The 2022 NFL Draft appears to be yet another draft overflowing with talent at the wide receiver position. While we are unlikely to see three wideouts drafted within the top 10 for the second year in a row, there are currently five wide receiver prospects ranked within PFF’s top 32 prospects, and 15 within the top 100. These prospects all come from vastly different offenses, were asked to do different things and played with quarterbacks of varying skill levels. So, how do we go about evaluating them with data?

Click here for more PFF tools:

Rankings & Projections | WR/CB Matchup Chart | NFL & NCAA Betting Dashboards | NFL Player Props Tool | NFL & NCAA Power Rankings

Best Bets Tool

Similar to what we’ve already done with the 2022 quarterback prospects, we can do this with K-means clustering. Glossing over the technical details, this process gives us the means by which we can group together similar players and thus learn about their strengths and weaknesses by comparison. For our purposes, we will be looking at the 243 FBS wide receivers who have been drafted since 2015 and prospects who are likely to be drafted in 2022 to try to answer two questions:

- What were the prospects asked to do?

- How did the prospects produce?

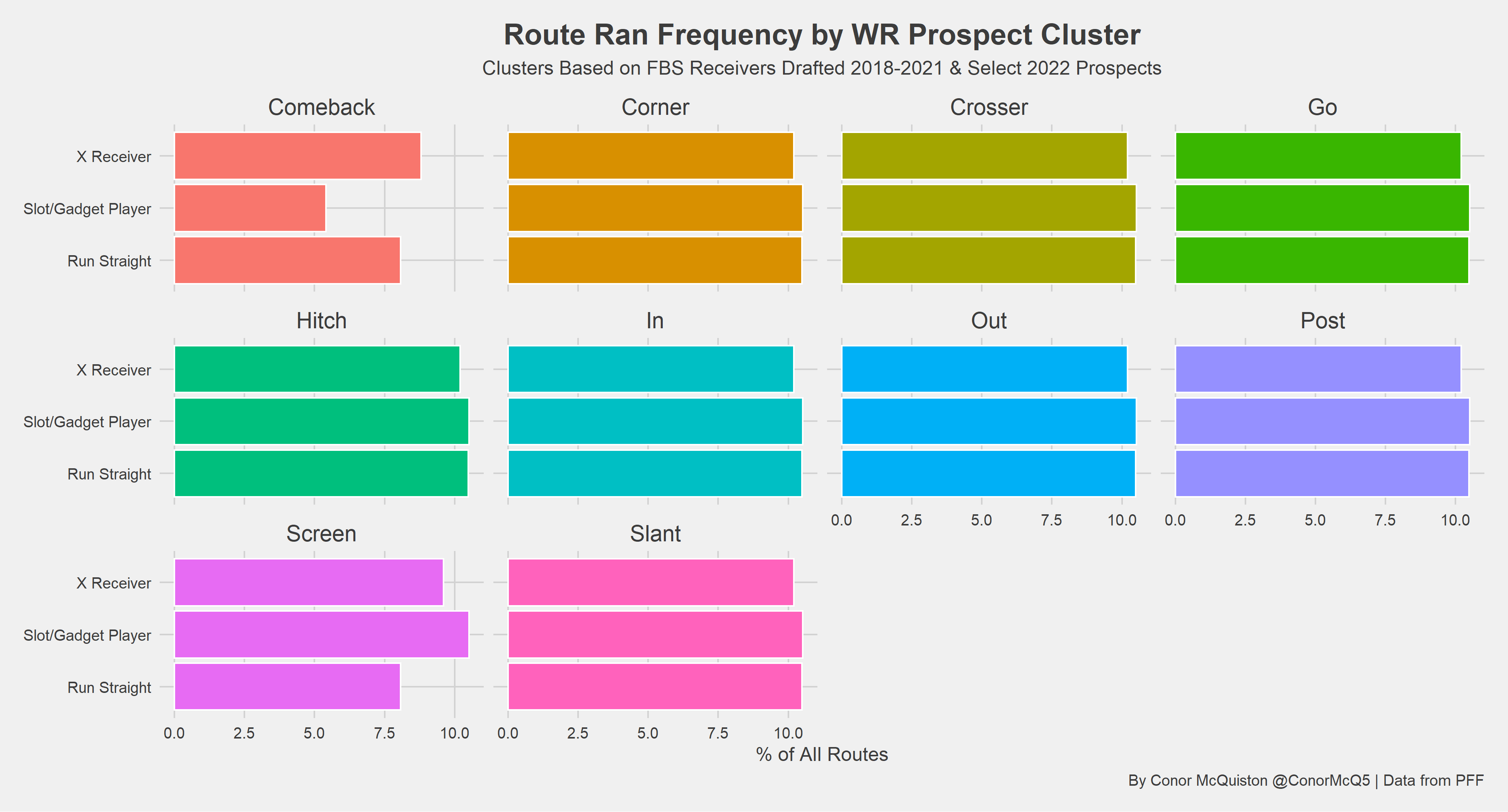

Our first question will be broken down into two subquestions: What did the offense want to do with the prospect structurally, and what routes did he run? We’ll start with the routes question, which unfortunately reduces our sample — PFF began charting non-targeted routes for college football only in 2018. We are left with 102 receivers, which is sizable but prevents us from comparing to older receivers. From this sample, we glean three major groups of route distributions:

The largest of the three groups is the X Receivers, with exactly half the sample fitting into this category. Wide receivers who are drafted are typically the most talented on their college roster, and thus tend to be slotted in as the primary passing option, the X Receiver. A useful example would be former LSU Tiger Ja’Marr Chase. From the perspective of route distribution, what these receivers are asked to do is fairly standardized across college football, so we’ll use it as a point of reference to understand the remaining groups.

Slot/Gadget Players are defined by their high screen rate and low comeback route rate. This indicates a higher volume of manufactured touches by the offense and the player rarely lining up as the No. 1 receiver to a side. Run Straight receivers are defined by exactly the opposite, with the opposite implications, and are typically height/weight/speed specimens best known for their downfield abilities. The prototypes of each group would likely be former Texas Longhorns Devin Duvernay and Collin Johnson, respectively.

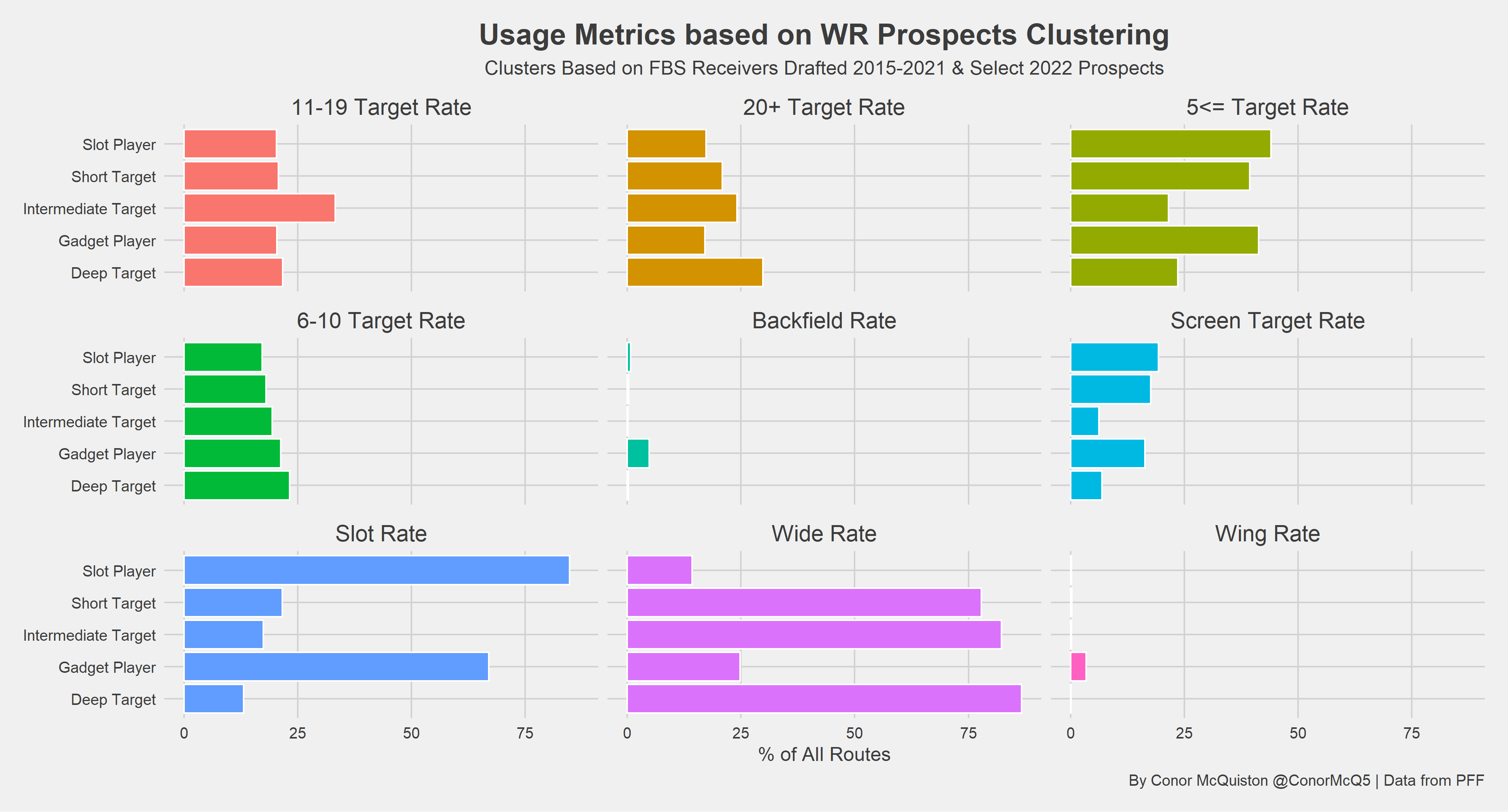

Given the relative homogeneity of route distributions, it is difficult to learn much from these clusters. But can we glean more if we take a macro look at where a receiver lined up and where they were targeted?

This allows us to recover five groups. Three of these groups lined up primarily out wide, while the remaining two primarily lined up in the slot. The wide groups are defined primarily by where they were targeted — close to the line of scrimmage, at an intermediate depth or deep down the field. We can build reasonable expectations for the abilities of each of these groups based on what their coaches asked them to do.

Particularly, we can expect that Short Targets create production after the catch, Intermediate Targets manage to separate by some means and Deep Targets win down the field in one-on-one coverage. These archetypes can best be understood via some examples, notably former South Carolina Gamecock Deebo Samuel for Short Targets, former Alabama wideout Calvin Ridley for Intermediate Targets and former Ole Miss Rebel D.K. Metcalf for Deep Targets.

Related content for you:

2022 NFL Mock Draft: Ole Miss QB Matt Corral lands in Washington at No. 9, Atlanta Falcons take Pittsburgh QB Kenny Pickett at No. 10

via Eric Eager

The differences between the Slot Players and Gadget Players are much more minute, mainly being whether the player lined up in the backfield as well as the slot. This may suggest that coaches have a lower expectation for gadget players to generate separation, but this is far from a certainty. We can reasonably expect, however, that these players were expected to create production after the catch. Useful examples are former Florida Gator Kadarius Toney for the Slot and former Ohio State Buckeye Curtis Samuel for the Gadget.

Now that we have a systemized way to make inferences from a player’s usage, we can go on to understand a player’s production.

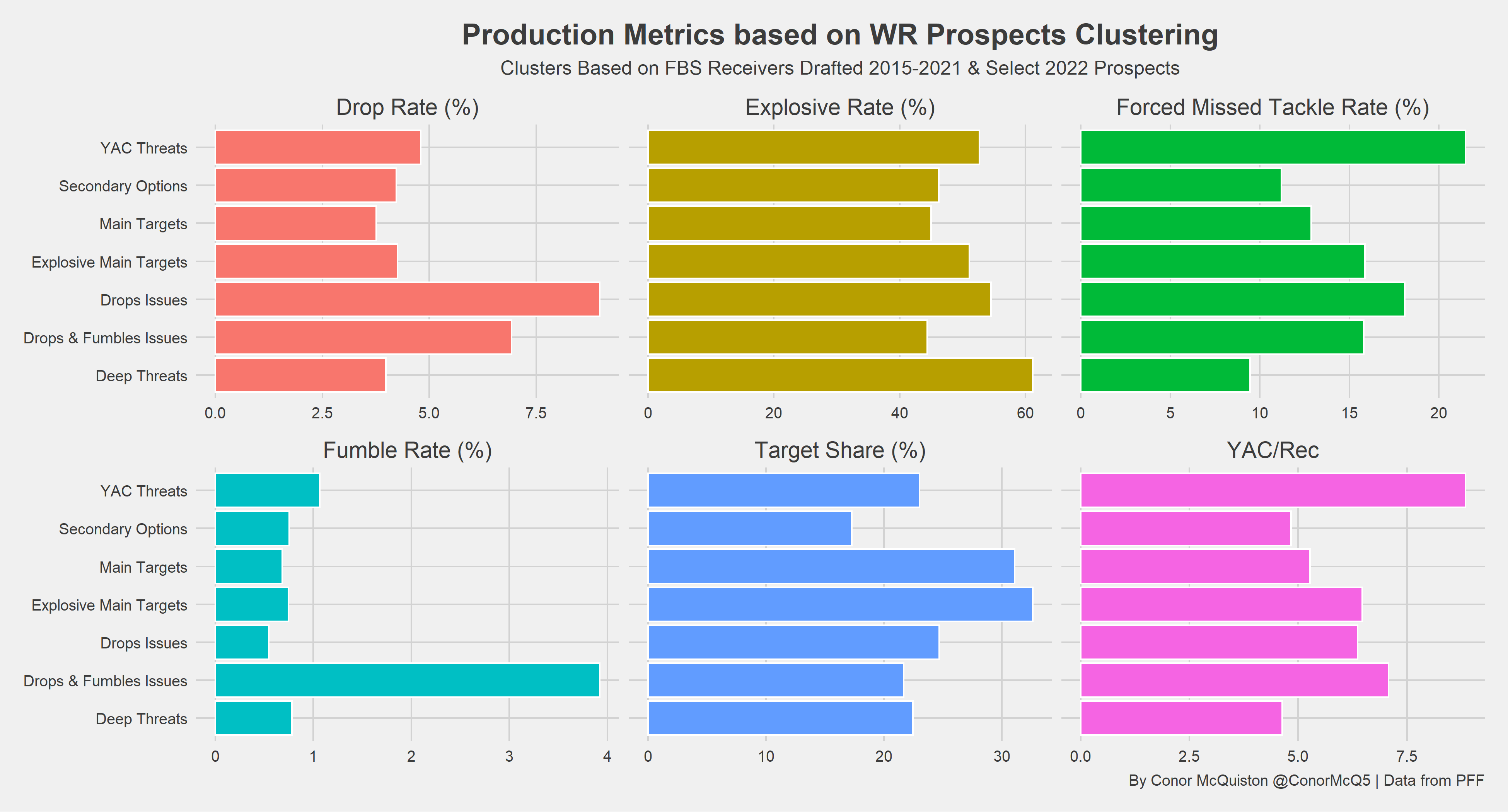

When looking strictly at production, we recover seven distinct groups. The two most self-explanatory groups are the YAC Threats and Deep Threats. Both have high explosive rates (note that we are defining explosive rates as passes that gain 12 or more yards), but the former achieves this by forcing missed tackles and yards after the catch (YAC), while the latter lags far behind in both metrics. This implies that the former wins after the catch, while the latter primarily wins before or during the catch, likely downfield. Former Arizona State Sun Devil Brandon Aiyuk is the prototypical YAC Threat, and former Georgia Bulldog Chris Conley is the same for the Deep Threats.

The Drops Issues and Drops & Fumbles Issues groups are similarly simple. Both have struggles holding onto the ball in one way or another, but the latter also tend to get more handoffs. The tradeoff that allows their teams to put up with this is they’re generally explosive and force more missed tackles in the process. The prototypical members of these groups are Corey Coleman and Jalen Reagor, which fails to inspire much confidence.

The Secondary Options, Main Targets and Explosive Main Targets are primarily defined by their target shares. Target share refers to the percentage of a team’s total targets that went to that receiver, and thus these groups require more film-based context comparatively. As the name suggests, the Secondary Options are united by having low target shares. This could indicate the players either benefited from attention being put toward the primary option, got hurt or carved out a niche role. One such example is former Clemson Tiger Hunter Renfrow.

Conversely, the Main Targets and Explosive Main Targets were their team’s primary weapons in the passing game, but the latter had more explosives. Given their higher YAC and forced missed tackles, it appears this is mostly the result of differences in ability after the catch. This becomes most evident when comparing Calvin Ridley, a Main Target, and fellow Crimson Tide alumnus DeVonta Smith, an Explosive Main Target.

Now that we’ve discussed the groups receiver prospects tend to find themselves in, we can apply this to the 2022 WR class and form better priors about their strengths and weaknesses.

| Player | Usage Cluster | Route Cluster | Production Cluster |

| Garrett Wilson | Short Target | X Receiver | YAC Threat |

| Jameson Williams | Intermediate Target | X Receiver | YAC Threat |

| Drake London | Short Target | Run Straight | Drops Issues |

| Chris Olave | Intermediate Target | X Receiver | Deep Threat |

| Treylon Burks | Gadget Player | Slot/Gadget Player | YAC Threat |

| Jahan Dotson | Short Target | X Receiver | Main Target |

| John Metchie III | Short Target | X Receiver | Explosive Main Target |

| Skyy Moore | Short Target | Slot/Gadget Player | Explosive Main Target |

| David Bell | Short Target | X Receiver | Main Target |

| Jalen Tolbert | Short Target | X Receiver | Explosive Main Target |

| Wan’Dale Robinson | Slot Player | Slot/Gadget Player | Main Target |

| Romeo Doubs | Short Target | X Receiver | Deep Threat |

| Justyn Ross | Short Target | Slot/Gadget Player | Secondary Option |

| Khalil Shakir | Slot Player | Slot/Gadget Player | Drops Issues |

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.