(Metrics that Matter is a regular offseason feature that examines some aspect of fantasy through a microscope to dive into the finer details.)

In our last article, we examined the fact that quarterbacks are much more efficient when operating from a clean pocket, rather than when throwing under pressure. Of course, this makes sense intuitively, but there’s another less-discussed factor quietly impacting quarterback efficiency — the frequency of play-action passes.

Over the past three seasons, quarterbacks average a 103.5 passer rating on play-action, but only 90.1 the rest of the time. Over this span, passers attempted a play-action fake on just 19.9 percent of their total passes.

Over the past three seasons, passer rating had a 0.14 positive correlation to play-action pass attempts in games. A quarterback’s play-action passer rating was slightly impacted by the frequency of rushing attempts within a game (a 0.14 correlation), while yards per carry had a negligible effect (-0.02). Even when teams ran an especially high number of play-action passes within games (10 or more), the results were the same (93.5 on non-play-action passes vs. 109.3 on play-action passes). Even when a team’s running back carried the ball an especially small amount of the time (fewer than 20 times in one game), we see the same result (85.0 vs. 97.4). And even when rushing efficiency is poor (a team yards per carry is below 3.5), again we see the same thing (93.0 vs. 108.4).

In 2016, New England led the league in play-action passer rating (131.6) on 207 play-action passes. In 2017, Bill Belichick responded by having Tom Brady attempt 151 play-action passes, the most by any quarterback over the past three seasons. Perhaps Belichick is already aware of this efficiency hack, but I’d suggest that all other teams start utilizing play-action at a higher rate, and especially so if you’re already a run-heavy team. I think this could be an effective means of gaining a small edge on the rest of the league.

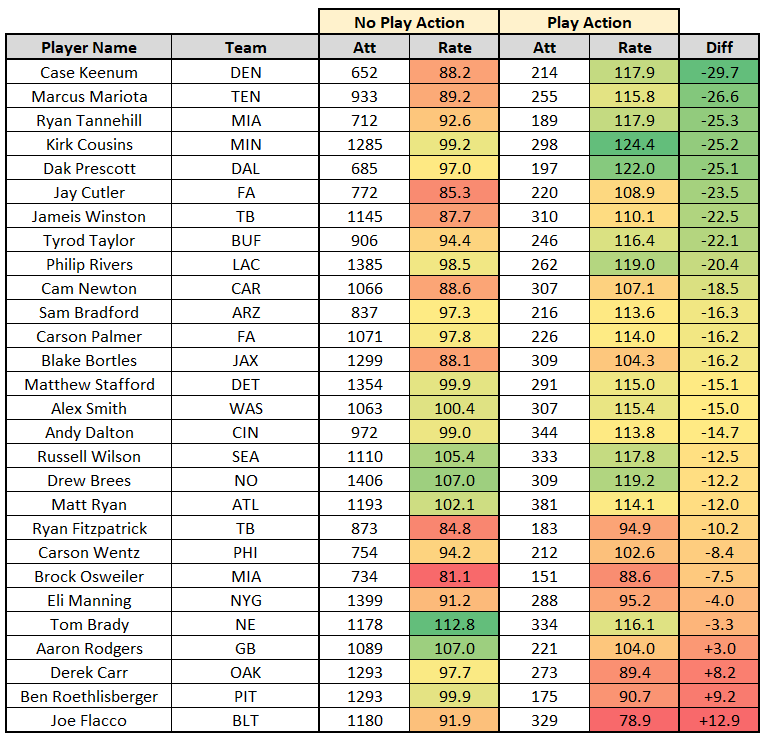

From a fantasy perspective, I suspect there might be utility here for us as well. Using our play-action data, available to Elite subscribers, I contrasted a quarterback’s efficiency on play-action vs. on non-play-action passes over the past three years. Here’s the chart (min. 850 pass attempts):

Who stood out?

Case Keenum – Keenum showed the largest discrepancy in play-action passer rating (117.9) vs. non-play-action passer rating (88.2). This could be a legitimate concern for him in Denver. Minnesota ranked second in play-action passes last season, while Denver ranked 11th. Denver has a new offensive coordinator in Bill Musgrave, but the Oakland Raiders in 2016 (Musgrave’s last season as an offensive coordinator) attempted even fewer (32 less) play-action passes than Denver did last season, with the seventh-fewest play-action attempts that year.

Marcus Mariota – Like Keenum, Mariota was much better on play-action passes, and he led the league in play-action passer rating last season (122.8). Again, like Keenum, he’ll be saddled with a new offense this year, under Matt LaFleur, who comes from the play-action-heavy Los Angeles Rams (third-most in 2017). I suspect he’ll bring over an offensive identity heavily influenced by Sean McVay, but it’s not a given LaFleur’s arrival means more play-action passes (Tennessee ranked 19th in play-action passes last year) for Mariota, considering we’ve never seen LaFleur call plays at the NFL level.

Kirk Cousins – Cousins leads all quarterbacks within our sample in play-action passer rating. Luckily for him, Minnesota ranked second among all teams in play-action pass attempts last year, and by 35 more than the Washington Redskins, who ranked 18th. Minnesota does have a new offensive coordinator this year (John DeFilippo), who may be less aggressive in calling play-action passes than Pat Shurmur. In DeFilippo’s last year as offensive coordinator (2015 with the Browns), his team ranked 24th in play-action passes. However, perhaps he opts for a more play-action-heavy approach next season to account for Cousins’ strengths. If this is the case Cousins might be in a better situation than he was in Washington. As we mentioned earlier, team rushing attempts has a positive correlation to play-action passer rating, and Minnesota ranked second in team rushing attempts last year, while Washington ranked 22nd.

Dak Prescott – Right behind Cousins, Prescott has the second-highest play-action passer rating within our sample. Perhaps this played a role in his dramatic fantasy splits during Ezekiel Elliott’s suspension. Last year, Prescott averaged 19.6 fantasy points per game when Elliott was on the field, but only 13.8 fantasy points per game in the six games Elliott was absent. For perspective, 19.6 fantasy points per game would have meant finishing fifth at the position, while 13.8 would have ranked 25th. Prescott also averaged 5.1 fantasy points per game (with a 133.3 passer rating) on play action passes when Elliott was on that field, with those numbers dropping to 1.9 fantasy points per game (and an 83.0 passer rating) during Elliott’s suspension weeks. Perhaps teams didn’t take the threat of play-action as seriously without Elliott on the field, and Prescott’s efficiency suffered as a result.

Aaron Rodgers, Derek Carr, Ben Roethlisberger, and Joe Flacco – On the other end of the spectrum we have four quarterbacks who actually posted a higher passer rating on non-play-action passes. This seemed weird to me, but perhaps the connection is all four passers’ teams also ranked bottom-10 in team rushing attempts over our sample. In the case of Roethlisberger, even if we bring the sample back to 2012 (when we first started recording play-action numbers for quarterbacks), Roethlisberger’s play-action passer rating was less than a full point higher than his non-play-action passer rating. Perhaps offensive coordinator Todd Haley (now with the Browns) was aware of this, considering only 11.9 percent of Roethlisberger’s pass attempts came on play action, which was the lowest rate within our sample. Similarly, Rodgers’ 16.9 percent play-action pass rate was the third-lowest within our sample.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.