Six wide receivers heard their names called in the first round of the 2022 NFL Draft. That marked the third time that's happened since the new collective bargaining agreement in 2011, which implemented the rookie wage scale, and the second time in the past three years.

Wide receiver position value is reflected by metrics such as PFF WAR, and the surplus value of receivers on rookie contracts was already among the best of non-quarterbacks before the recent meteoric rise in top receiver contracts, so it makes sense that NFL teams are prioritizing the position. The easiest way to to get a wide receiver on a rookie deal, then, is to draft one in the first round of the draft.

But is this borne out in the data? Are receivers drafted in the first round that much more likely to be better than receivers taken later in the draft? We have ample reason to suspect this may not be the case:

- Anecdotally, many great receivers of the past decade were drafted in the second round, including A.J. Brown, D.K. Metcalf, Deebo Samuel, Michael Thomas and Davante Adams. And other stellar wideouts were taken even later, including Cooper Kupp, Stefon Diggs, Terry McLaurin, Chris Godwin and Keenan Allen.

- With more passing in college football due to the standardization of spread and Air Raid offenses in the 2010s alongside the proliferation of seven-on-seven at the high school level, younger receivers entering the league may have a smaller skill gap and thus perform similarly.

- As a corollary to the late George Young’s planet theory (there are only so many human beings on this planet who are big and athletic enough to play in the trenches in the NFL), wide receivers have a much more common body type. A boys high school AAU basketball tournament will have a surplus of young athletes who could grow into being between 5-foot-10 to 6-foot-3 and weigh 180-215 pounds. This means there is virtually no scarcity at the position and less pressure for NFL teams to draft a receiver early.

These arguments are compelling enough that it’s worth investigating the implicit claim behind drafting a wide receiver in the first round: Wide receivers drafted in the first round perform better than receivers taken later in the draft. To limit the scope of our study, we will be focusing on the difference between first- and second-round receivers.

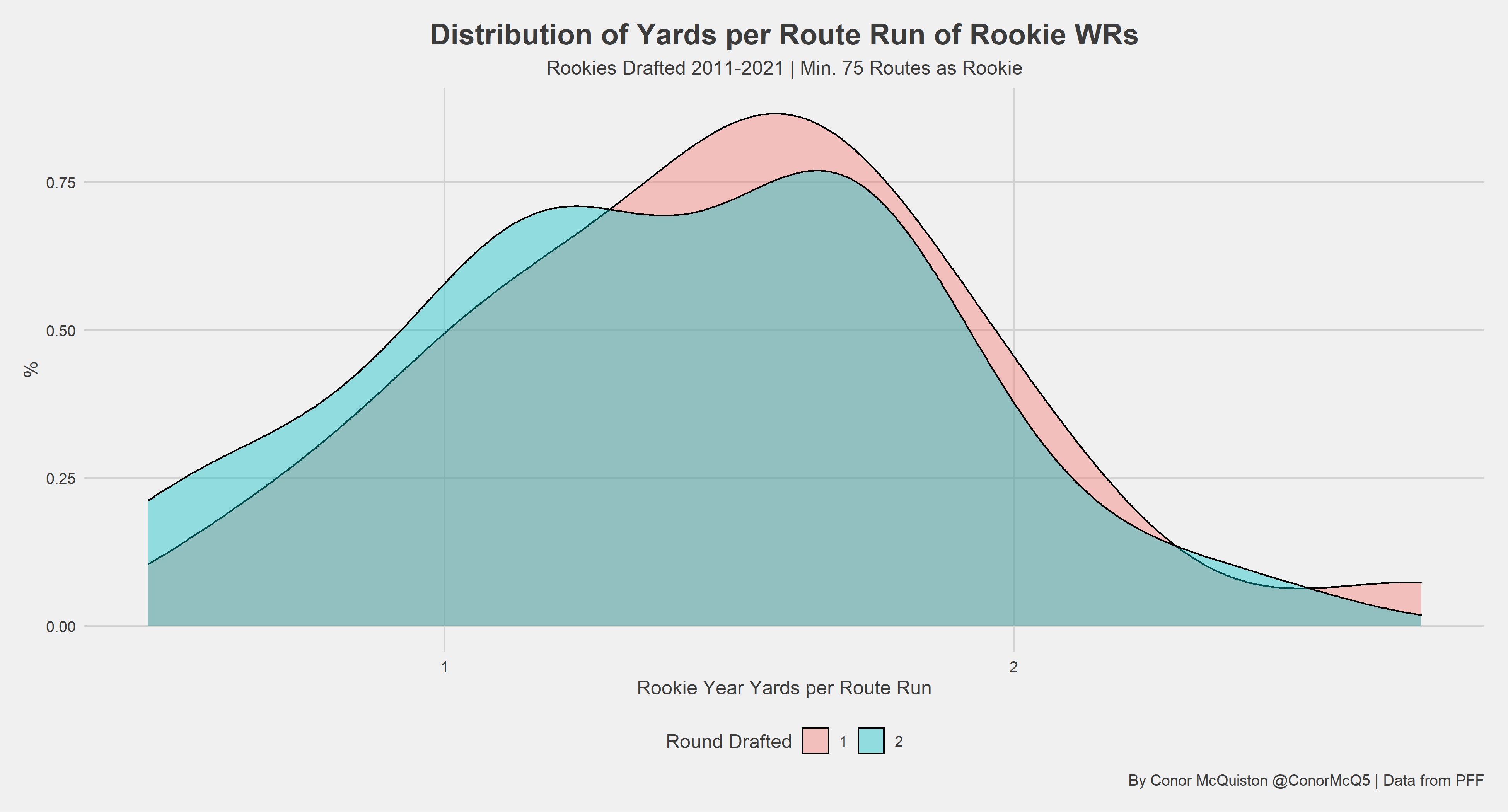

We will use yards per route run as our evaluation metric for wide receiver production. As in any case of using a single metric, this is a simplification and ignores major differences in player roles. However, for our purposes, it works as a catch-all efficiency metric. We’ll begin by observing the distribution of yards per route run of rookie receivers.

The distribution is extremely similar, but the distribution for receivers drafted in Round 1 is shifted to the right of receivers drafted in Round 2. This implies that, while there may be individual second-round receivers who outperform individual first-round receivers, as a collective the first-round receivers tend to outperform the second-rounders. We get further confirmation of this point by bootstrapping the mean of the two distributions.

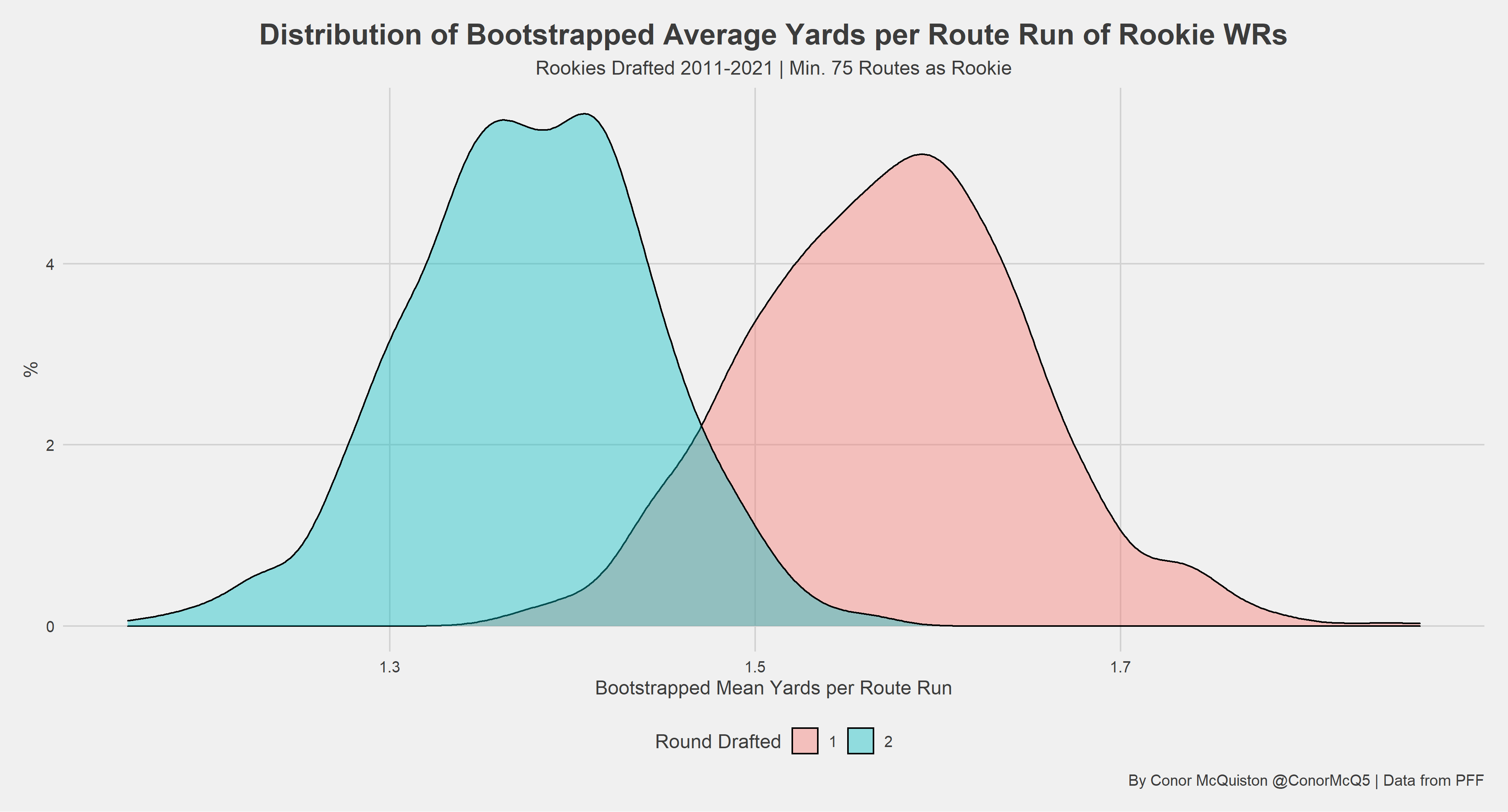

Upon bootstrapping the results 1,000 times, we see that the means of the two distributions are significantly different. These more robust estimates show that, on average, first-round wide receivers have 0.21 more yards per route run than second-round receivers — 1.58 YPRR versus 1.37 YPRR — in their rookie season. This is an unsurprising result, as we would expect first-round receivers to be viewed as safer options and thus have more early success.

This does not, however, account for the fact that NFL teams draft players for more than just their rookie year, looking to develop them into perennial stars. PFF's Timo Riske has found evidence that wide receivers take a single year to get acclimated to NFL football. With all rookie contracts being at least four years long, it is safe to assume NFL teams expect by Year 3 that receivers are as good as they will be for the rest of their NFL career. So, it is worthwhile to look at the difference in performance between receivers three years into their career.

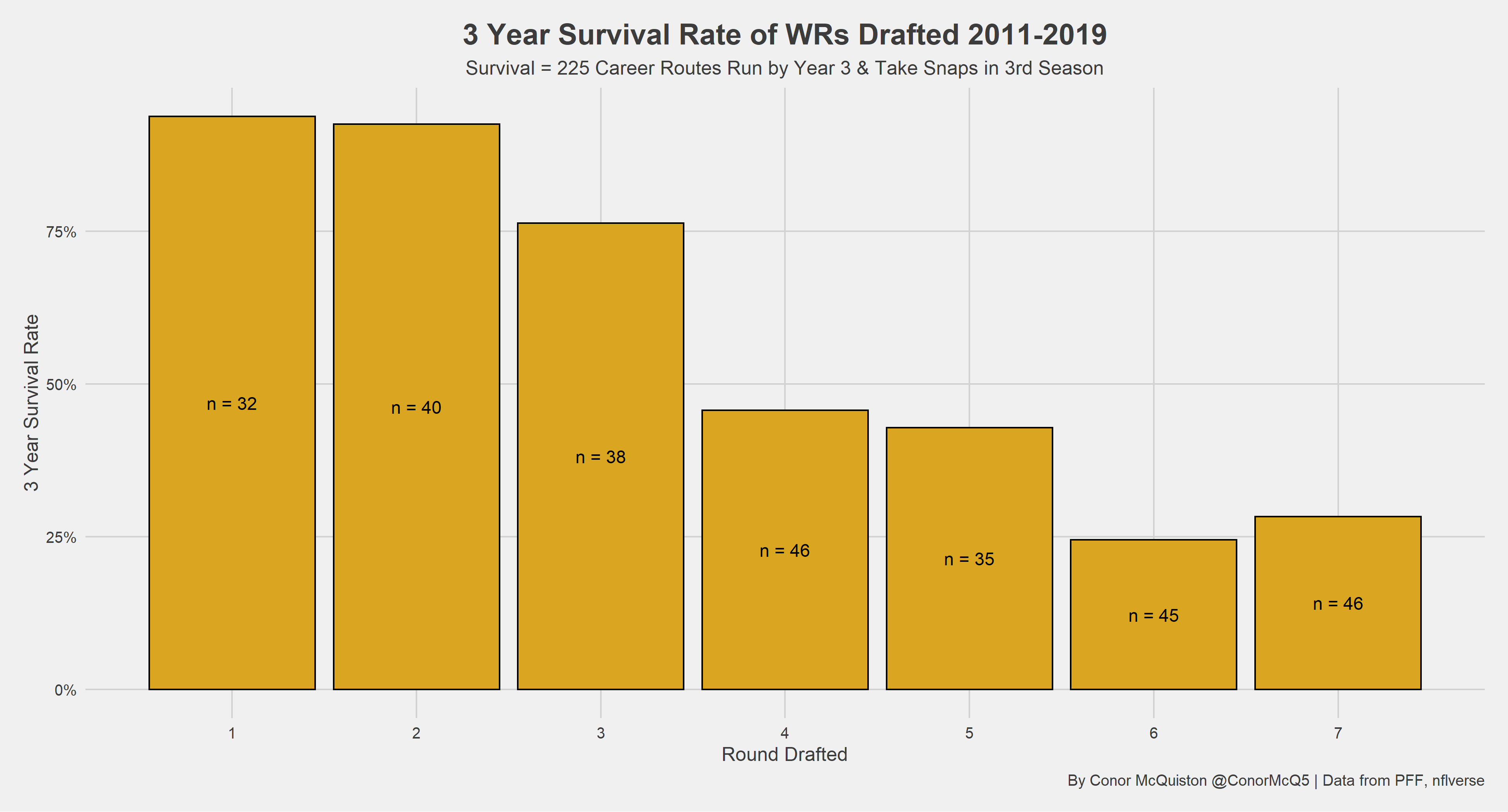

Looking several years into a player’s career inherently creates survivorship bias — especially after a minimum route threshold is established to weed out potential outliers due to small samples. The established thresholds are small enough, working out to less than five routes a game, that they should functionally help determine whether a player is still on a roster, but it is still worthwhile to explore.

Under this threshold, we observe minimal impacts of survivorship bias for first- and second-round receivers, although it gets much more drastic in the later rounds. First- and second-rounders survive three years into their NFL careers at rates approaching 95%, and while first-rounders do survive at a slightly higher rate (93.8% vs. 92.5%), it is an inconsequential difference for practical purposes.

Receivers taken in the first two rounds are also given extra chances to succeed at least up to their third season. This is a low bar for what qualifies as surviving, but having this low bar prevents the possibility of introducing even more survivorship and selection bias in setting the route threshold at, say, the number of routes a starter would run.

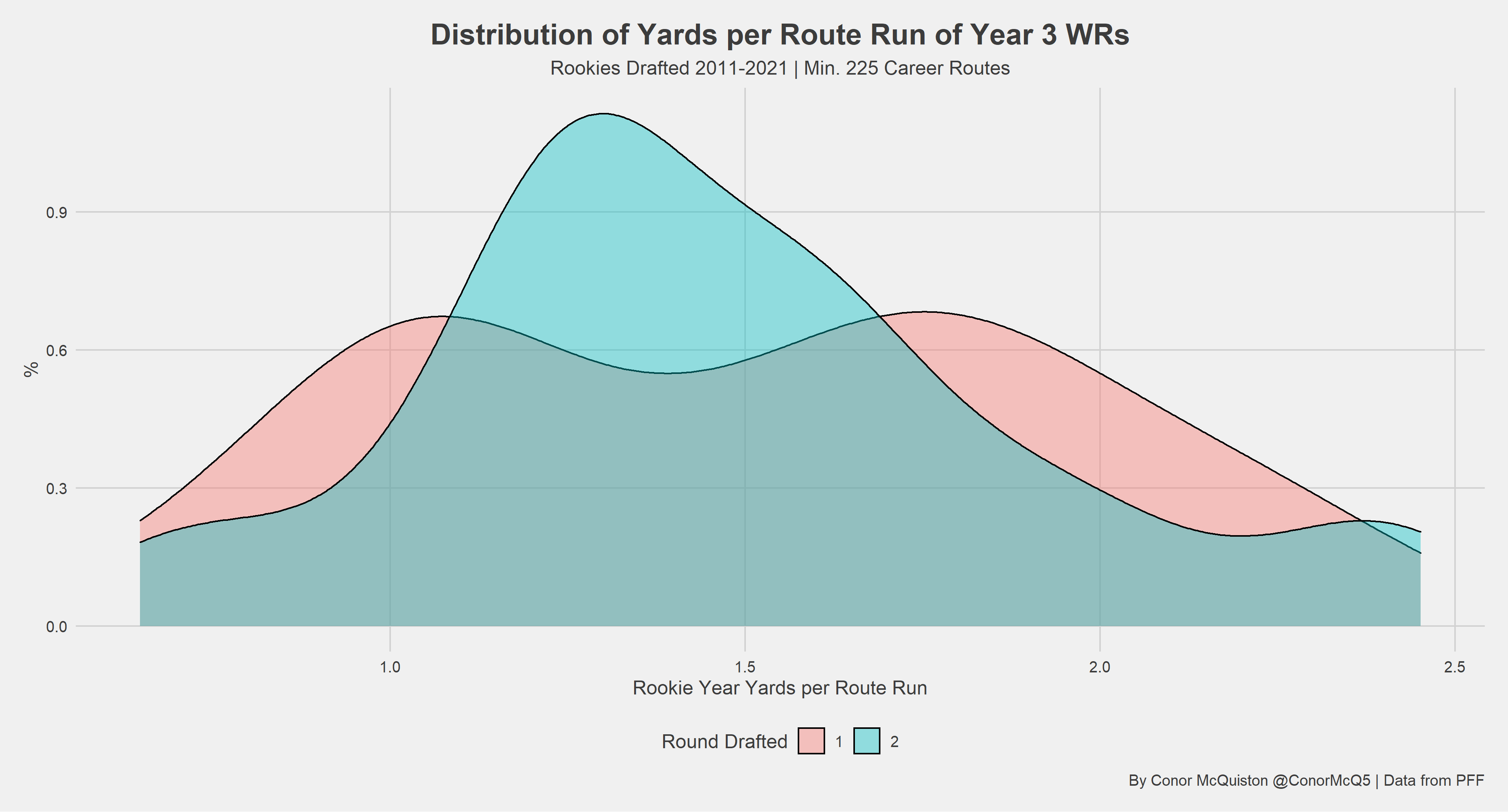

With the survivorship bias accounted for, which for our purposes is minimal, we can look at the distribution of career yards per route run for receivers by their third season who were drafted in the first and second rounds.

It is not obvious which group does better on average. Interestingly, the first- round receivers form a nearly bimodal shape that has both more high-end and low-end performers than second-round receivers. A potential interpretation of this data is that if both a first- and second-round receiver fail, the first-round receiver is likely to fail harder. Or at the very least, less efficient first-round receivers will be given more chances than inefficient second-round receivers.

Players taken in the first round are also more likely to reach elite levels of production, generally considered to be 2.0 YPRR or more. Once again, we’ll bootstrap the means of the distribution to get a better idea of which group does better on average.

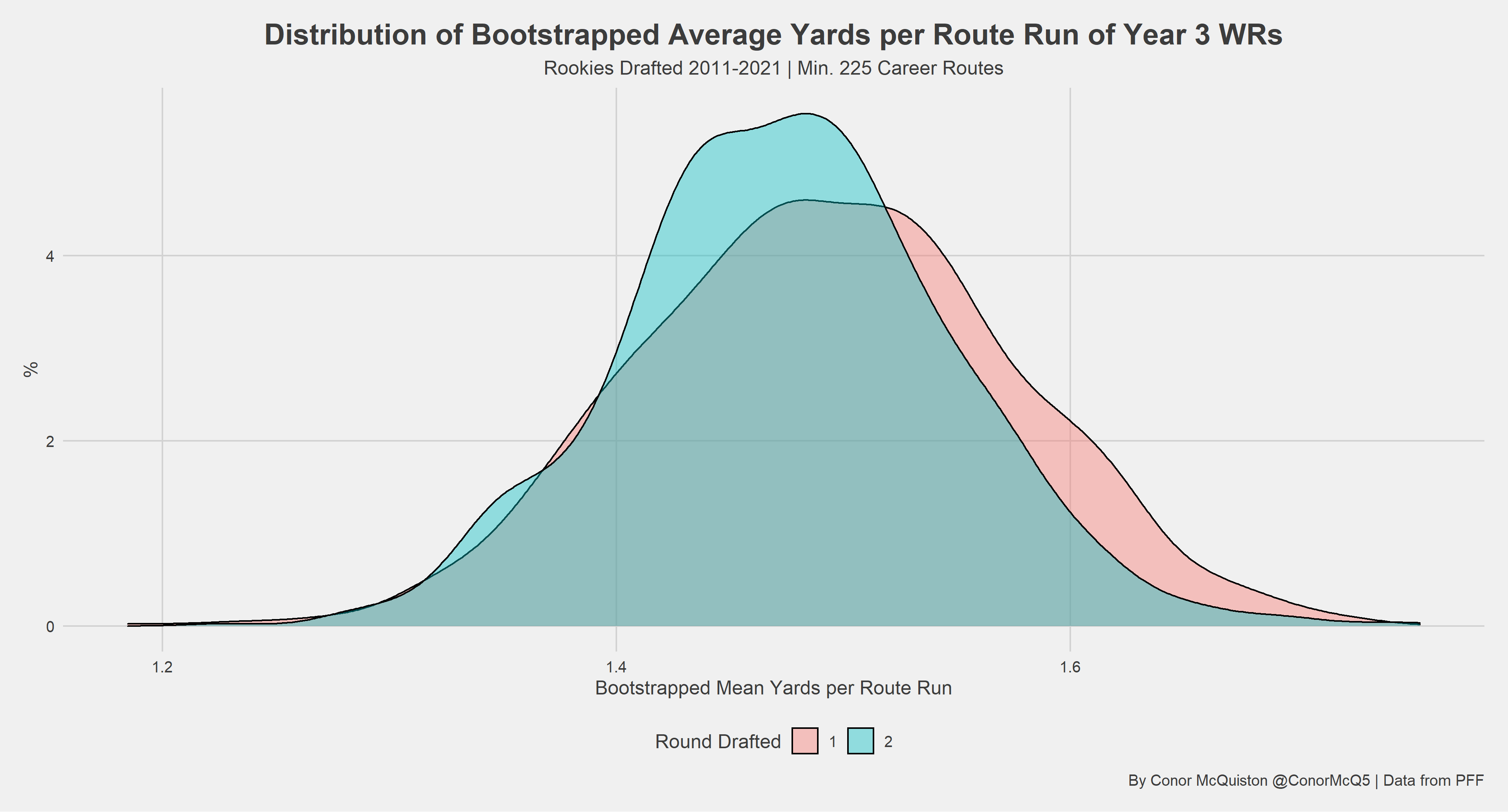

The results of the bootstrap are extremely similar. They are statistically significantly different, although the first-round receivers barely perform better on average, only having a 0.01 YPRR improvement over second-round receivers (1.49 vs. 1.48).

Do first-round receivers outproduce second-round receivers by their third season? In a literal sense, yes. We have statistical evidence that, on average, the former barely produces better than the latter. The complexity of the issue arises in that the difference for practical purposes can be argued to be negligible. Additionally, when considering the whole distribution, the more accurate statement seems to be, “First-round receivers who bust are on average worse than second-round receivers, while first-round receivers who don’t are on average better than second-round receivers.”

It is outside the scope of this study to differentiate busts from hits in first-round receivers, but upon inspection, most of the “busts” can broadly be categorized as speed receivers (John Ross, Phillip Dorsett, Corey Coleman) or gadget players (Cordarrelle Patterson, Tavon Austin). This is not the case for the receivers who“hit.” This may suggest a certain kind of first-round receiver is more likely to bust, although that's strictly speculation. A very tenuous, actionable observation from this is that when given the option between selecting a speed or gadget receiver in the first or waiting to take a receiver in the second, the latter may be a safer option.

To summarize: In a receiver’s rookie year, those drafted in the first round on average outperform those drafted in the second round. However, once receivers are several years into their careers, the differences between the groups nearly converge. By this point, the first-rounders are nearly evenly split into groups that, on average, outperform second-rounders and those that do not. However, there is slight speculative evidence that suggests waiting to draft a receiver in the second round is safer than selecting a specific type of receiver in the first.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.