• Click here for the introduction article to this series on quarterback traits.

• Scramblers versus non-scramblers: Scrambling quarterbacks depend far less on their environment compared to non-scrambling quarterbacks.

• What the data says: True scrambling production is a stable skill that can better predict performance under pressure.

Estimated Reading Time: 12 minutes

The next part of the quarterback traits series is all about scrambling, endemic to understanding and predicting the modern NFL. But part of the problem in studying scrambling is that quarterback scrambles, as defined on the stat sheet, present a classic selection bias problem. By definition, a scramble must gain yards — as it otherwise would be charted a sack. However, using PFF charting data allows us to maneuver around this problem.

PFF charts not only the result of the play but also the process. Did a quarterback attempt to scramble and get sacked? Did he start to scramble and realize he has an open man to throw to? In PFF charting terms — as we will use throughout this article — “scrambling” doesn’t necessarily mean a quarterback runs past the line of scrimmage. Rather, a scramble refers to any time the quarterback begins the process of scrambling, regardless of whether he reaches the line of scrimmage, is sacked or attempts a pass. Let's call these “true scrambles.”

We will dive into this trait of true scrambles, which encompasses skills such as pocket awareness and using one's legs to avoid sacks and gain yards on the ground. We will also study some of the trade-offs of scrambling and how scrambling interacts with other facets of the game to allow us to better understand and predict future production.

Here is an example of what each looks like on the film: a Justin Herbert true scramble pass, a Justin Fields true scramble run and a Russell Wilson true scramble sack.

Scrambles and Pressure

As you can see from the film, most of the time a quarterback scrambles it is either to avoid the impending rush or to escape already existing pressure. Scrambling is very closely tied to pressure. Nearly 75% of scrambles are also charted as pressures, and many of the 25% not charted as pressures likely would have been had the quarterback not scrambled in anticipation of pressure.

In establishing base rates, then, we should compare true scrambles to play under pressure rather than the full subset of plays. And scrambles are nearly two times more effective from an expected points added perspective as plays under pressure (-0.15 EPA vs. -0.32 EPA). But perhaps more important is that a quarterback's true scramble EPA is twice as stable year-over-year as EPA under pressure.

| Metric | YoY R-Value (Stability) |

| Pressure EPA | .19 |

| True Scramble EPA | .40 |

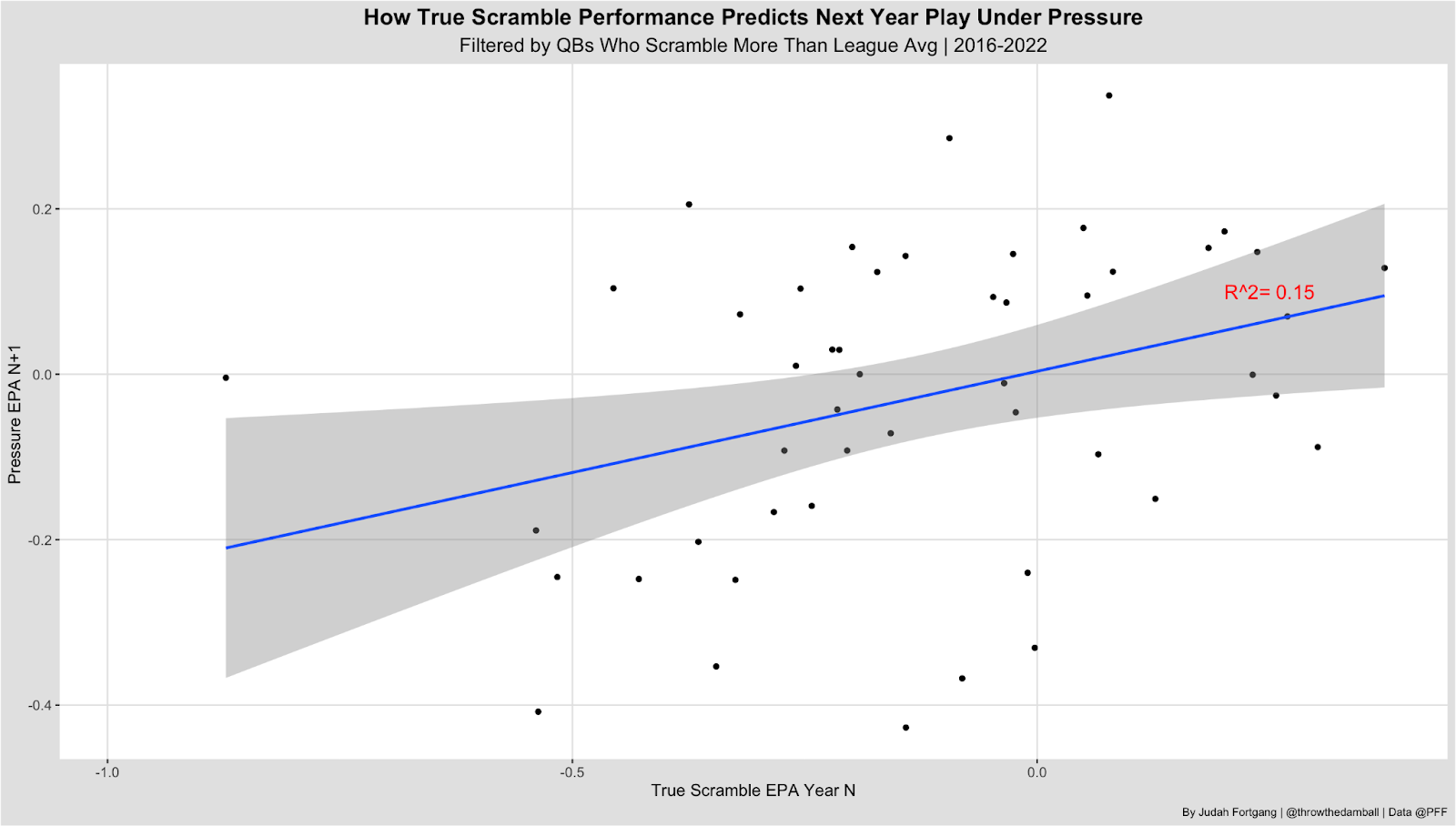

Better yet, performance on true scrambles does a far better job of predicting next year's EPA under pressure than the previous year's EPA under pressure. The previous year's true scramble EPA has an R-squared value of 0.10, meaning it captures 10% of the variance of next year's pressure EPA. The previous year's pressure EPA captures only 1.5% of the variance of next year's pressure EPA.

And if we filtered our sample to quarterbacks who scramble more than the league average, that R-squared number jumps to 0.15, compared to 0.03 for pressure. This relationship holds as the threshold for scrambles increases.

What this means, essentially, is that scrambling, which is stable year-over-year, is a very good predictor of next year's EPA under pressure — taking an otherwise noisy area and stabilizing it.

Especially for quarterbacks who scramble a lot, play under pressure should not be seen as necessarily unstable and noisy but, rather, as a reflection of how good a scrambler they are. And according to this research, we can consider that a stable trait.

It is also worth noting that, despite accounting for only about 15% of all passing plays, true scrambles are among the highest-leverage plays in a game. On true scrambles, using raw PFF grades, a quarterback plays at expectation only 35% of the time. On non-scrambles, quarterbacks play at expectation 60% of the time, suggesting there is more differentiation among quarterbacks when scrambling compared to not.

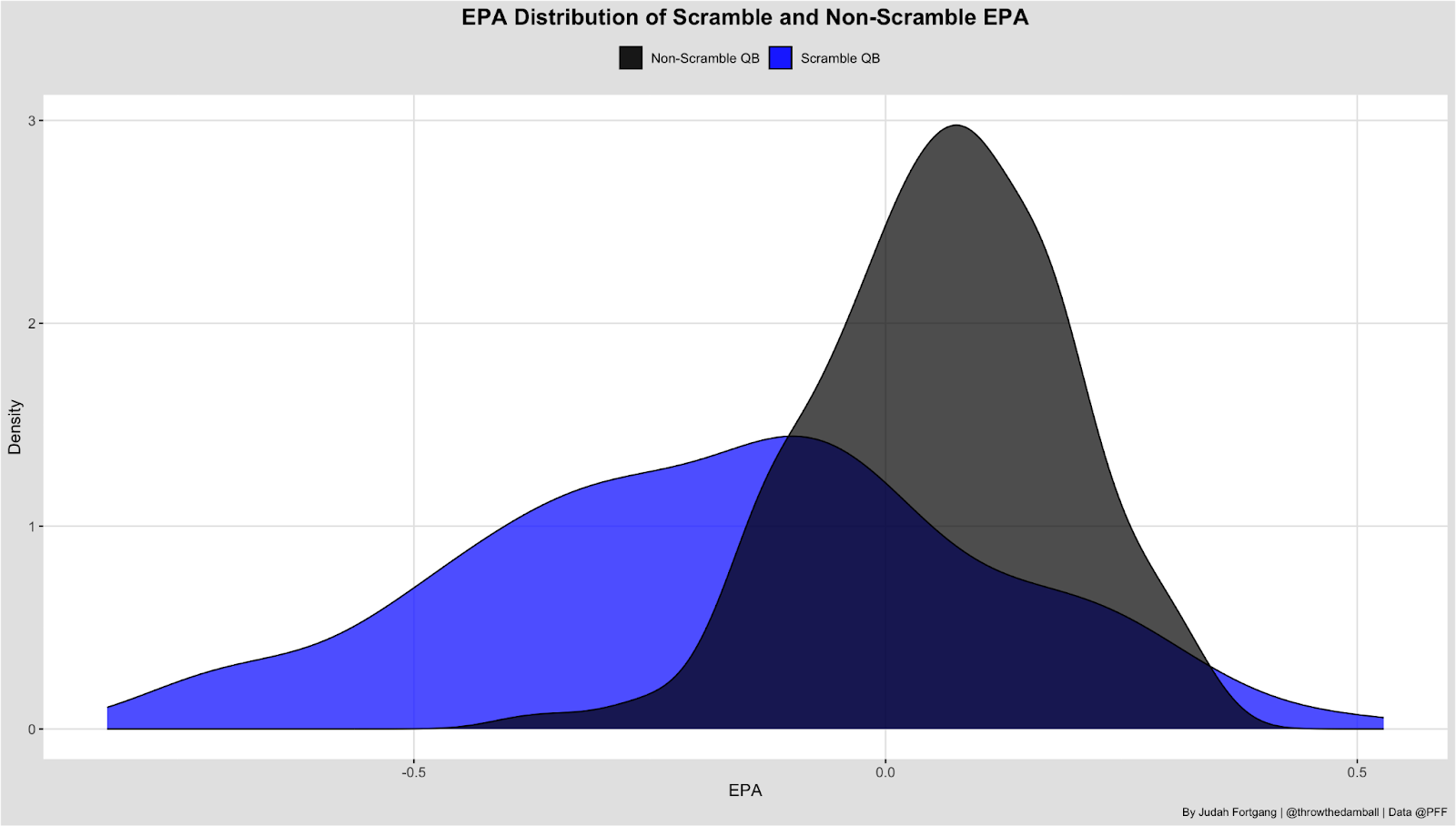

Consider this EPA distribution chart where the tails for scrambles (blue) are far wider than for non-scrambles (black). This demonstrates the importance of scrambles despite their low frequency.

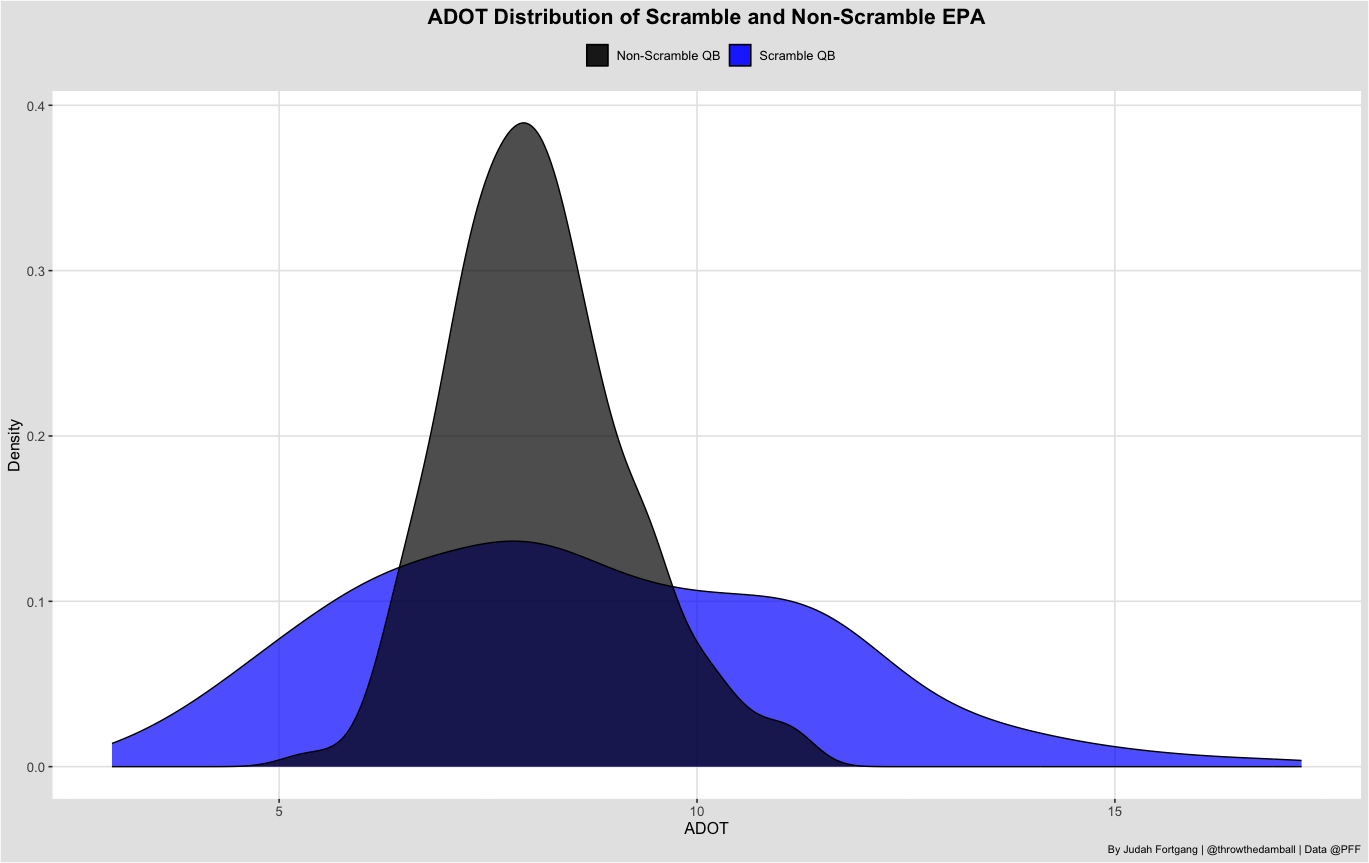

The styles by which a quarterback plays also have wide distributions. Again, scrambles are plays outside of structure and scheme where a quarterback's talent and style shine through more so than in other contexts. Let's look at average depth of target on true scramble passes as an example of how scrambling helps a quarterback's style shine through.

What we see here is that on non-scrambles, all quarterbacks throw, on average, roughly within five yards of each other. On true scrambles, that range widens to about 12 yards. If we looked at time to throw, sacks or any other feature, we would have the same distribution. With that in mind, let’s take a look at who was most aggressive in 2022 on their true scramble passes.

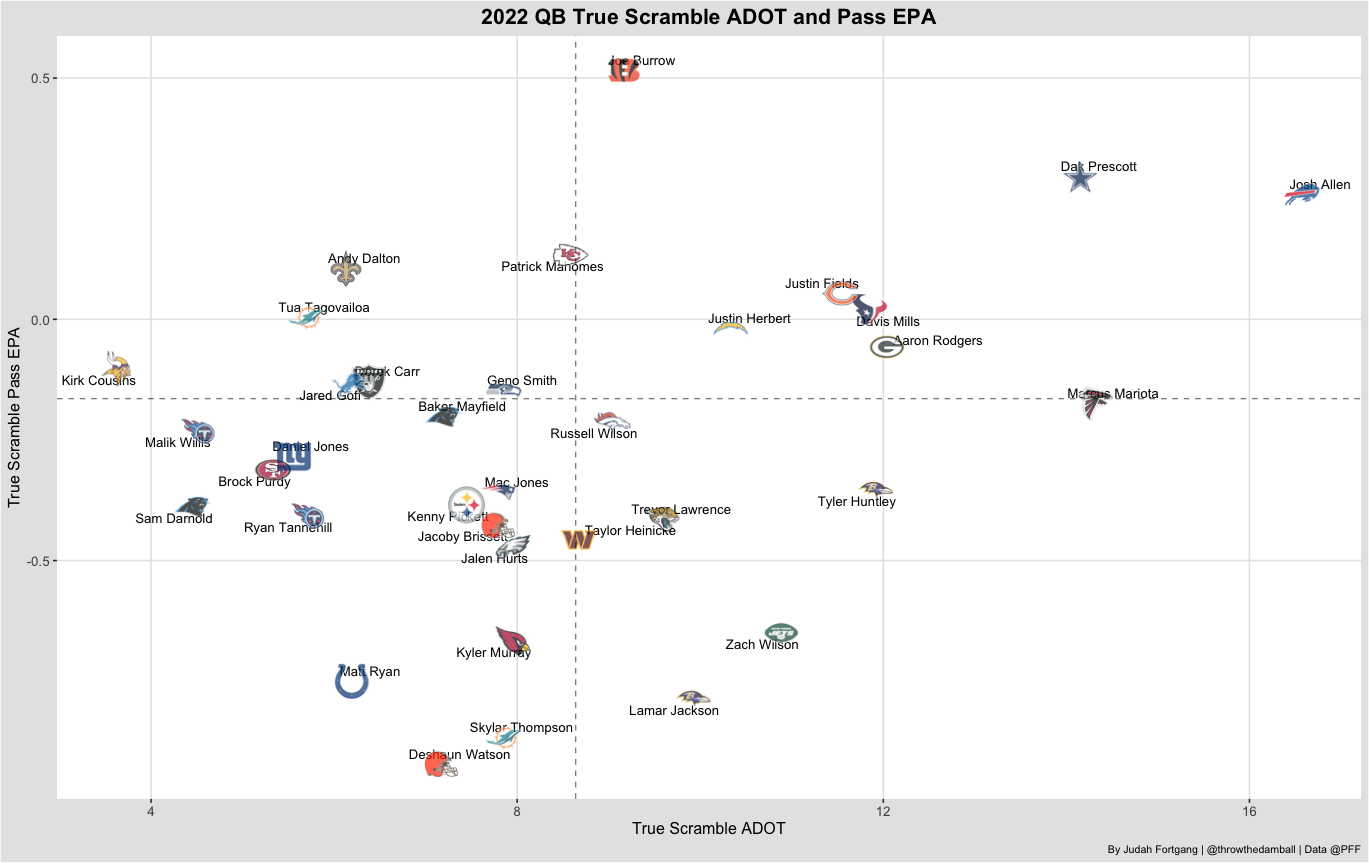

It should come as no surprise that Kirk Cousins and Josh Allen bookend the X-axis as the least and most aggressive quarterbacks, respectively, on true scramble passes. But more generally, this chart suggests quarterbacks like Cousins, Ryan Tannehill and Derek Carr have uber-conservative scramble styles dedicated to limiting negative plays.

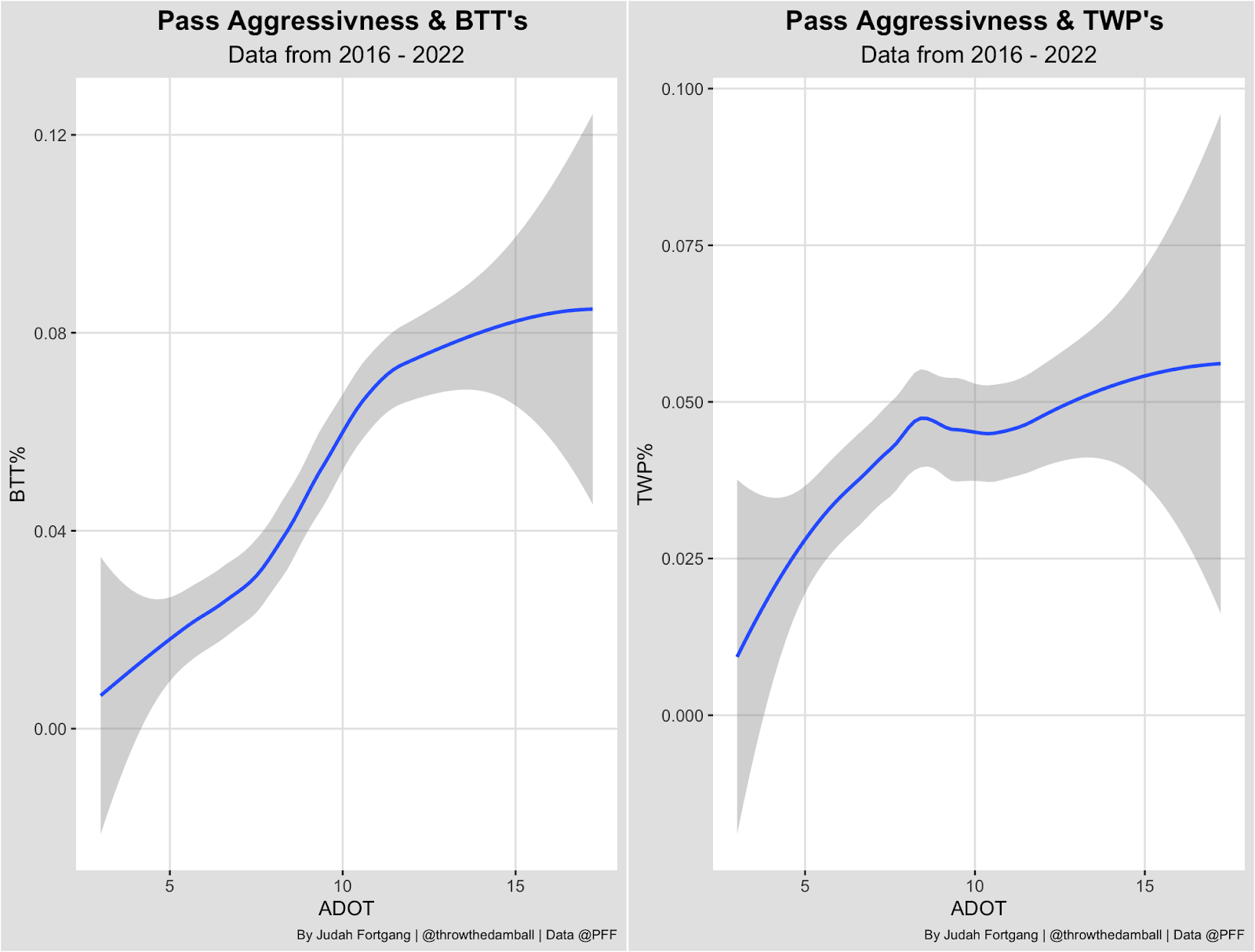

Throwing shorter passes lowers the chances of making a turnover-worthy play, though at the cost of having almost no chance of making a big-time throw.

But for Josh Allen, Dak Prescott and Justin Herbert, scrambles present an opportunity to lean into their aggressiveness and their talent, which can lead to some of their highest-upside outcomes. The quarterbacks who can engineer their own throws then, effectively, have more opportunities to gain big chunks, whereas the conservative types need a specific environment — a clean pocket with open receivers — to maximize their abilities.

Understanding that scramble styles have wide distributions and results, we can begin to see which quarterbacks performed best on true scramble sacks, passes and runs.

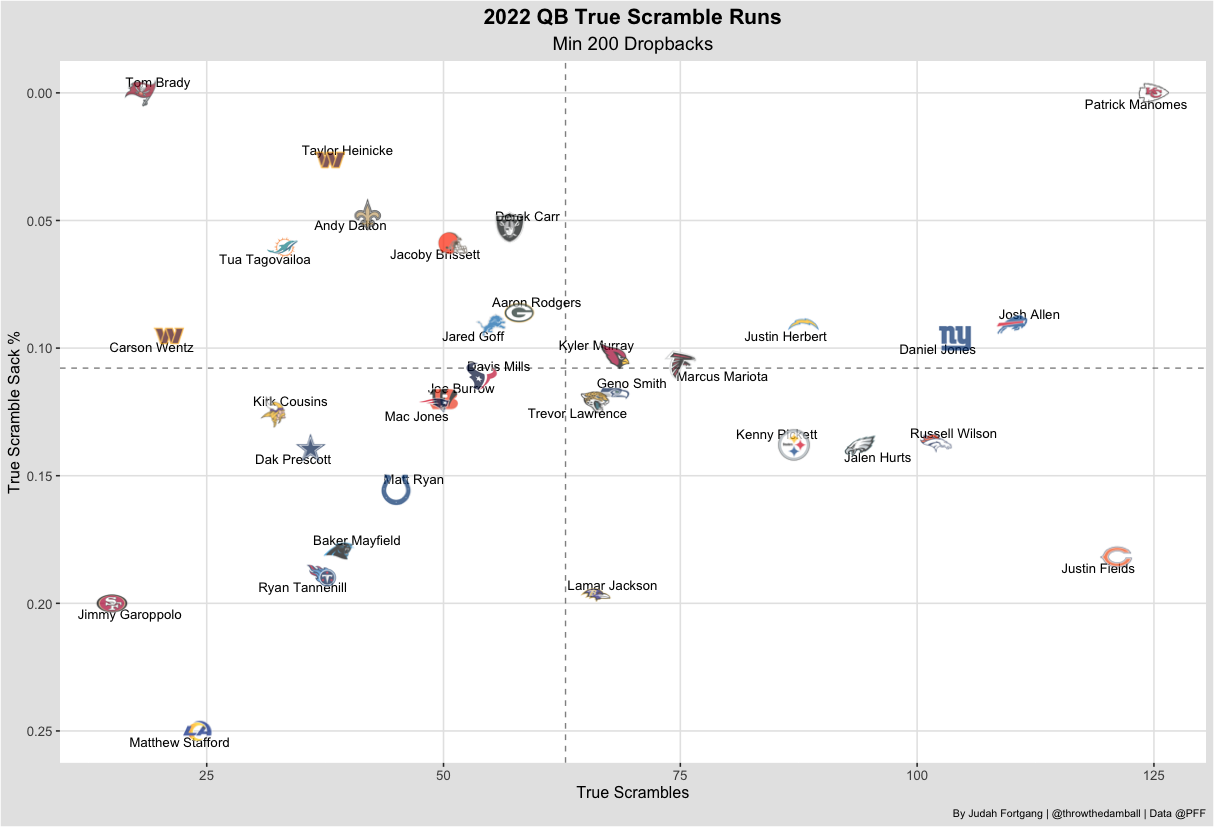

The above chart is a look at the frequency with which quarterbacks scrambled and their ability to avoid sacks. Patrick Mahomes, of course, breaks the chart with zero sacks taken despite leading the NFL in scrambles.

Even some of the best scramblers take plenty of sacks, though — and for some, that’s a worthwhile trade-off. Dak Prescott and Joe Burrow can deal with high sack rates because their holding onto the ball — the primary cause of the sacks — is also correlated with waiting to find open receivers further downfield. But Kirk Cousins and Ryan Tannehill’s high sack totals kill their efficiency, as it does not come with the trade-off of aggression. Tom Brady had a remarkable ability to avoid sacks by getting rid of the ball quickly, which was likely a beneficial trade-off with an aggressive play style, given his lack of mobility.

Let’s take a look now at scramble runs.

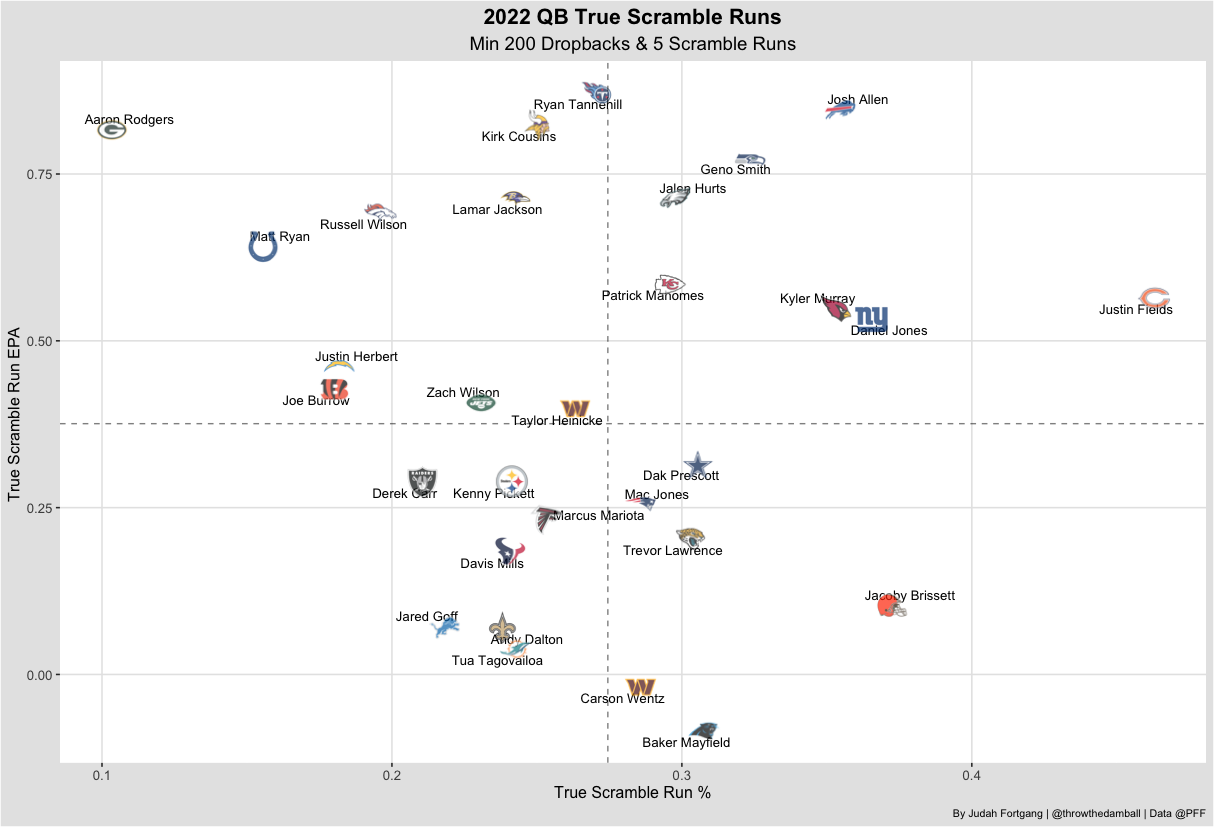

This chart is certainly dealing with some small sample sizes, but it nonetheless seems to be in line with how one would define good scramblers in the traditional sense.

We should now have a good sense of player scramble styles as we dive into our next section.

Interactions

Like anything in football, to truly understand how a certain skill manifests, we must look into how it influences and interacts with other facets of the game. Can effective scrambles neutralize a good pass rush? Beat a good coverage unit? Do they require good offensive lines?

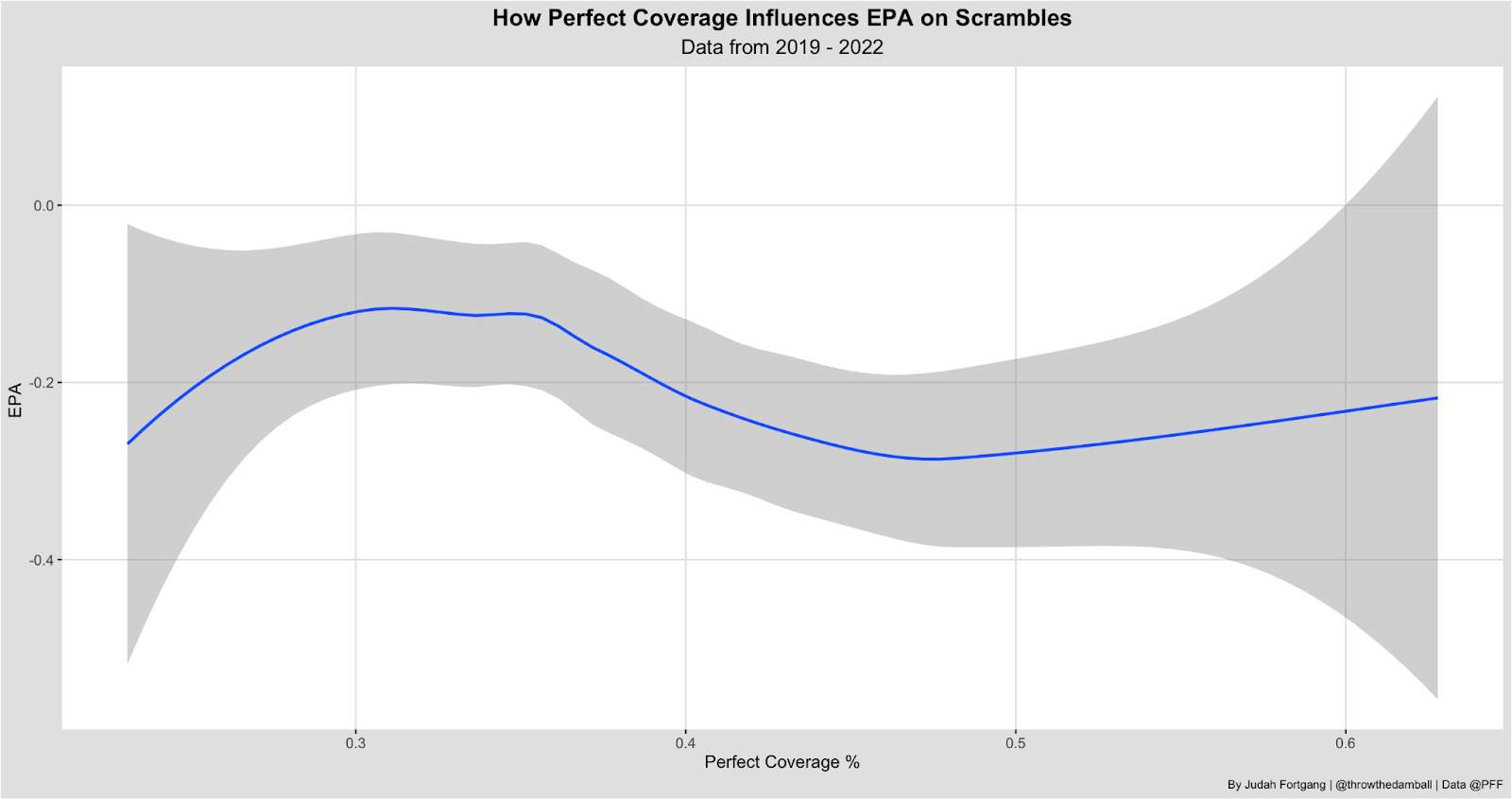

Defensively, we can use perfect coverage as a proxy for team-level coverage to see how coverage influences the effectiveness of a scrambling quarterback.

This curve suggests that as the perfect coverage rate increases — or as the quality of the coverage improves — there is only a small downturn in efficiency for scramblers. This curve holds true even if we filtered to only pass plays, suggesting this is not simply a product of quarterback scramble runs.

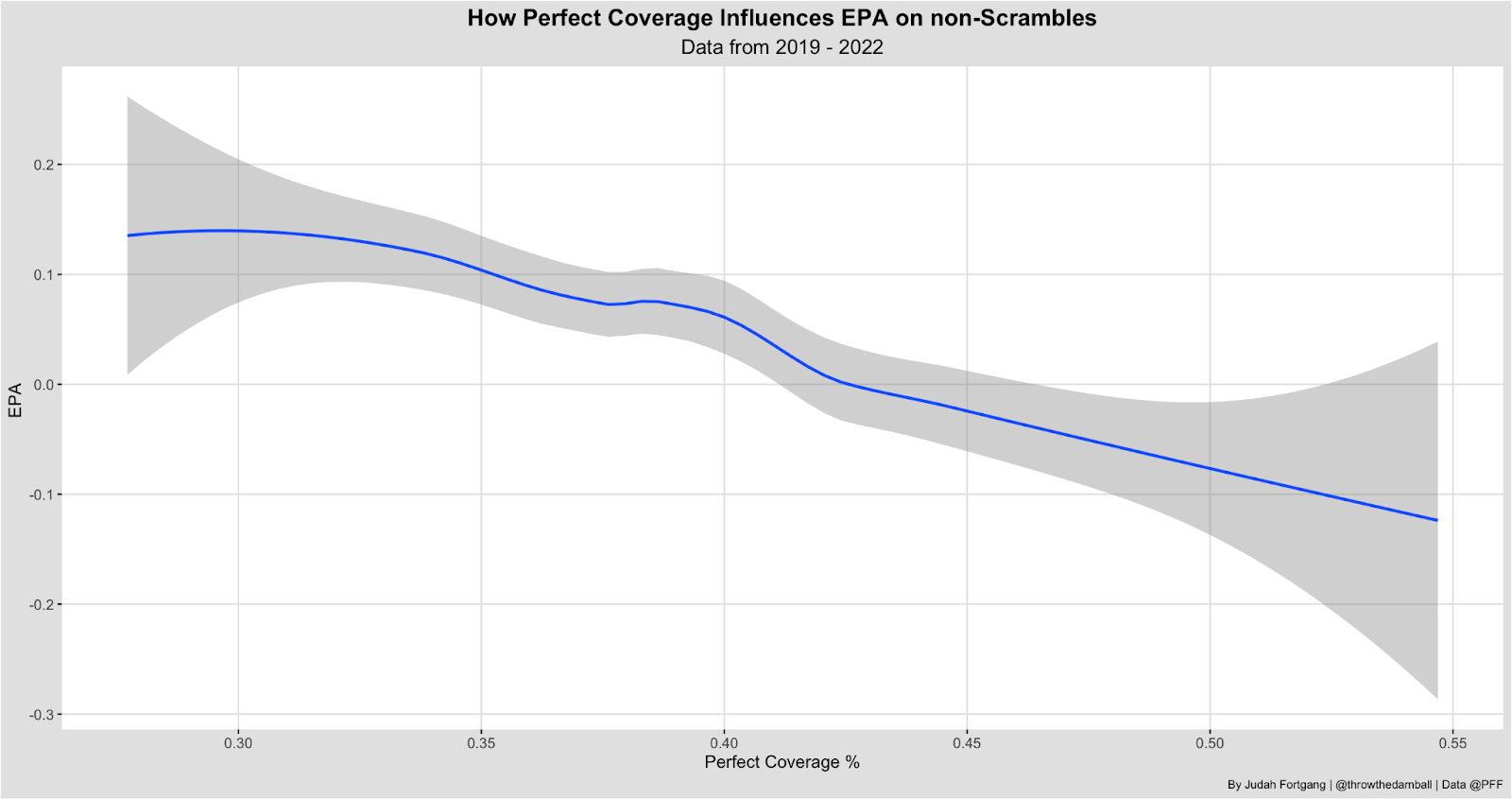

If we compare this to non-scrambles, we would see a completely different relationship. The rate at which a coverage unit improves — following the X-axis — corresponds with a huge dip in production for a quarterback not scrambling (Y-axis). Secondary matchups matter far more for offensive production when a quarterback is not scrambling as opposed to when they are scrambling.

Can a scrambling quarterback mitigate a good rush? It depends.

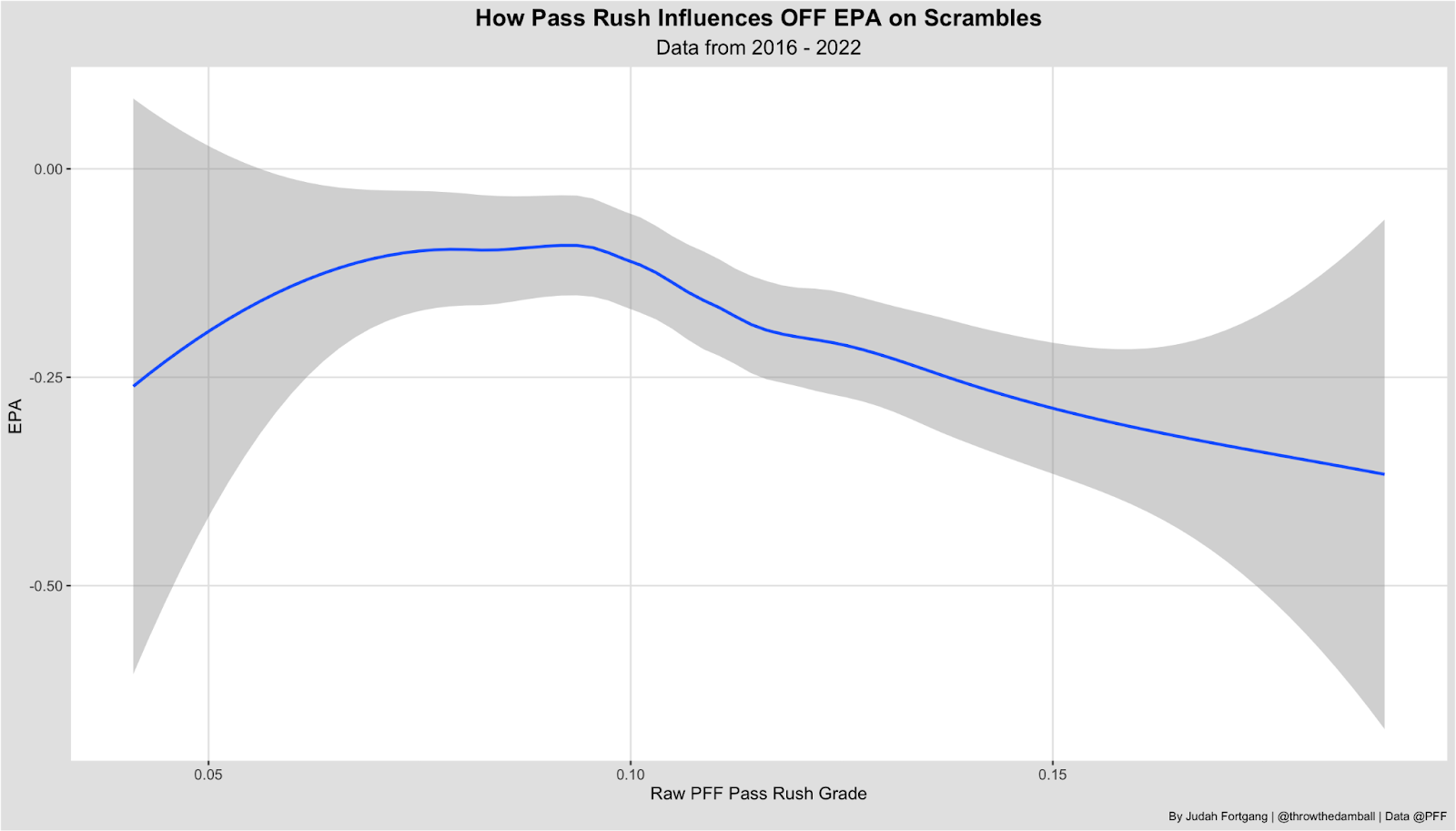

Unlike the secondary, for which an increase in quality does not hinder scrambling production, this curve would suggest that a stronger pass rush (X-axis) does indeed diminish scrambling production (Y-axis).

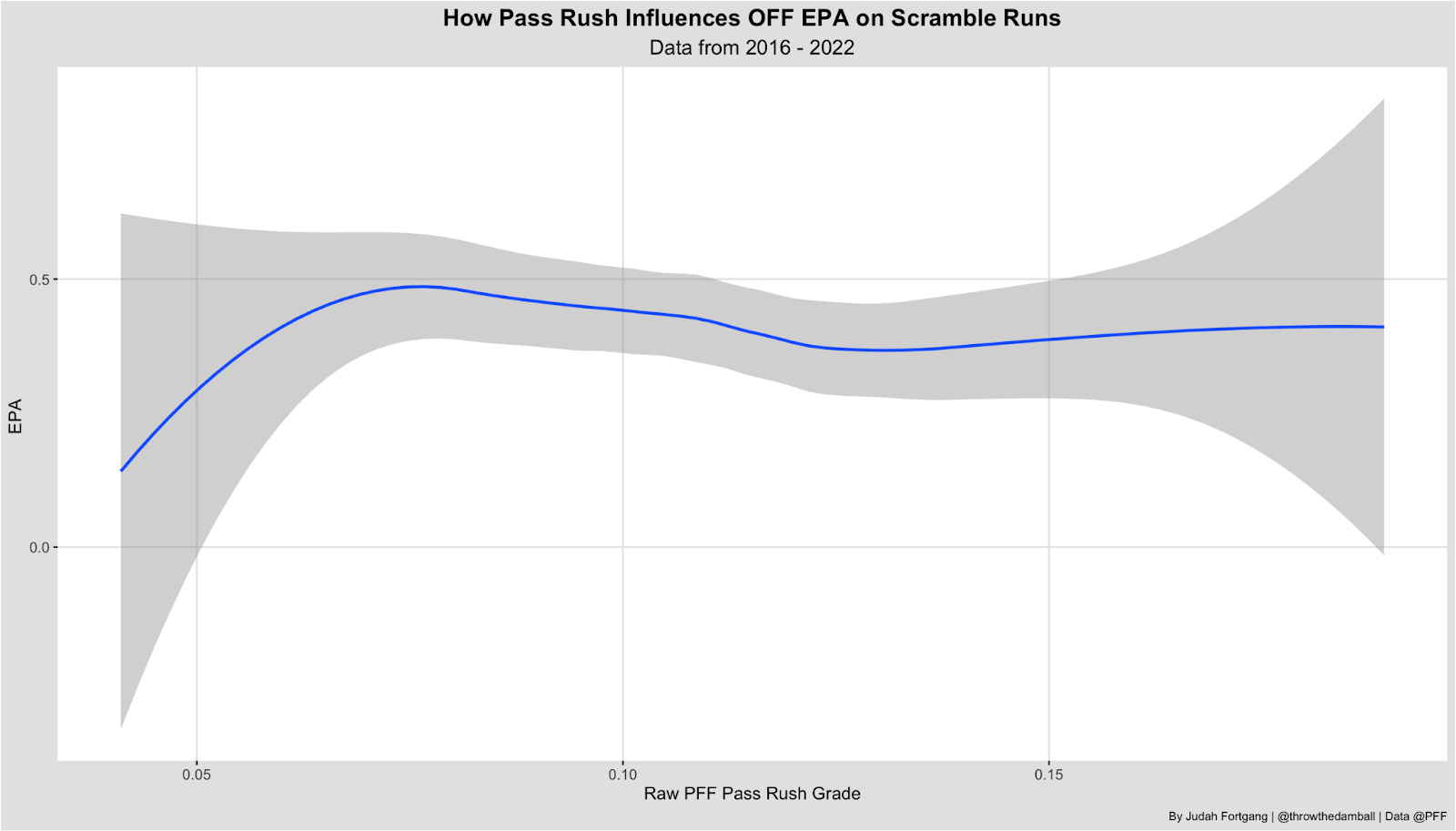

But further context is needed here. If we break the scrambling curve into runs and throws, scramblers who run mitigate the presence of a strong pass rush. As you see, the curve remains relatively flat even as the pass-rush quality increases on the X-axis.

This means that a player who derives their scrambling value from runs, such as Justin Fields, is much less prone to a matchup with a ferocious pass rush than a player who derives their scrambling value from throws and avoiding sacks, such as Dak Prescott.

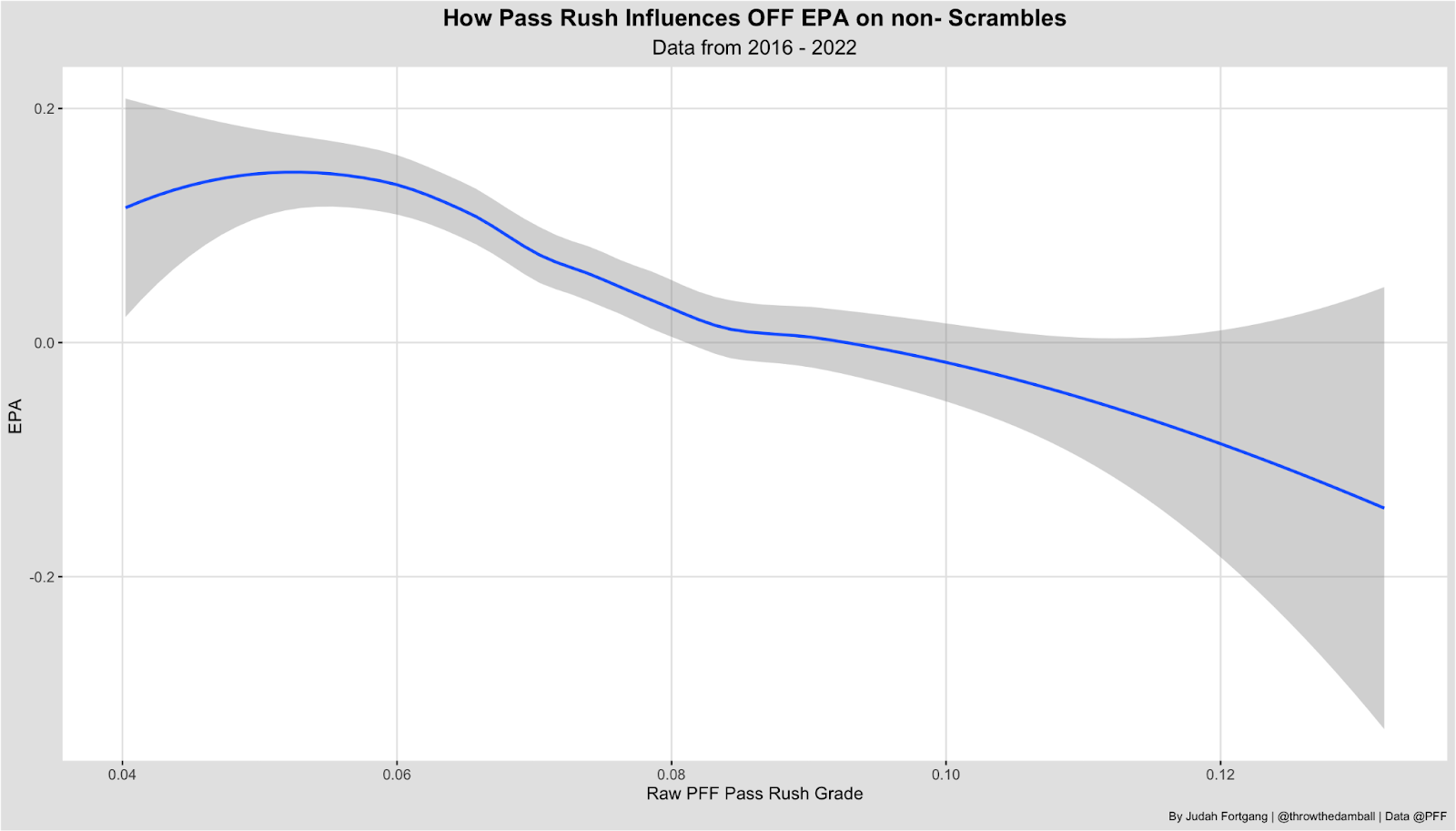

On non-scrambles, it should come as no surprise that an enhanced pass rush greatly reduces the chance of success for an offense and quarterback. But we should also note the slope of the curve. An increase in pass-rush production causes offensive production to tank on non-scrambles, whereas on true scrambles (two charts above) the curve has a more gradual and flatter downturn.

Offensive Interactions

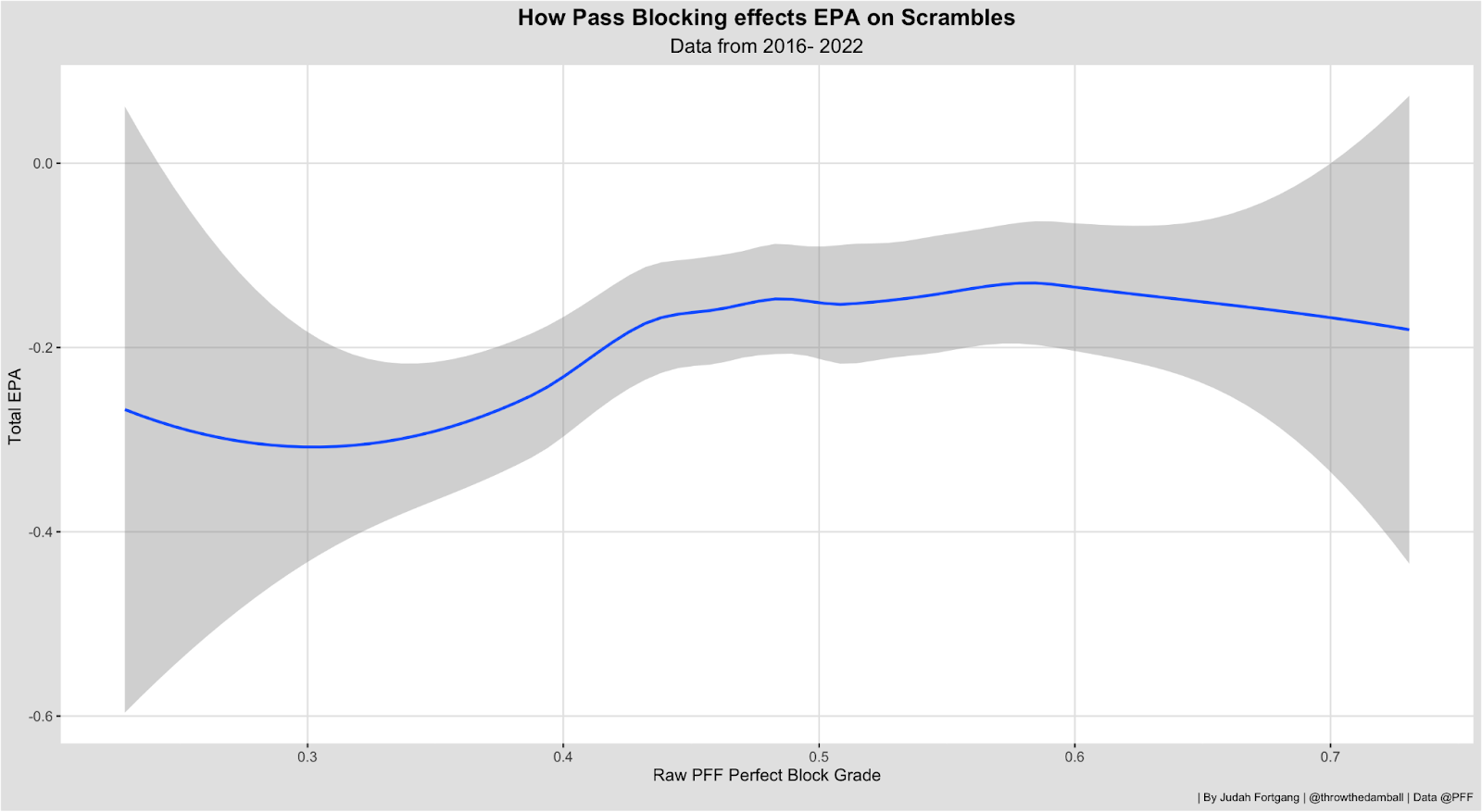

On offense, we can use perfectly blocked plays to judge the quality of play on a team level for an offensive line.

What this curve suggests is that up until the 40% point of perfect blocking rate — the average rate on scrambles is close to 50% — the offensive line seems to increase an offense's production. But after that point, the returns of having a good offensive line seem to diminish. Essentially, this suggests that barring a truly disastrous offensive line, the effectiveness of a quarterback when scrambling is mostly agnostic to offensive line play.

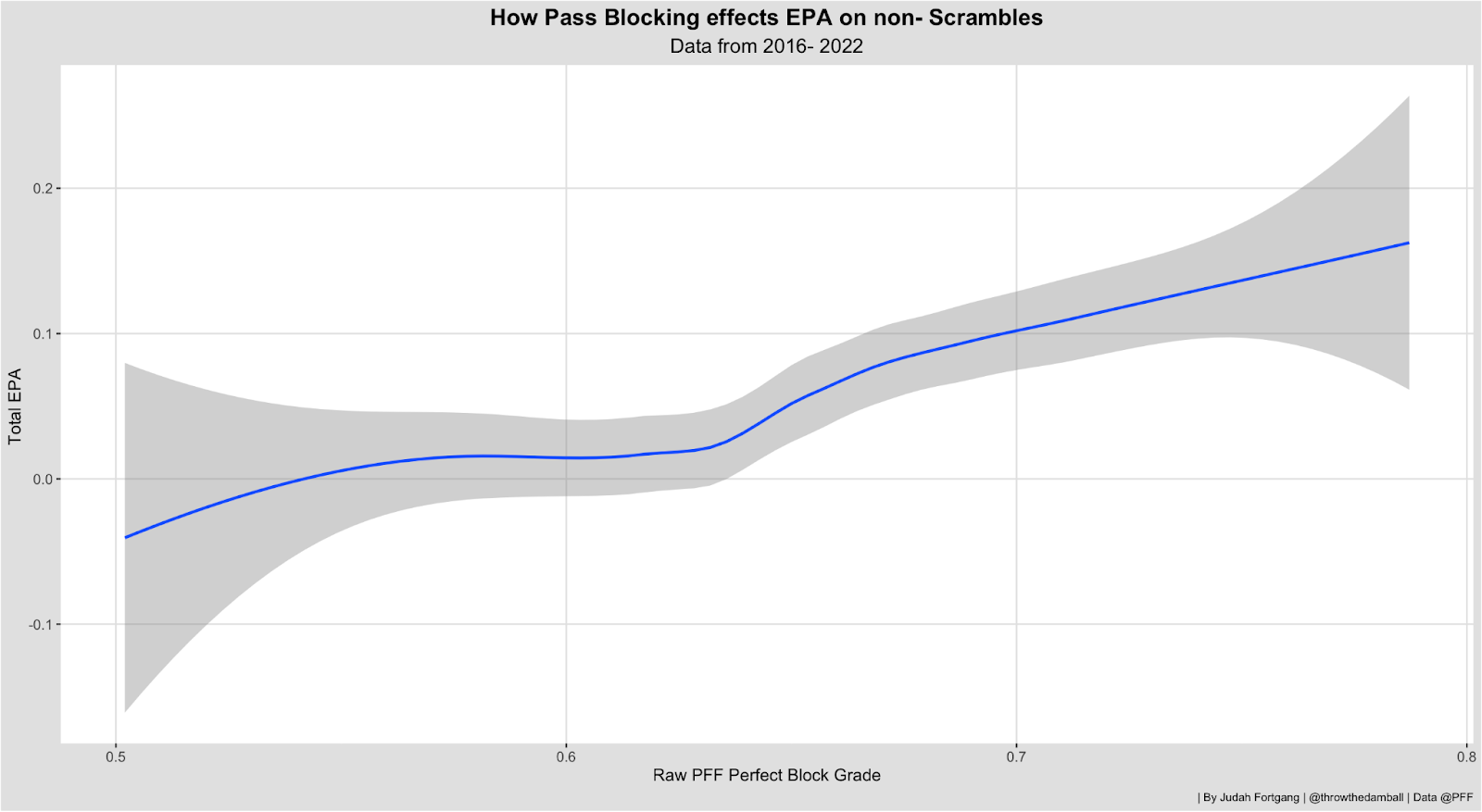

Meanwhile, on non-scrambles, the offensive line has much more of an influence on the success of a given play. The average perfect block rate is 65%, right around the point on the curve by which increased line quality greatly increases offensive production. With an above-average offensive line, a quarterback will begin to see significant increases in production as the quality of the line improves.

When not scrambling, a quarterback is more influenced by their surroundings. The signal-caller's upside can be capped due to poor offensive line production, or vice versa. When we discuss pocket passers, we will see how certain quarterbacks can help elevate their offensive line. But in general, quarterbacks are more sensitive to offensive line play when not scrambling.

Sticking to the offensive side of the ball, let's look at how receiving play interacts with quarterback production.

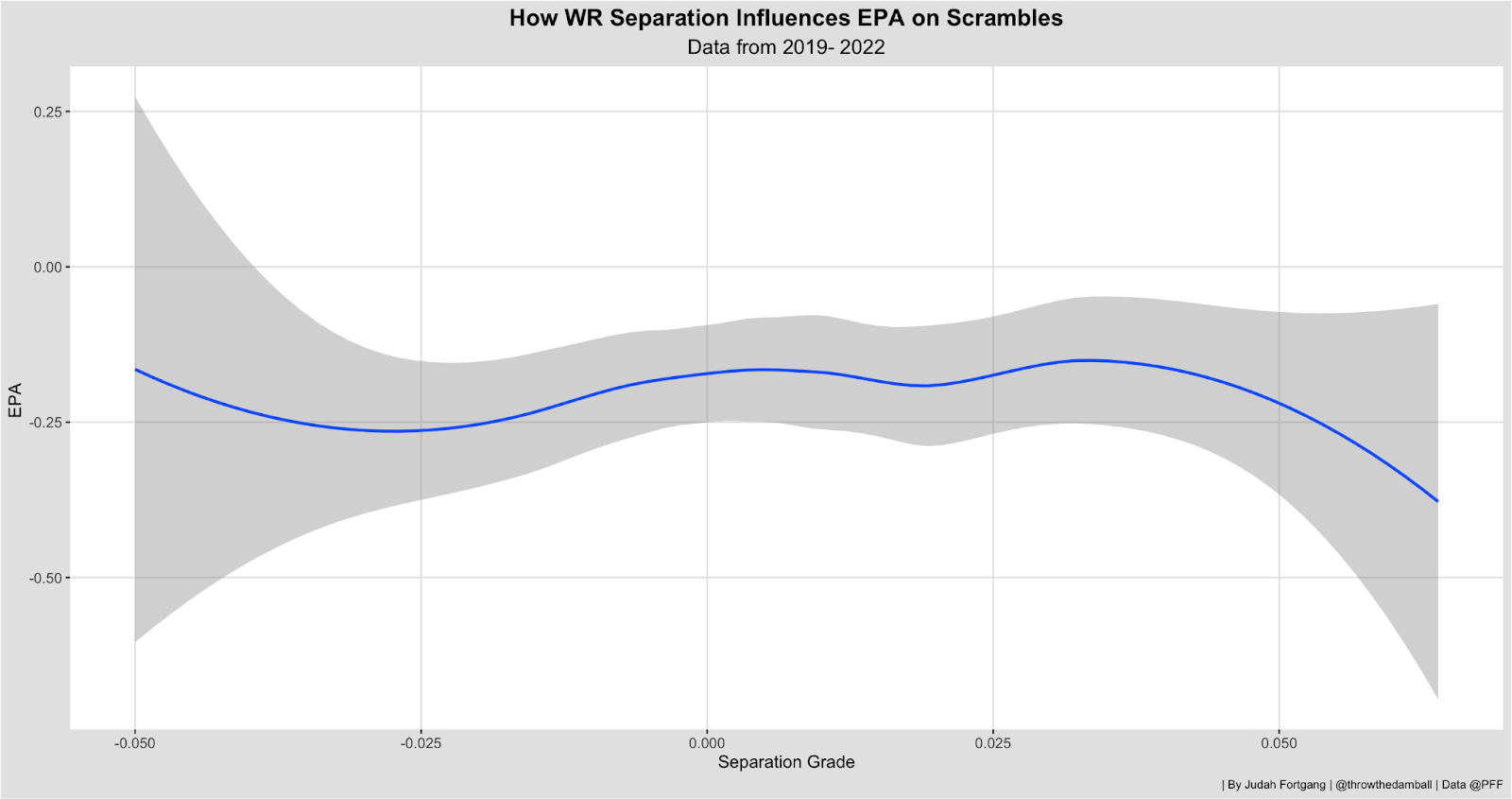

Better receiver separation (X-axis) does not correspond with increased production. This curve is similarly noisy if we filter our true scrambles to only include pass plays. There is certainly some selection bias at play — if a receiver has already created separation, there would likely be no need to scramble. But perhaps equally responsible is that the process of scrambling buys time through which receivers are open by virtue of the playing taking a long time. The receiver would be deemed “open” despite not generating a positive separation grade.

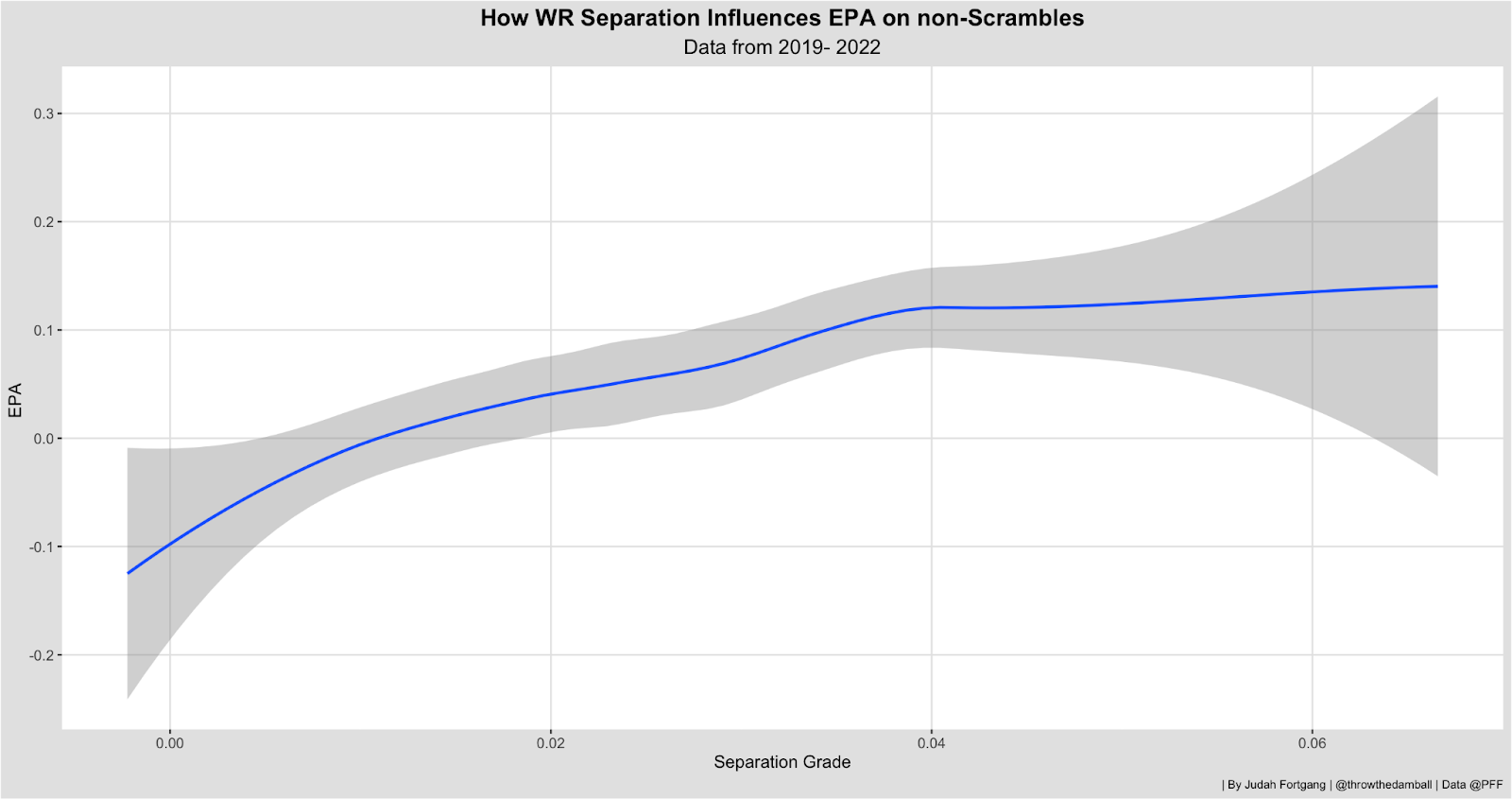

If we look at receiver separation on non-scrambles, an increase in separation ability corresponds with an increase in production, with production only beginning to flatten at about the 90th percentile rate of separation. The reason for this curve flattening is an interesting point for a different article, but this curve suggests that a non-scrambling quarterback with poor separators will likely be unsuccessful and that a non-scrambling quarterback with great separators has a far higher chance of success.

A larger theme should be emerging: Scrambling quarterbacks are much more situation-agnostic compared to non-scrambling quarterbacks. In general, how well their offensive line plays or how effectively their receivers separate doesn’t seem to have much influence on the success of a scrambling quarterback.

Of course, studying these interactions is not just academic in nature but has some important insight for fantasy football players, bettors and curious fans attempting to predict an upcoming NFL game or season.

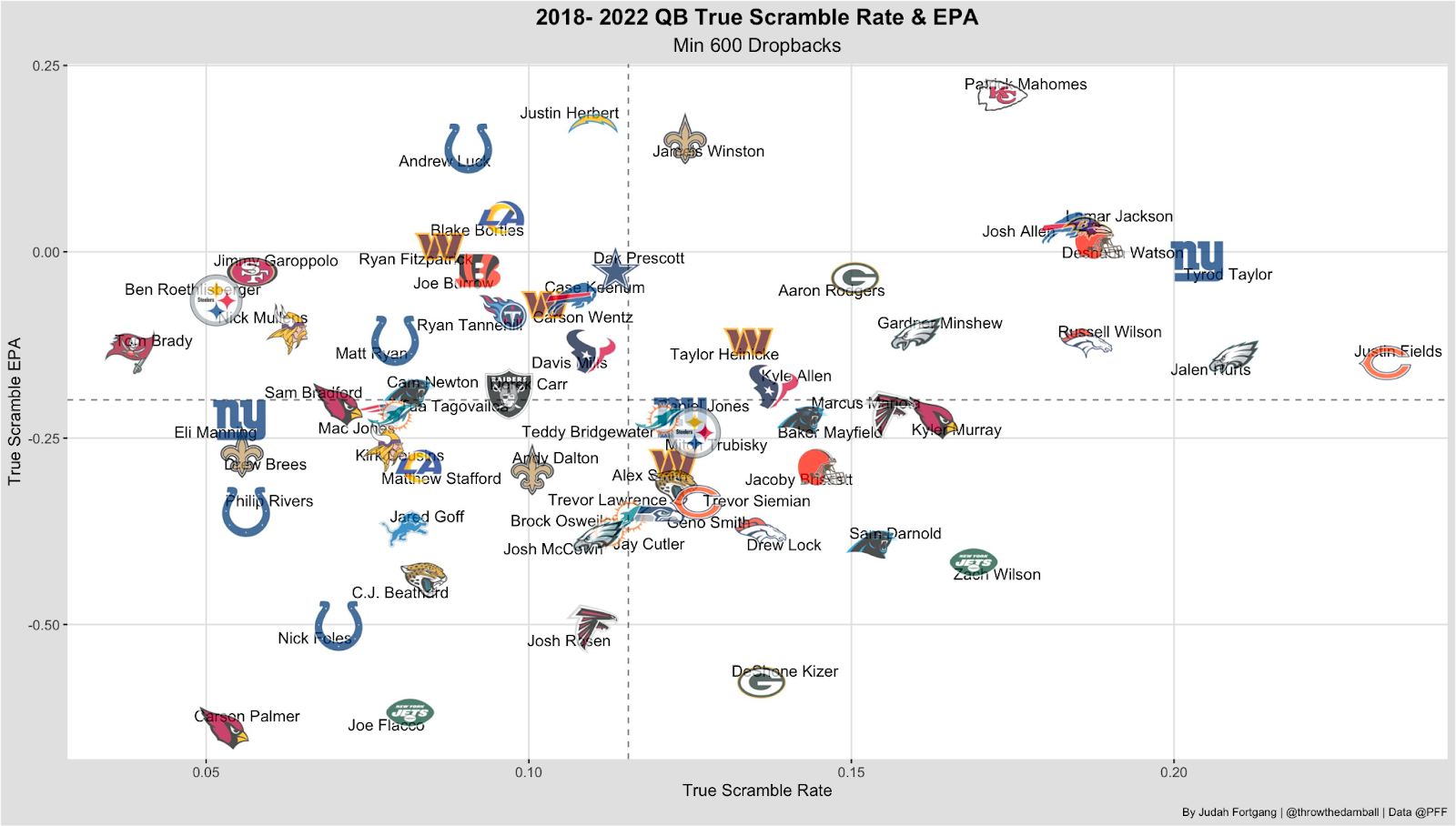

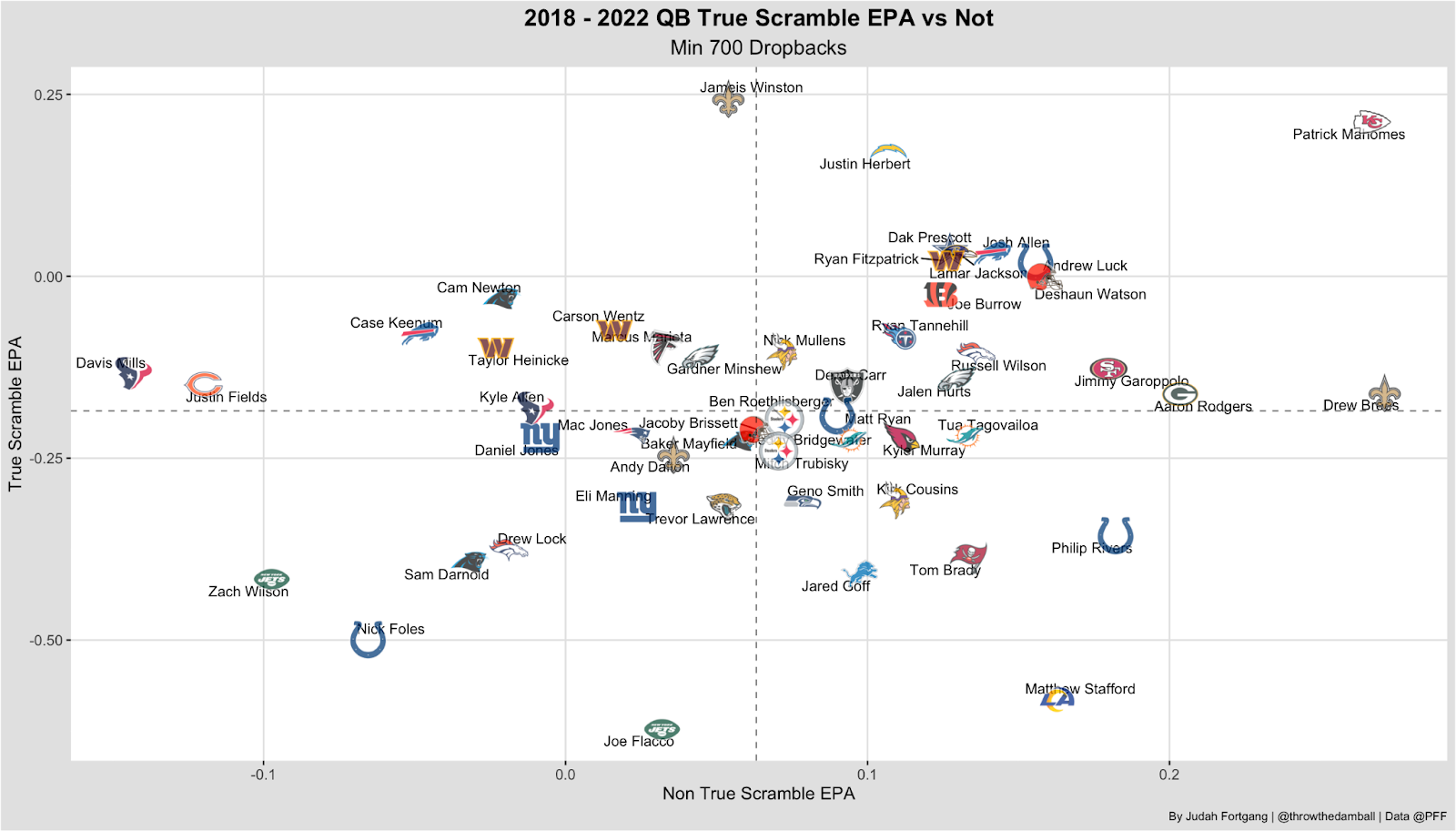

Players at the top of this chart — especially the top right — are far less sensitive to their situation. And those at the bottom left are much more sensitive. Something such as a few linemen going down in a given week or a receiver getting traded in the offseason would matter much more to Jared Goff or Mathew Stafford than to Patrick Mahomes, Aaron Rodgers or Lamar Jackson. The X-axis of this chart should also begin to give you a sense of some of the rates of quarterbacks who scramble often and their efficiency when doing so.

This should not be confused with a quarterback efficiency chart, as scrambling is only one skill among many. Sure, a good scrambling quarterback can help hide a team's weakness or elevate a team’s play against a tough defense. But scrambling isn’t a cheat code. If a quarterback is a poor decision-maker, isn’t accurate or struggles with some other trait, effective scrambling won’t solve all of their problems.

Here, we have a quarterback's production broken up into scrambling plays versus non-scrambling plays. Based on our research, the quarterbacks higher on the Y-axis are less situation-dependent, and those on the right of the X-axis have produced the best when surrounding talent and situation matter more.

Conclusion

While there is still more research to be done on this subject and throughout this series, this article suggests that true scrambling production is a stable skill that can better predict performance under pressure — where quarterback talent, devoid of structure and scheme, particularly shines through.

For this reason, scrambling has some of the widest distributions in play style and production. Effective and frequent scramblers tend to be much less prone to situational variance and have more opportunities to succeed. But while scrambling can cover up roster deficiencies, it remains only one piece of the puzzle that is quarterback play. We will continue this exploration in future articles in this quarterback traits series and update these numbers throughout the NFL season.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.