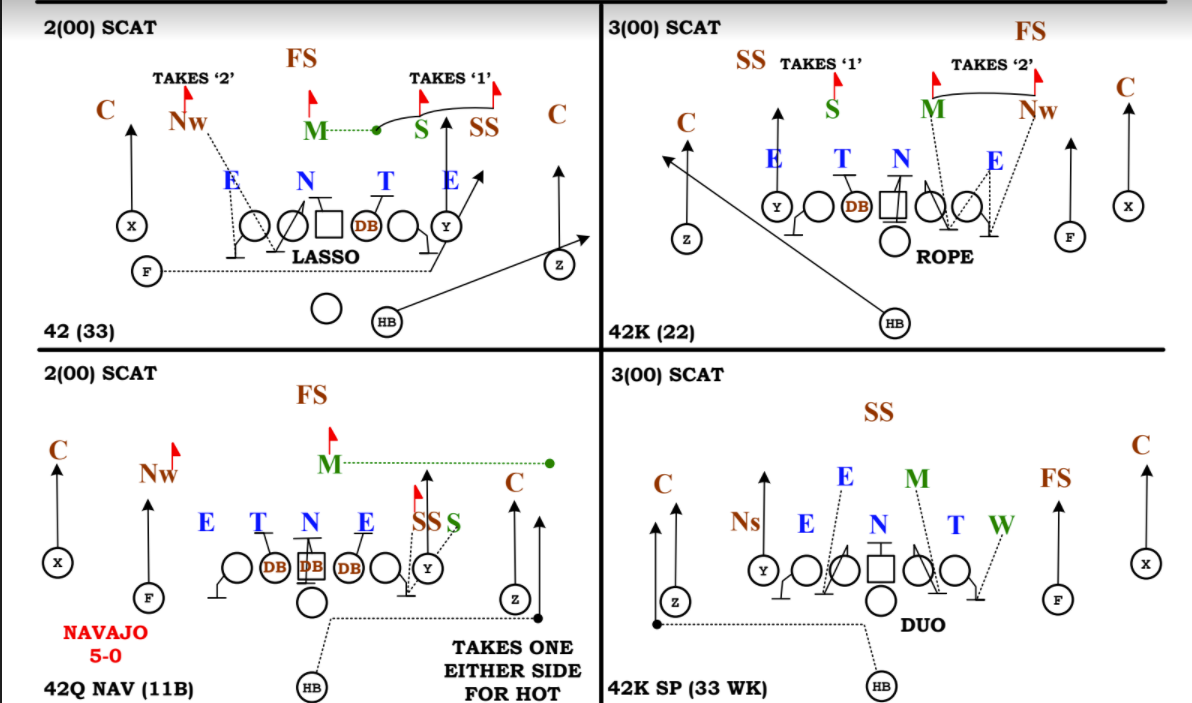

Defensively, there’s a tenuous give-and-take that comes with handling those five-man looks. For all the vertical and/or lateral strain that comes with covering all five players, there are only so many ways an offense can account for potential rushers and their pathways to the quarterback. In the example given above — “scat” protection — you can see that offenses want to execute what’s considered a “half slide.” In half-slide pass protection, the center declares which way he will turn (usually toward the player most likely to become the fifth pass-rusher), and he will work in tandem with the guard and tackle to the side of the turn. The guard and tackle away from the slide will block the most dangerous men, from inside-out. If there’s a defensive tackle between the backside guard and center, it turns into a four-man slide, with the understanding that if the rusher slants across the guard’s face, he will mirror the rusher and peel back with him.

There’s another important piece of intel in those diagrams, though, in the bottom-left square. When the center and guards are covered, offensive linemen will make a “5-0” call — meaning the center can’t set a slide in either direction, and all five linemen are blocking the most dangerous rushers. Often termed “man” protection, this is one of the few scenarios a defense can create that would dictate the terms of engagement.

Our takeaway: The key to getting to the quarterback, aside from having an elite pass-rusher, is to manipulate the center and force a 5-0 call, or generate pass rush away from the sliding protection. In not-so-simple terms, you want the pathway of your pass rush to turn man protections into half slides, and half slides into man.

In your typical even front structure, a defense can accomplish this by slanting the nose across the face of the center and blitzing/stunting a rusher into the area he vacated. With that pressure track, the hope is that the offense is in a four-man slide and the backside guard will mirror with the slant, leaving the backside tackle to choose who to block in a two-on-one situation. In the example taken from the Cowboys, linebacker Micah Parsons is attacking the face of the tackle and occupies him enough to give the edge an unblocked track to the quarterback.

Ideally, the offense would like the center to take over the slant, and have the guard turn back to find the most dangerous rusher remaining. The issue, though, is that the slide is set based on the “mike” (the potential rusher most likely to affect the center), and the center has to honor that defender until it's confirmed he’s not blitzing. If a defense can hold its disguise, it’s a tall task to communicate and respond to the defensive line movement in time.

A defense doesn’t have to rush five to generate value on these calls, either. A “creeper” concept — using an off-ball defender as the fourth rusher and dropping an on-ball defender into coverage — can force an offense into wasting sliding linemen. In this clip, Los Angeles converted pressure into a sack using the exact same pressure pathway it tried against San Francisco, in spite of dropping future Hall of Famer Von Miller into coverage.

It’s unrealistic to expect high-quality, unblocked pressure on a consistent basis. Defenses can get creative to layer the timing of the pass rush, so to speak. In the clip above, Dallas sets up an overloaded front (something defensive coordinator Dan Quinn used to great effect in Atlanta and Seattle previously), to force a four-man slide against this pressure track.

The nose tackle strikes the center before wiping back across his face, trying to get him to peel back with the stunt and turn a slide call into a man scheme. The design of this pressure track is foolproof, even though the nose’s job is unsuccessful: had the center peeled, Randy Gregory would have looped back into the A-gap unabated to the quarterback; if the center stays in the slide, the weakside end is stunting inside to pick the guard and tackle, allowing the nose to loop around unblocked. The benefit for Dallas is Gregory converting speed to power and blowing up the center before the nose can complete his pathway. Oftentimes, having the right Jimmy’s and Joe’s is better than being a chalkboard genius.

The real fun — for me, anyway — comes when defenses cover the center before the snap, getting the 5-0 look they want. Here, Parsons is walked up, and the Cowboys try a pass-off stunt to challenge Carolina to peel back into a four-man slide. Osa Odighizuwa runs his track too tight and collides with a teammate, but with Tarell Basham pressing a vertical pass rush, he squeezes the air out of Sam Darnold’s pocket.

When executed properly, the pass-off stunts paint a pretty picture for the defense. This time, Parsons is aligned over the guard and feigns an inside move before working for width. With the nose occupying the center, there’s no way for the offense to peel back into a four-man slide when Demarcus Lawrence loops off the center’s behind, and the quarterback has to throw hot despite having five linemen ready to handle five rushers.

Just like the Rams in an earlier example, defenses have some optionality in who rushes and who drops in these looks. Here, the Miami Dolphins are in a five-down front, and you can see the nose tackle tap his hip pre-snap. What’s being communicated to Brandon Jones is confirmation that the center is responsible for his rush, and Adam Butler is going to cross his face to open a rushing lane. Las Vegas properly gets back into a half-slide distribution, but with Jerome Baker dropping into coverage from the edge, the offensive tackle is wasted while Jones is unblocked.

Hammering home the idea of versatility, the Dolphins executed the exact same pass-off stunt Dallas used against Darnold and the Panthers, but they used Jones as the looping rusher and dropped Baker into coverage from a “mugged” alignment over the guard. The guard in front of Baker works back to one of the penetrating linemen, but there’s nowhere near enough time to get all three linemen to peel back into a four-man slide and pick up the blitzing Brandon Jones.

In particularly obvious passing situations, defenses can do even more to manipulate the protection by walking players up to the line of scrimmage. Miami uses a variation of its odd front in one clip and its max blitz look in the next. The schematic advantage at play: sending one more than the offense can block. Playing Cover 0 in the modern age is generally inadvisable, but the threat of max pressures is key to set up what former head coach Brian Flores does with the rest of this package.

With six defenders at the line of scrimmage, an offense can’t call a 5-0 protection — there’s no way to declare most dangerous across the board when each lineman has a threat on either side of him. The usual response in protection is to revert back into a half slide and make the quarterback responsible for beating an unblockable defender by throwing hot to an underneath route. At the goal line, where a quick throw would score points, Miami is still able to get a stop in this max pressure look by getting unblocked interior pressure against a four-man slide.

To try to protect quarterbacks from quick interior pressure, the offensive linemen may check into a “full slide,” meaning all five players will turn in the same direction and leave the weak edge unblocked for the quarterback to control with his arms and legs. Once an offense starts using full slides to pick up the potential rushers, Flores and Miami get right back into wasting players in the protection by running a “simulated pressure” — giving the impression that Cover 0 or a blitz is coming but rushing only four players and playing a base coverage. With the defensive line’s slant going in the same direction as the slide, Emmanuel Ogbah has a clear runway to Trevor Lawrence.

What happens in the trenches is underappreciated, oversimplified and done a disservice in our discussion of football — a curious occurrence given that the ball starts there, and the largest concentration of bodies can be found within a 10-yard radius of the center. While the limits of print work prevent me from explaining every angle of the interplay between pass protection and pass rush, this gives you an idea of how precise defenses can be in attacking an offense when it has a beat on how the quarterback will (and won’t) be protected.

Not a blade of grass, nor an ounce of energy, is to go wasted in the NFL. There’s a reason why coaches get in front of cameras and microphones and sound like they haven’t spoken to another sentient being in days — and you would, too, if you had to devote hours on end to scheming for success.

The film being studied, the processes of drawing and adjusting diagrams before erasing or saving, picking out mismatches and keying in on certain tendencies and indicators lead to 11 men flying to the football on Sundays. Controlled chaos, multiplicity and aggression, simplifying the complicated and every tired coach-ism between is borne out of the work done when lights are dim and projectors are running. Few or none of these play calls were invented in 2021, but the true genius of coaching is more about knowing when to call the play than knowing how to design it, and generating quick pressure takes a great deal of pressure off coverage players in handling five potential receiving threats.

Now you’ll know to shield your eyes when your favorite team’s center calls out “5-0” and to yell at the television to keep the running back in to protect when your favorite quarterback is running for his life.

Related content for you:

Building a defensive package with the top 2022 NFL Draft prospects: Defensive backs

via Diante Lee

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.