Week 2 of the 2021 NFL season started with an unexpected competitive game between the New York Giants and Washington Football Team, ended with Aaron Rodgers reasserting his dominance within the Green Bay Packers‘ offense and showcased another memorable duel between Patrick Mahomes and Lamar Jackson.

Outside of the primetime games, here are four things I liked and disliked most from Sunday's action.

Click here for more PFF tools:

Rankings & Projections | WR/CB Matchup Chart | NFL & NCAA Betting Dashboards | NFL Player Props tool | NFL & NCAA Power Rankings

Liked: Tennessee Titans Crushing Another Defense in 12 Personnel

The way the Titans play on offense is somewhere between a teenager on Madden 22 and a football nerd's fever dream — spamming the same plays over and over again. If Tennessee could build the entire offense out of downhill runs and play-action passes in 12 personnel, it would. It’s been, by a significant margin, the most impactful personnel group for the Titans in the three seasons leading up to 2021.

Aside from running the ball in 2019, a look at the data says that just about any play call out of 12 personnel got Tennessee closer to putting points on the scoreboard.

| Titans 12 Personnel | Total Snaps | Pass Grade | Passing EPA/Play | Rushing Grade | Rushing EPA/Play |

| 2020 | 336 | 81.1 | .323 | 86.1 | .115 |

| 2019 | 272 | 91.7 | .269 | 75.4 | -.055 |

| 2018 | 271 | 85.8 | .474 | 68.8 | .023 |

I’ve written before about the “evolution” of the modern offense and using the second tight end in a role between the sixth offensive lineman and a quasi-full back, and no one embraced the latter as much as the Titans. Between 2018 and 2020, Tennessee used 12 personnel bodies to make 21 personnel formations more often than any team in the NFL (210 snaps, a near-50 snap lead on the next in line), and it fit the personnel.

Jonnu Smith could be used as a true inline tight end (92% of “two-back” 12 personnel formations), and players such as Luke Stocker and MyCole Pruitt were more valuable (if not exclusively valuable) as blockers — logging 84% of their combined snaps in the backfield in those “12 to make 21” personnel looks.

Smith's departure has changed the context of the offense’s 12 personnel package in 2021. It’s only a two-game sample size in 2021 — and thus subject to rapid change — but tight ends Geoff Swaim and MyCole Pruitt have yet to log a single snap in the backfield in a 12 personnel formation. That’s telling me that new offensive coordinator Todd Downing has to approach this package much differently than now-Falcons head coach Arthur Smith did when he had the reins, and that’s changing the profile of the run game.

| 12 Personnel Run Game | Top Run Concept | Second Concept | Third Concept |

| Titans 2018 – 2020 | Outside Zone – 39% | Inside Zone – 33% | Man (Duo) – 18% |

| Titans 2021 (2 games) | Outside Zone – 58% | Man (Duo) – 33% | None (1 QB Sneak) |

Eventually, a continued over-reliance on just two run schemes will invite defenses to bring blitzes off the edge to stop those calls. But against Seattle in Week 2, it was all that was needed.

What Tennessee is doing in 12 personnel to adjust to the loss of Smith is creating four-man surfaces — and sometimes five — by aligning both tight ends on the same side, stretching the edge of the formation as wide as it can get. Wide receivers A.J. Brown and Julio Jones are “short” motioned into the formation if there’s a player on the edge the tight ends can’t block, and that sets up the two run schemes.

The run support players are pushed so far away from the point of attack, and there’s so much lateral movement on outside zone plays, that even if a defensive lineman wins his matchup, there’s enough air space to cut the ball up vertically.

The counterpunch is “duo,” which gets as many double teams at the point of attack as possible and isolates the linebacker with the running back. As soon as that linebacker looks to fit his original gap, Derrick Henry is going to bounce to the edge and get a one-on-one matchup with a hopeless cornerback.

This sets up the situation quarterback Ryan Tannehill is most comfortable in: running play action with enough pass protection to allow him to push the ball downfield. The losses of Smith and Corey Davis hurt, but replacing them with a healthy Julio Jones is a sufficient salve. Tannehill averaged 16 yards per attempt on 12 personnel play actions in the first two weeks of the season, and both of his incompletions were drops.

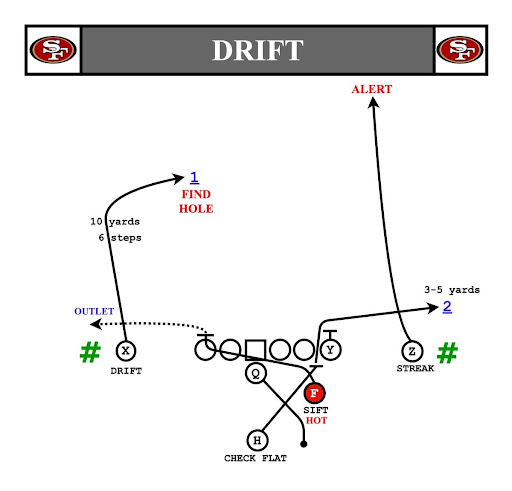

The “drift” route is the king of play-action passes out of heavier personnel. It almost acts as a “pop” pass, with the quarterback looking to fit the ball into a window between the second- and third-level defenders. In the clip below, A.J. Brown catches the ball and takes contact from the safety in the middle of the field right after.

This is an important piece of intel for an offense — it lets the quarterback know that the defense is much more concerned with the free safety being involved in cleaning up the run fit and coming down hard on intermediate routes than protecting his corners on vertical throws. The very next completion on the drift concept was over the top, hitting Julio Jones on the streak route.

As far as the lack of a two-back offense, Tennessee does have a full-time fullback in Khari Blassingame. However, Tommy Hudson — the fourth tight end in usage — has more snaps (18) than Blassingame. Again, this is about signaling, and that tells me the old 12 personnel package is out of the playbook. At least for Week 2, the pared-down package was enough to secure a win.

Dislike: Zach Wilson’s day against Bill Belichick

Wilson is the latest rookie quarterback to be put in the New England Patriots' blender. He finished with 19 completions on his 39 dropbacks, but his first two passes to be caught Sunday were by Patriots defensive backs. To be fair, only two throws were ultimately charted as turnover-worthy plays, but those were the third and fourth interceptions Wilson gave away on the day, and each one felt as though the decision-making got progressively worse.

Related content for you: NFL Week 3 best bets via Eric Eager and George Chahrouri

The first interception came on a “dagger” concept after a play fake. Both receivers are running in-breaking routes, and they are taught to sit in a window against zone and run through against man. When Wilson gets his feet set and his head around, he’s counting on his wide receivers to give him information on the coverage concept that he missed while his back was turned to the secondary.

With the first in-breaking route sitting down over the ball, Wilson tries to fit the ball in a tight window as though it’s zone coverage, and a batted ball turns into a pick. This is a classic rookie error, and as he develops, he will come to understand that receivers can get bad intel as they run their routes, and the best course of action is a throw into the third row.

Wilson is almost entirely absolved of the blame on the second interception in my eyes. This play-action look is a bootleg, with a “sail” concept designed to create three levels of routes: a deep corner, an intermediate crossing route and a slide route underneath in the flats.

Wilson’s process was on point here. The corner route takes longer to clear out than it should, but Wilson is staring right at the cornerback to confirm he’s dropping deep before firing the ball to Corey Davis on the over route.

Just like a rookie is apt to do, his concern that the window will close before his feet are ready leads him to throw while rolling right, and the ball will almost always tail high and away as a right-handed quarterback. Davis got hands on it, and while I’ll always shout “be a professional” at my TV in these instances, Wilson can make some minor tweaks to his feet to get the result he’s after.

Now, the third interception is a case of good defense being bolstered by a bad decision from the quarterback. This is a “snag” concept, trying to stretch the defense horizontally with a slant or drag from one receiver, a corner route from another and a third out in the flats.

The progression against zone is to wait for the corner and flat route to expand defenders into their zones, and then hit the slant/sit route. Against man, the quarterback checks to see if the player covering the flat route got picked/rubbed by the slant, or to take the corner route if there’s a matchup advantage.

Just like the first clip, there are times where the defense wins. The Patriots won Super Bowl 49 because of how skilled the defense was at handling man beaters, and this was another situation that Wilson should’ve submitted to the fact that the offense was beaten. The lack of velocity on the throw suggests a quarterback who yelled “Oh, no” as soon as he wound up.

By the fourth pick of the day, it was clear Wilson had lost the confidence he had before opening kickoff. Second-and-28 is already a major defensive advantage, and Belichick threw something at Wilson that he probably thought he’d seen the last of after leaving BYU: drop eight zone coverage.

The Jets try to “orbit” motion a wide receiver out on a swing route, and if he goes uncovered, there’s a major yards-after-catch opportunity to be found in dumping it off. To protect the corner from being conflicted in his Cover 2 flat drop, New England peels an end off to account for the motion man. It’s another “sail” concept, and the clear-out route should fade to the sideline so the intermediate route can settle in a hole, but the receivers don’t recognize until too late to adjust the route landmarks after all the man coverage New England had been running.

Wilson just heaves an arm punt right into Devin McCourty’s arms, clearly taking an ill-fated shot in the dark. Burn the tape and never mention this game again, Robert Saleh.

Dislike: Arizona Cardinals Fitting The Run

I joined PFF to create carefully considered takeaways from data and film study, such as the following: The Cardinals really stink at stopping the run.

The team's run defense is bad by every metric and on every level. Arizona surrendered 5.64 yards on average before making a tackle in Week 2, and that’s assuming that a tackle is made at all. The Cardinals' 10 missed tackles against the Minnesota Vikings, a mark that was outpaced by only the Houston Texans.

To finish the game with a 27.2 run-defense grade in spite of tallying six tackles for loss or no gain speaks to how poorly the unit performed — and the film shows that each of those tackles came on a run blitz of some kind. The only way the defense can find any success is by selling out to get it.

| Vikings Run Schemes | Run Snaps | Yards Per Carry | Runs of 10+ Yards | Missed Tackles Forced |

| Outside Zone | 13 | 5.2 | 5 | 5 |

| Inside Zone | 7 | 4.9 | 0 | 1 |

| Power | 2 | 6.5 | 1 | 3 |

| Pin & Pull Scheme | 2 | 9.0 | 1 | 1 |

I’m unsure of the rhyme or reason behind the rotation of the safety shell and who the run support players are, and the Cardinals are routinely caught with nobody to fit extra gaps created in the run game. The jet motion on this zone play is tied with a “split” action, meaning the tight end is cutting back across the field to kick out the backside end.

Because nickel corner Byron Murphy Jr. is traveling with the motion, the defense is sound against the threat of the jet sweep, and linebackers should be playing the zone run honestly.

However, the split action truly cuts the defense down the middle, with Isaiah Simmons and Jordan Hicks fitting the run in opposite directions. This forces Jalen Thompson to have to roll down and account for the running back.

I hate to make value judgments from where I sit, but the design of this run fit is begging to allow runs just like this, with nobody home to play the running back at the point of attack. Coach-speak — such as leverage, body positioning, alignment and assignment — can sound almost ethereal without the context of understanding intended outcomes, but this is where those terms come into play. A safety aligned outside of the box has to roll down into what’s effectively the A-gap long after the snap to fit the run.

Related content for you: How Lamar Jackson and the Baltimore Ravens' offense closed out a Week 2 win over the Kansas City Chiefs via Diante Lee

Safeties roll down into the box as part of the run fit all the time, and there’s value in it from the standpoint of disguise. However, if the defense is so committed to its disguise that it cannot leverage and fit the run without safeties and linebackers rapidly changing directions, the structure of the defense is unsound.

In the next clip, there’s no window dressing at all; it's a straightforward zone run. The Cardinals are, again, trying to rotate late to get the run-fitter it needs for the running back (you can see it in Isaiah Simmons moving quickly to get outside of the tight end — he’s the flat player and thus in run support).

Budda Baker is rolling down as a “hook” player, responsible for fitting the run in the box on the tight end side, so Jordan Hicks should be fitting the run to the open side of the formation and thus trailing behind the flow of the play in case of a cutback. However, he sprints to fit the gap in front of him, and when the ball cuts back, there’s nobody home (again).

Minnesota's slot receiver deserves the credit for the stop because that’s the only thing that kept this play from gaining far more yardage.

This was a recurring theme all game, with nobody home for the cutback. Again, jet motion brings the nickel over to play in run support and against the threat of the sweep. Also again, the linebackers flow hard with the run action instead of adjusting the run fit accordingly, and now Dalvin Cook can cut back away from the flow of the defense and get upfield with almost no resistance.

Fitting the run this way is untenable long term, and it will have to be fixed structurally before anyone can get solid footing on evaluating the quality of the Cardinals' individual defenders.

Like: The Carolina Panthers’ Mugged Pressure Package

| Saints Down & Distance | Success Rate |

| 1 | 2/17 (12%) |

| 2 | 2/13 (15%) |

| 3 | 2/11 (18%) |

For an offense like the New Orleans Saints‘ — specifically, a quarterback like Jameis Winston — the top goal is to stay on schedule and avoid obvious passing situations. But without Michael Thomas and going into Week 2 without half of the offensive coaching staff, offensive coordinator Pete Carmichael had his hands full.

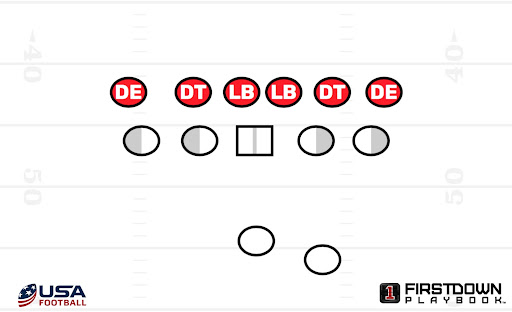

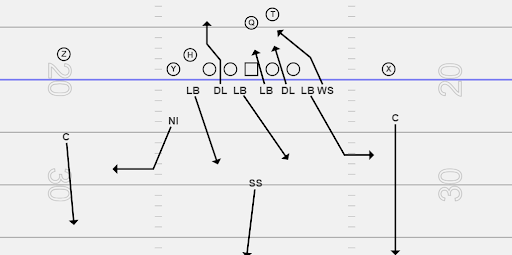

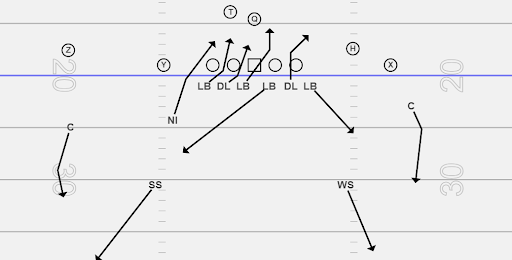

Panthers defensive coordinator Phil Snow was able to take full advantage. On 10 different occasions, Carolina presented what’s called a “mug” front, with four down linemen and two inside linebackers walked up into their gaps. Most often, the linebackers are in the A-gap to manipulate the center, who has to set the protection to slide a particular way so the running back knows which potential blitzer or pass-rusher he’s responsible for.

Because the defense has multiple options for who can rush and who can drop out into coverage, it’s imperative that the protection is set properly, and the quarterback knows where potential unblockable pressure can come from. New Orleans had repeated trouble against this look, and Carolina was able to manufacture free rushers on Winston throughout the game.

In the first mug look, Carolina brings three rushers on to the side of the back and drops two potential rushers out away from the back. Because New Orleans released Alvin Kamara instead of keeping him in to block, the protection would have to be set to the side of the back to get the center, guard and tackle to pick those three up.

Because it’s set opposite, the guard and tackle have to account for the two “most dangerous” players. The linebacker rushing the A-gap opposite of the center has to be accounted for by the guard, leaving left tackle Terron Armstead responsible for three potential rushers — a no-win situation. Winston was able to avoid the interior pressure, but this snap was an omen for what was to come.

The next clip is a similar look — but bringing four from the same side instead. One minor detail is a veteran move by safety Jeremy Chinn: the pressure track is meant for Chinn to press through one gap into another, to open airspace for defensive linemen to slant into the next gap inside. When he sees Kamara stepping up to pick him up, he gives himself up by running into the block and opens up an unblocked edge pressure for safety Sean Chandler.

Carolina runs this pressure track three times in a row to finish the half, and on the last snap, Kamara steps out to the edge and opens up unblocked pressure for Chinn this time. This leads to Winston’s end-of-half interception.

Phil Snow returned to the three-from-a-side pressure in the fourth quarter and generated unblocked pressure again. Armstead learns from the earlier rep and steps down to the B-gap, but with Kamara releasing again, there’s no one to pick up edge pressure. It leads to a sack.

The Saints missing their offensive line coach probably led to a lot of these issues going unfixed over the course of the game. However, because they can’t manufacture open wide receivers down the field at the moment, having to release Kamara into a route all the time opens the door to having the protection manipulated throughout the season.

© 2026 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2026 PFF - all rights reserved.