Just as the football play starts with a snap, so do all football practices. Whether it’s the center snapping to the quarterback or the long snapper sending footballs to his fellow special teamers, the holder and punter, the significance of a clean snap is not lost on football coaches and players. It’s hard to play this sport with any level of competency if the snap can’t be made routinely. A wayward snap will kill a play before it starts. A bobbled catch will do the same. You don’t want to hear the words, “Whoa, he has problems with the snap!” because it does not end well.

[Editor’s note: Subscribe to PFF ELITE today to gain access to PFF’s Premium Stats and new Player Grades experience in addition to the 2020 NFL Draft Guide, 2020 Fantasy Rookie Scouting Report, PFF Greenline, all of PFF’s premium article content and more.]

And yet, the course of football history might have been changed because of a bobbled snap. When Rich Rodriguez was coaching Glenville State in 1991, a zone running play in practice became the first iteration of the “zone read” when his quarterback bobbled the snap, saw the unblocked defensive end crashing inside and took it upon himself to run where the defensive end used to be. They say the mother of invention is necessity — but in this case, it was butterfingers.

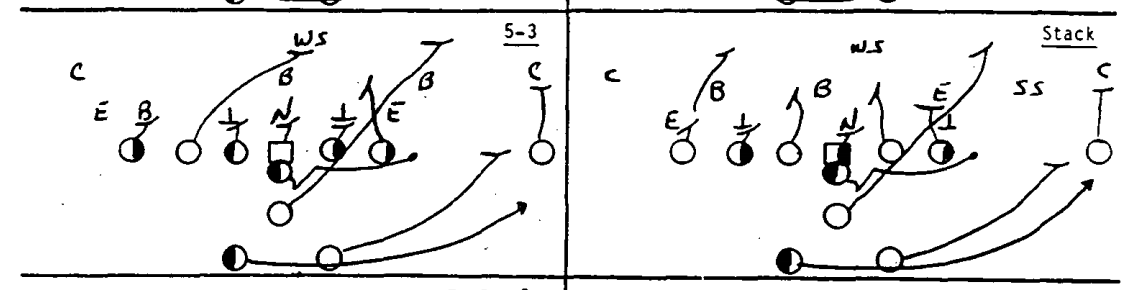

Zone running plays have always had the same problem. If all the offensive linemen are blocking in the same direction to the front side, how can the team deal with the player(s) who aren't blocked on the back side? Teams would often just let that player run free and pray he wouldn’t make the tackle. A naked bootleg by the quarterback could deter that player's run-and-chase behavior, but if he smelled something fishy, he could stop and play the unprotected quarterback.

The option offenses up to that point in football’s history had provided an answer to this problem. These teams would make that backside player a frontside player and read him.

The fullback slams down into the line of scrimmage, and the defensive end (or “End Man on the Line,” in football terms) must decide whether to crash down and tackle that player or wait and tackle the quarterback if they keep the ball.

One reason why that under-center option play became extinct was that as the Air Coryell and West Coast-ification of football spread to the lower levels, the skillset of the quarterback needed to change. The ball-handling and running ability of the quarterback became somewhat of an afterthought. Offensive football needed the pocket passer. This was going on while the proliferation of the shotgun formation was slowly becoming mainstream. It was thought that being in the shotgun hindered the team's running game, so it became mostly a passing formation.

At that point, the option was being slowly phased away from the game, and the only way an offense could run the ball with any diversity was from under center. Glenville State quarterback Jed Drenning’s now-famous bobbled snap helped bring the two together. Not only has the zone read stuck around almost 30 years later, but it has also proliferated all levels of football and become a Day 1 install for so many teams.

The name “zone read” is a two-parter. The first word is the running play and can be interchanged for almost any running scheme — in this case, it's “zone.” You can have “buck reads,” “counter reads,” “power reads,” you name it. “Read” is telling us that a defensive player is being left unblocked for the quarterback to option off of. That’s why the term “read option” is not technically correct. A read is an option.

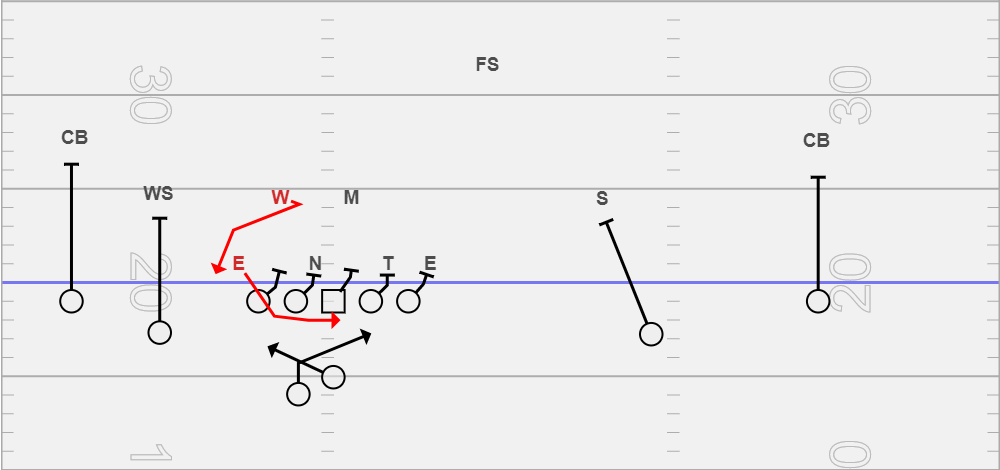

Zone Read

Counter Read

After stumbling upon this shotgun read stuff in 1991, it still wasn’t the base part of Rodriguez’s offense for a number of years. It seems like Rodriguez stayed true to his Run n’ Shoot roots but added some interesting quarterback run designs, such as a before-its-time “Stick-Draw RPO” seen in 1998 while he was the offensive coordinator for Tulane. You still see aspects of the zone read — but not as true base play. Of course, there is limited film of the great 1998 Tulane Green Wave team.

Later, as offensive coordinator at Clemson, we see more read aspects to Rodriguez's run game. This may be because Woody Dantzler was not the passer that Shaun King was at Tulane, so Rodriguez played more to his strengths. In fact, we see some “power read:”

(Whether that defensive end is being read is a question without an answer.)

When Rodriguez became head coach at West Virginia in 2001, we saw him slowly start to make it a more integral part of the offense. By that point, with Rodriguez having coached Tulane to an undefeated season and then been part of a successful campaign at Clemson in 2000, the radical idea of running option concepts while in the shotgun started to disperse itself throughout the football landscape. A young football coach who won’t be named (Hint: It’s me) used the zone/veer read in Urban Meyer’s 2002 Utah Playbook to absolutely zero success in 2008.

It was already becoming a staple in the coaching world, but the cultural explosion happened in 2005 when Pat White became Rich Rodriguez's starting quarterback midway through that season. West Virginia was already very good up to that point, as White split time with starting quarterback Adam Bednarik. The Mountaineers were 5-1 and averaging 24 points per game but found themselves down 24-7 against Louisville. An injury to Bednarik put White in the game, and he proceeded to lead West Virginia to a 46-44 win. West Virginia didn't lose again with White as the starter that season, with their points per game average rocketing to 40, including the Louisville comeback.

Against a Georgia defense in the Sugar Bowl that had allowed only two opponents to score over 20 points in a game that season, West Virginia scored 38.

The zone read found its way to the masses. We have NFL zone-read data only for the 2006 season and then from 2014-19, but the contrast is stark. In 2006, there were 75 rush attempts that we would classify as zone read. In 2014, there were 1,009. Once a scheme finds its way to the NFL, you know it’s big-time.

The zone read allowed teams to continue their modern fixation of being in the shotgun while also not forcing them to slot in bad quarterbacks to lead their offenses. We just assumed that if we taught footwork timing to a quarterback, they’d all become Joe Montana. We ended up with one Peyton Manning and 1,000 Ryan Leafs.

The option coming back into football full time has allowed so many more deserving players to become quarterbacks at an early age and, ultimately, play the position at a high level. Having a player who can even out the numbers advantage that the defense had played with for so long is important.

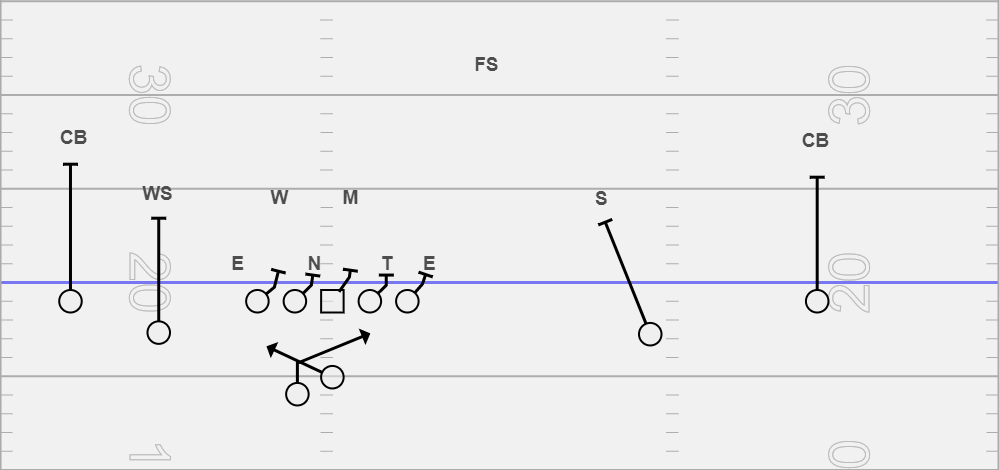

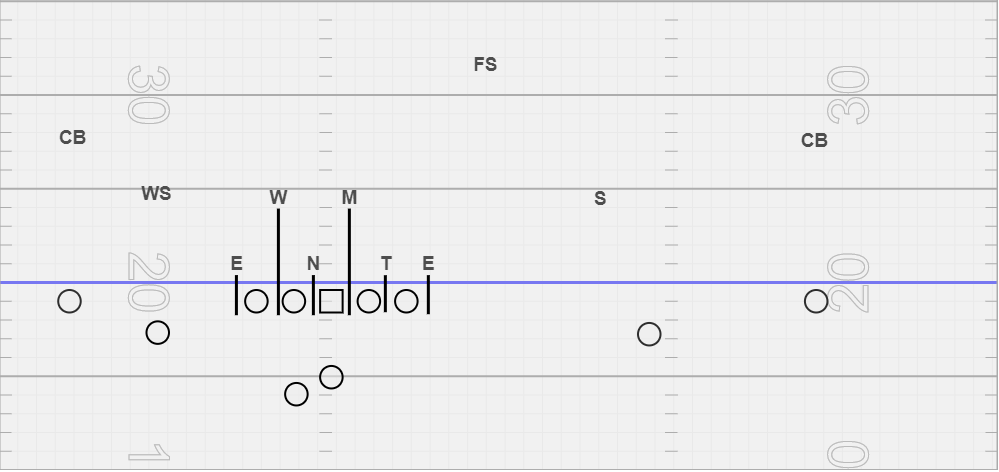

In a “4 Open” spread formation, the defense has to contend with six offensive gaps on a running play. If they chose to spin down one of their safeties into the box, they can allocate one defender for each gap:

One Safety Spun Down

Allowing the quarterback to be a potential running threat means the offense now has a pseudo seventh gap while the defense still has only six players in the box. All the math that defenses had relied on when teams would run their basic shotgun run plays was then out the window.

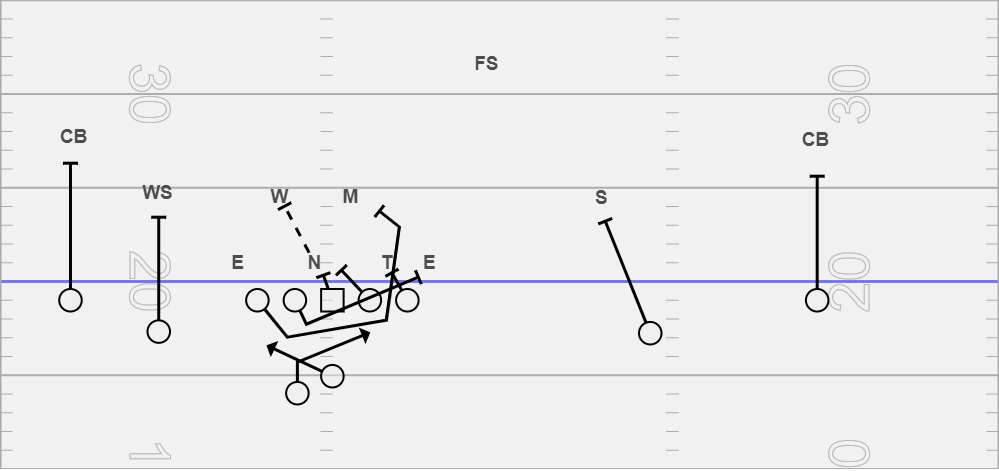

One of the first ways defenses tried to take back the numbers was to play a “scrape-exchange” technique. The scrape part has the defensive end chasing down the running back whether or not he had the ball. The exchange part tells the linebacker sitting on top of that defensive end that he now can sit back and wait for the quarterback:

Scrape-Exchange Technique

This puts the offensive tackle in a bad spot. He’s supposed to block the defensive player who is filling the B-gap. In a perfect world, that player is the linebacker shuffling over to stay in the gap. With the scrape-exchange, the B-gap defender is the defensive end who is now behind the offensive tackle. That's a tough block for a human being.

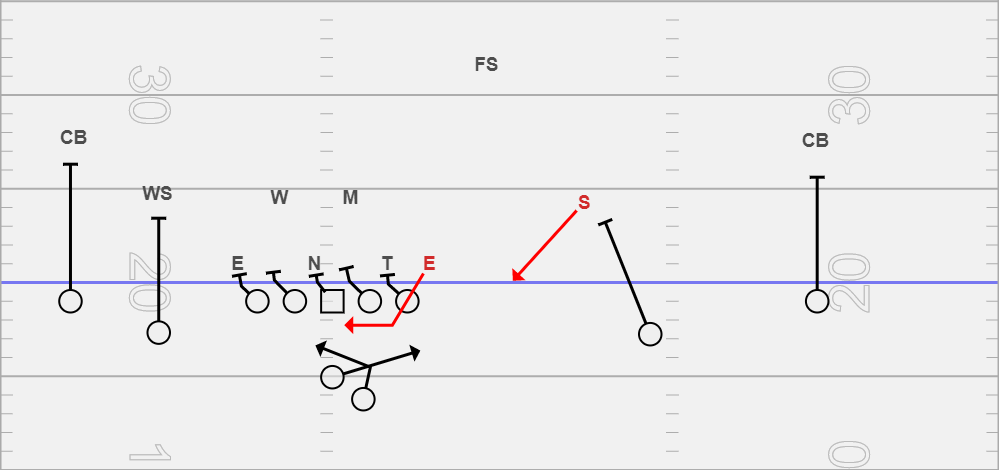

Offenses responded by having the offensive tackle step down, making it look like a regular zone play, before veering back and blocking either the defensive end or the linebacker. If they wanted the quarterback to keep the ball, they would leave the end and work back for the linebacker. If they wanted the running back to carry the rock, they would turn back for the defensive end and have the linebacker float to nowhere:

Another way the offense responded was by having Michael Vick:

Besides fancy combinations between box players, the other way to get the numbers advantage back was to trigger one of the “overhang” players into the box. If the zone blocking went to the weak side and the quarterback tried to slip out with the ball to the strong side, the Sam linebacker/nickelback could trigger and play the quarterback.

Overhang

I believe this is where the zone read went from “gimmick” to “mainstay.” It started having answers to everything the defense could do. It kept evolving. If an overhang defender triggered, you could pitch the ball out to the player that defender was supposed to be covering. The somewhat dormant triple option sprang to life again.

The possibilities are endless. First, it’s a pitch. Then, it’s a quick bubble throw:

Then, why not just throw it down the field?

The triple option makes you account for everyone on offense. Besides the outside pitch or throw phase of the play, other old option concepts have been reinvented for today’s game. The super spread “4 Open” era has given way to the era of three receivers, one running back and one fullback/tight end hybrid. Teams have started to use that bigger player like flexbone teams have used the playside wingback for decades.

Arc and Load blocks have come back in style. If the quarterback keeps the ball on the option, he has a lead blocker. It's another way to defeat the scrape-exchange.

You can bring this player all the way from the backside, which can create some confusion for the defense if the linebackers don’t bump over or the safeties don't rotate.

You can even throw your fullback/tight end a bone once in a while.

More and more option concepts started to be recycled from under center plays to shotgun plays. Chip Kelly’s Oregon Ducks made reading interior defensive linemen famous.

The advent of the pistol formation and the way Urban Meyer’s teams would run their veer read really solidified the idea that offenses could run true option concepts even if the quarterback wasn’t under center. The zone read chose a player on the backside of the run to read, but the pistol and veer read teams could go back to finding a frontside player to read.

Though the inside zone read has become the most common scheme to run in the shotgun read family, an offense can conceivably attach all sorts of running schemes to a read. The 2000s West Virginia squads heavily used outside zone reads. In today's age, late 2010s Oklahoma uses its ubiquitous GT counter scheme with a read on the backside. Run 379 times over the past four seasons, the GT counter read generated .270 expected points added (EPA) per play. Elite status.

The Baltimore Ravens ran a duo read to almost unlimited success in 2019. They ran it 163 times at .119 EPA per play.

The zone read and all of its brothers and sisters have stood the test of time because of its adaptability. From its accidental origins, the zone read was always more than just a play or scheme. It was an idea. It took a tried and tested football theory, the option, and paired it with the new shotgun offenses of the day. Old and new. Yin and yang.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.