When the Kansas City Chiefs got stopped on 3rd-and-14 with 1:45 to play in the first half, it seemed like the San Francisco 49ers had the chance of going for the double score that would have come about by scoring on the last drive in the second quarter and then, after getting the ball to start the second half, scoring again to potentially go up by 14 points before Patrick Mahomes even got the ball back.

However, Kyle Shanahan, who has proven to be an excellent coach over the last four years, chose to save all of his three timeouts and let the clock wind down to 59 seconds after the Chiefs' punt. This begs the question: What was his possible rationale?

Timeouts have hardly any value compared to time in a two-minute drill

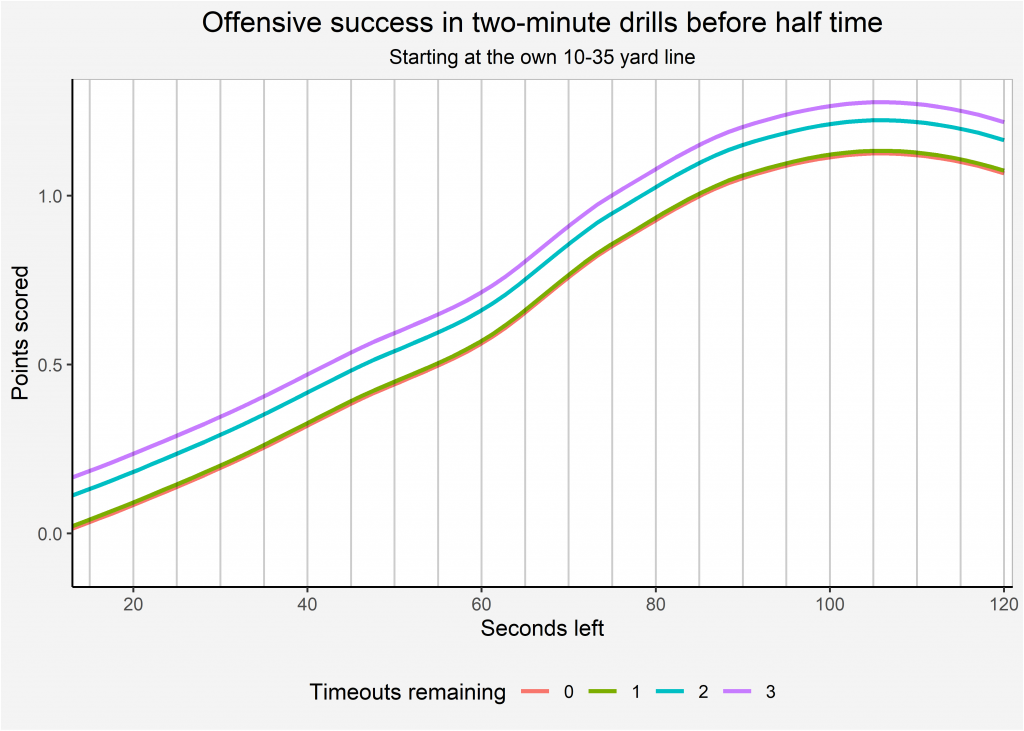

Did he possibly think, with the goal of scoring in mind, that the third timeout would be more helpful than the additional 40 seconds? That's really unlikely, as it is intuitively clear that two timeouts and 100 seconds is much better than three timeouts but only 60 seconds — that is, of course, if you actually want to score.

To support this with data, we've analyzed all two-minute drills late in the second quarter since 2006 (restricting to games that were still within 14 points so that the possessing team usually has the intention to score), and we found that saving timeouts is not necessarily a good strategy, as having more time on the clock is more crucial to scoring than having all three timeouts.

The curves suggest the third timeout yields diminishing returns compared to having two timeouts, most likely because it's not even a sure thing that you have the opportunity to call all of them. With 100 seconds and two timeouts remaining, teams averaged more than twice as many points than with 60 seconds and three timeouts left.

Separating the process from the results is crucial

On their first play of the drive in question, Shanahan called a run, which ended up going for 3 yards. He still refused to take a timeout, letting the clock run down to 26 seconds, essentially ending their scoring opportunity. This suggests that Shanahan didn't intend to maximize his opportunity of scoring before halftime, and he confirmed this right after the game.

Kyle Shanahan, speaking about the end of the first half strategy, said he felt “really good at 10-10.”

— Gregg Rosenthal (@greggrosenthal) February 3, 2020

This has us believe that Shanahan was scared to give the ball back to Patrick Mahomes. Given Mahomes' ability to score from any position, this might seem reasonable, but when you play an offense as strong as the Chiefs, the best chance to win is to score on as many drives as possible.

The thought we want to use to illustrate this is the following: When you are aggressive in this situation, you risk giving the opposing quarterback an opportunity to score before halftime in a game that is tied at 10. Andy Reid surely would have liked to score there, but it wouldn't have been a must-score situation, so you can expect Reid to also be somewhat conservative (Kevin Cole pointed out he has a history of doing this), for example, by not going for it on a potential fourth down.

But by being conservative, you increase the risk that the opposing quarterback will have an opportunity to win the game later in the fourth quarter on a drive where he is in a must-score situation, one in which he will try to score, by all means, using all four downs. This is exactly the situation Patrick Mahomes found himself in on two consecutive drives in the fourth quarter. The chances that the Chiefs score on these drives are higher than on a potential drive that starts just before halftime.

At the point of his decision, Shanahan only thought of the negatives around being aggressive and not how the same negative (with a potentially higher magnitude) can occur due to his conservativeness, and he certainly didn't think that it might ultimately cost him a Super Bowl title.

It's a natural question to ask why he might have thought this way, and we have to look no further than the regular-season game against the Seattle Seahawks in Week 10. The 49ers found themselves in a comparable situation in overtime: They got the ball back with 1:50 to play, and instead of playing for a tie, Shanahan played it aggressively and had Garoppolo try to pass for a first down. They couldn't execute, Russell Wilson got a last chance to win the game, and the Seahawks signal-caller did just that.

When assessing this decision, it is crucial to forget about the outcome and exclusively evaluate the process. In Week 10, there might have been some factors that turned it into a questionable process. For example, his best offensive weapons in George Kittle and Emmanuel Sanders weren't on the field. These factors didn't play a role yesterday, and while we can't read anyone's mind, we can imagine the negative outcome in Week 10 played a role in Shanahan's decision, so we would like to point at this as a perfect anecdote as to why one of the most crucial commandments of decision-making is to evaluate the process independent of the result.

After wasting roughly one minute of time, Jimmy Garoppolo and George Kittle nearly saved their head coach with a connection on a deep throw, a play that was subsequently called back for offensive pass interference, but even this wouldn't have changed the fact that Kyle Shanahan undoubtedly mismanaged the clock and consequently threw away an opportunity to put the Chiefs in an even deeper hole, a hole that even Patrick Mahomes might not have been able to climb out of.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.