I-Right, Check 34 Y-Pop. That was the first play I can remember learning as a kid, about 20 years ago. I remember it because it was a money play. And most importantly, it was my play. The second I heard “Check 34,” I knew a big play was coming.

If I saw that at a youth game today, I would heckle the coach for thinking he was Chuck Noll. The game today is much less static than it was at the turn of the 21st century, let alone decades ago. In the days of two backs and one tight end, everyone knew where the ball was going, and it was just a matter of whether a defense could stop it. Control the game, call your one or two big shots and cross your fingers.

Subscribe to

A head coach pounding the table about the team “doing what [they] do” wasn’t just a tired cliche but an accurate representation of the way things used to be. That’s not to say the NFL is any less homogenous today than it was a generation ago: only seven teams played 11 personnel on less than half of their snaps in 2020, and five of those seven are connected to the same West Coast offense coaching tree (Shanahan/Gruden). But, body types have changed, rules have changed, schemes and approaches have changed and the way we analyze the game has to change in kind.

Some data is more sustainable over the years than others, but few things in football are predictive of outcome from game to game. Over the stretch of a season, though, the best offenses generate the highest volume of explosive plays (15-plus yards). Only eight of the 38 playoff spots since 2018 have been taken by teams that fell below the season average, which typically holds steady around 110 total explosive plays. Of those eight, just one team below the threshold made the conference title game — the Green Bay Packers in 2019.

Now more than ever, there’s a better understanding and embracing of the fact that football is won almost entirely along the margins. That’s not new, but the margins to measure have changed. Yards per carry had a certain gravity in an era of running backs regularly carrying heavy workloads, but those days are long gone. 2011 was the last season with five running backs with over 300 carries, and we haven’t seen a season with 10 running backs notch 300-plus carries in 15 years.

In the past five years, the interception rate has dropped within a percentage point of the fumble rate on run plays: 2.3% to 1.5%, respectively. In 2020, only three teams had an average depth of target (aDOT) lower than seven yards, and 10 teams had an aDOT of nine yards or more. The old Woody Hayes quote about the probability of bad passing outcomes versus good is null and void today. Throw to score, run to win; this is the way of the game.

What does that say about the sport? It’s not really about controlling the ball and clock (turnover luck remaining equal) until time becomes a pressing restraint in end-of-half/game situations of one-possession contests. It’s not really about remaining balanced when there’s a 70-30 pass-to-run ratio in 11 personnel. Poor clock management and tendency imbalances can affect games (again, football is all about the margins), but these are smaller situational considerations that come down to game management.

What more reliably decides games is the team that can generate chunk plays and score touchdowns quickly. Since 2016, drives without any gains of 10-plus yards are 10% less likely to yield a touchdown. To find the offenses that generate the most big plays is to find the ones with the highest ceilings, and each offense has its own flavor.

Kansas City Chiefs

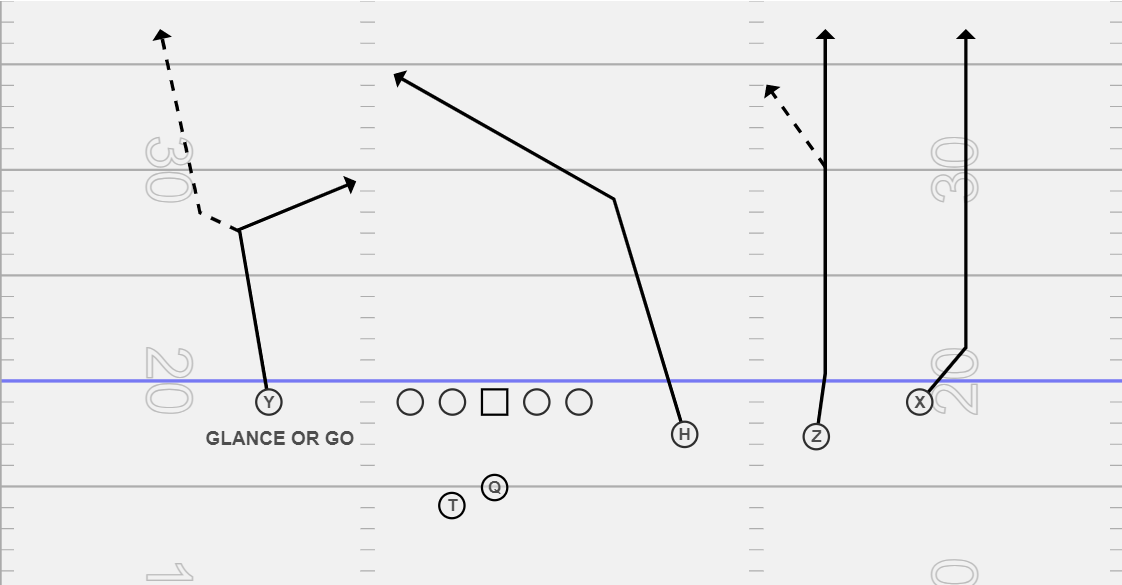

Money Play: Vertical Passes Out of Trips, Travis Kelce Split Out at WR

Rarely do you see offenses with two true No. 1 options as receivers. It’s doubly unlikely that they have the versatile skill sets of Travis Kelce and Tyreek Hill. When Kansas City gets into trips formations where Kelce is isolated and Hill is the No. 3 wide receiver, defenses are in a bind. If defenses prioritize protecting the middle of the field at the expense of more one-on-one matchups underneath, the two superstars will expose them.

Los Angeles Rams

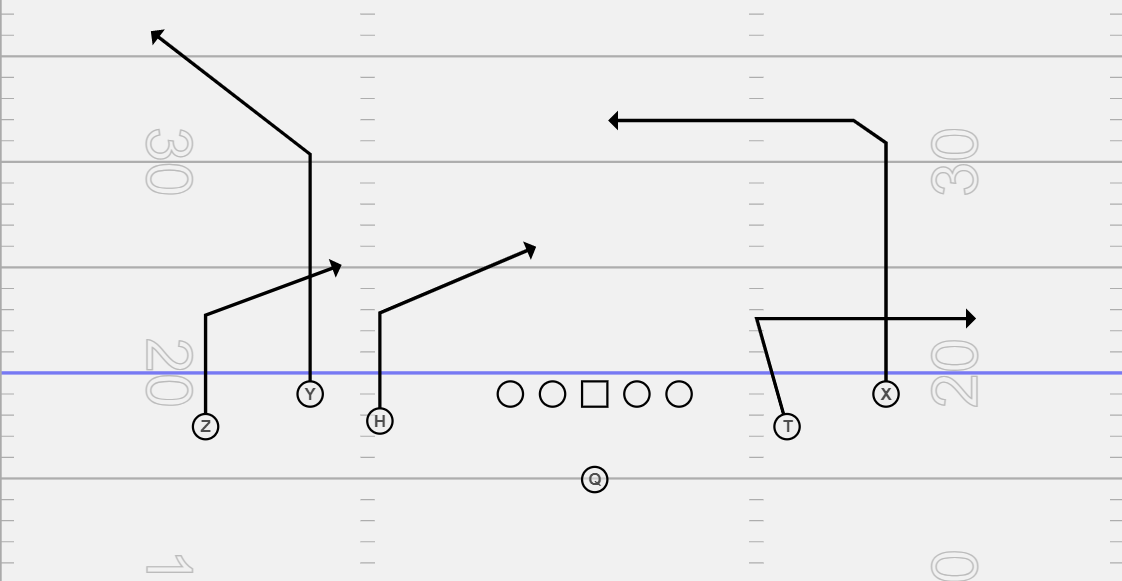

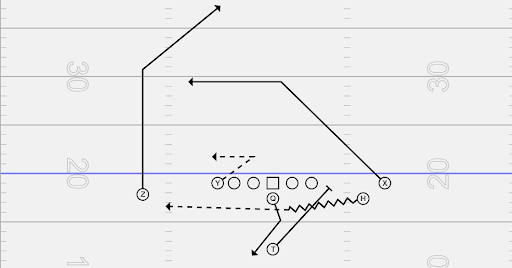

Money Play: Double Smash + Backside Dig Out of Empty

Unlike the once-in-a-generation talent collection in Kansas City, offenses typically need to manufacture space for vertical throws or after-the-catch opportunities. The best concepts allow a quarterback to get the ball where it needs to go against blitzes, man and zone coverage. Jared Goff has been asked to operate out of empty his entire career, and his 394 empty dropbacks since 2018 is second only to Deshaun Watson.

Head coach Sean McVay hasn’t strayed from his bread and butter, though. The jet motion that sets up outside zone and play action is still a hallmark of what the Rams want to do on offense, and 2×2 formations in 11 personnel generated just as many explosive plays (31) as Los Angeles had out of empty.

Buffalo Bills

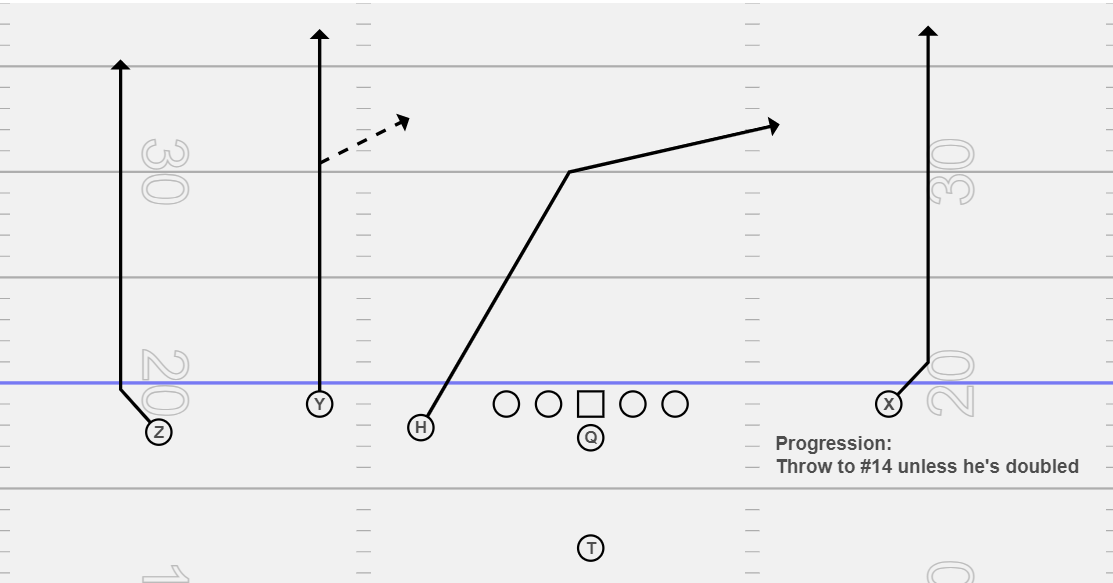

Money Play: Vertical Shots via Play Action

The Bills' offensive approach and roster moves meshed perfectly with a breakout season from quarterback Josh Allen. Wide receiver Stefon Diggs made an immediate impact and logged a career-best 90.2 PFF grade. In spite of the issues in the run game, Buffalo was able to generate high returns on investment from play action and max protection, ensuring that Allen had the time he needed to push the ball downfield in spite of inviting more pressure than most.

Bills Passing Offense in Play Action and 7-Man Protections

| Passing Series | Snaps (Rank) | Passing Grade (Rank) | Passer Rating (Rank) | EPA/Play (Rank) | Average Depth of Target (Rank) | Pressure Rate (Rank) |

| Play Action | 226 (1st) | 91.4 (3rd) | 116.0 (7th) | .313 (6th) | 11.4 (4th) | 27% (26th) |

| 7-Man Protection Passes | 43 (18th) | 89.4 (6th) | 113.2 (9th) | .403 (8th) | 14.4 (11th) | 23.3% (7th) |

New Orleans Saints

Money Play: Stealing Whatever Sean McVay Did in 2018?

Considering Drew Brees‘ average depth of target was below seven yards over the past two seasons, then-offensive coordinator Joe Lombardi and head coach Sean Payton may have been the best in the NFL at manufacturing explosive plays. Despite Lombardi and Payton having no real connection to the McVay or the Shanahan coaching tree, you’ll see plenty of the condensed splits, outside zone and play-action shots that are central to “Shanny-ball.”

Cleveland Browns

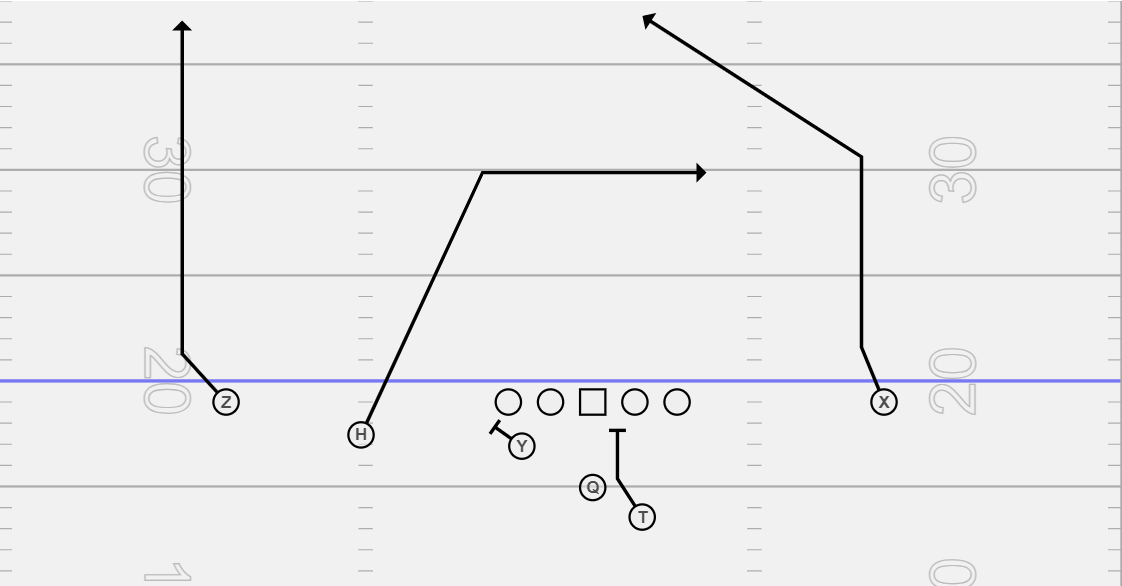

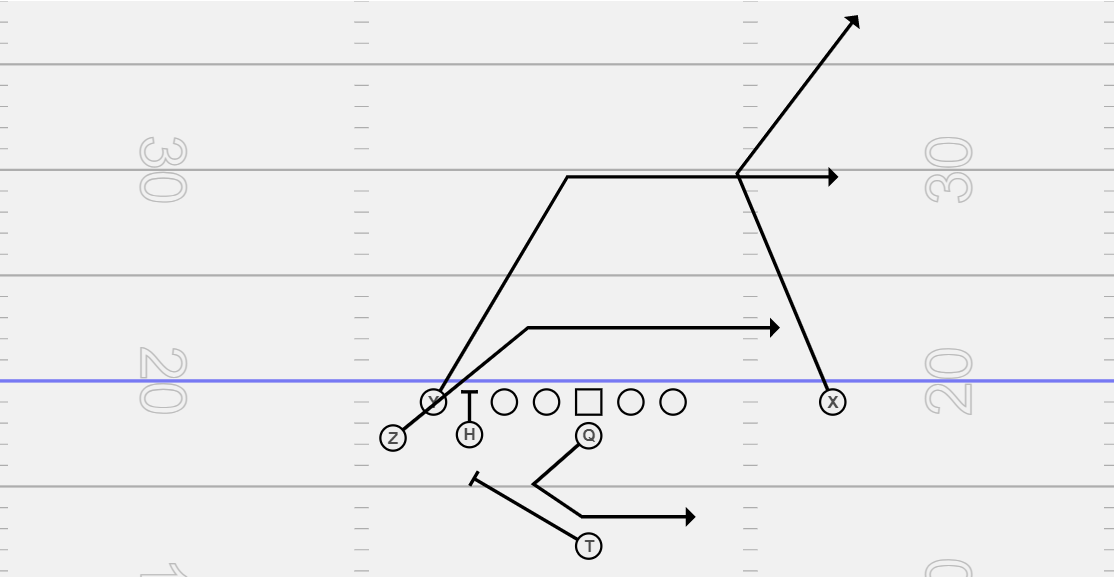

Money Play: Sail Concepts via Play Action

We’re reaching the point of trend recognition: aside from New Orleans, the teams that are best at generating explosive plays are all off of the same coaching trees. Even the Saints are running an approximation of what Andy Reid and Shanahan have popularized in the NFL.

| Play Series | Grade (Rank) | EPA/Play (Rank) | Explosive Plays (Rank) |

| Outside Zone | 80.5 (4th) | .042 (3rd) | 22 (2nd) |

| Play Action | 90.2 (6th) | .260 (11th) | 40 (T-6th) |

Kevin Stefanski’s take on the Shanahan scheme has returned instant results for the Browns. The potency of the outside zone run in this offense helps to set up the bootleg plays that often find wide receivers crossing the field with no one close in coverage. It seems like the backfield pairing of Nick Chubb and Kareem Hunt was built for this, and Baker Mayfield reaps the benefits in the pass game.

Because of the condensed splits with the threat of perimeter run, defenses have to play soft in coverage and with more eyes in the backfield, and by the time a safety or linebacker realizes what’s happening, the receiver is already 16 yards down the field.

Seattle Seahawks

Money Play: Absolutely Abusing Defenses With D.K. Metcalf

I’m unsure of what data best illuminates the point that D.K. Metcalf cannot be guarded in single coverage. In his 280 snaps against Cover 1 and Cover 3 last season, his 89.4 grade ranked 11th, and his 18 explosive plays tied for eighth in the NFL. He ranked in the top 10 in touchdowns and first-down receptions combined against single-high coverage, and his depth of target and yards per route run both slotted in the top 20 of receivers with at least 100 snaps. If a defensive coordinator sees Seattle in trips, they better have a coverage check in their back pocket.

Tampa Bay Buccaneers

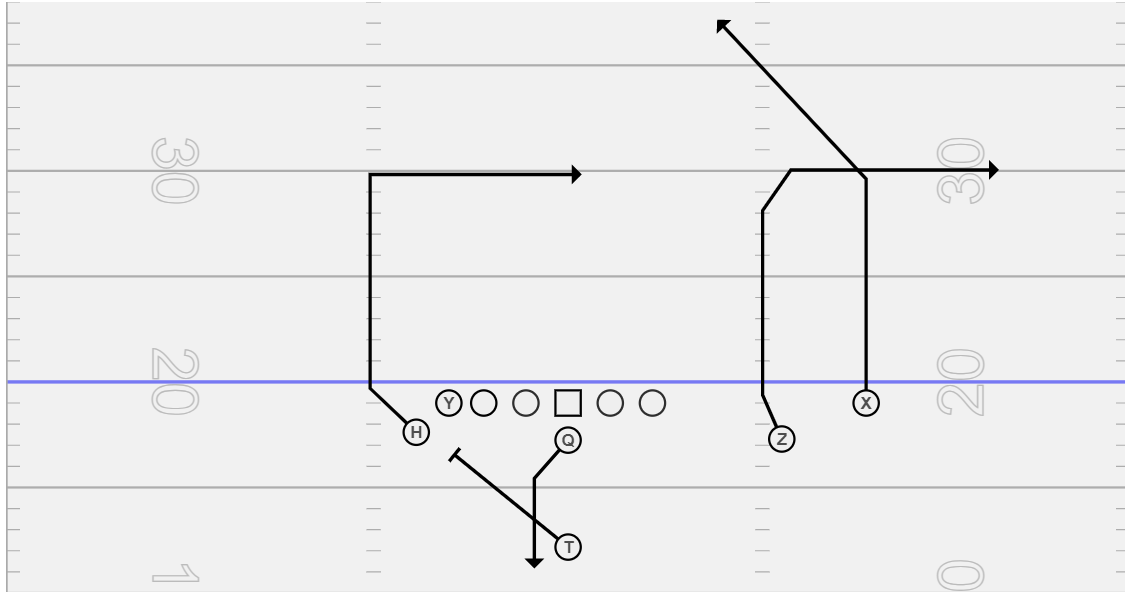

Money Play: Scissors Concept off of Play Action

The reigning Super Bowl champion is as good as any team at filling stat sheets with chunk plays. Only six other teams generated more explosive plays than Tampa Bay in 12 and 13 personnel last season, and just four did so more often with play action.

Just as the Shanahan tree uses outside zone to set up play action, the Bucs do with “duo,” a man blocking scheme. Using two- and three-tight end sets, Tampa Bay’s 75.7 grade on those runs ranks fourth, and their .222 expected points added (EPA) per play mark is second to only the Tennessee Titans in teams with more than 20 such snaps. The downhill action gives the defense something it has to honor, and the speed on the perimeter helped quarterback Tom Brady deliver a 93.4 grade on his 58 play-action dropbacks in 12 and 13 personnel.

This season, with the added 17th game on the schedule, the explosive play threshold will likely land around 115. The teams that can meet and exceed this mark will have the kind of scoring potential needed to vie for a playoff run. Any team below it would need to rely on its defense and lack of opponent strength to feel good about its chances.

The days of pop passes and two-man route combinations are about extinct. Almost every team covered in this used vertical passes to generational talents or came off play action to generate big plays. Offenses looking to raise their ceilings will need to manufacture space with bigger personnel or condensed sets, hard play action and deep crossing routes.

Baseball and basketball figured it out: everybody digs the long ball. It’s football's turn to join the parade. Every play isn’t designed to score or gain chunks of yards, of course. This is still a game won and lost along thin margins. In the end, though, the numbers that win games are the ones that go on the scoreboard, and the best way to that destination is getting downfield as often as, and by any means, possible.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.