With free agency in full swing, the 2022 NFL season is upon us. However, when it comes to longevity’s sake, free agency is nothing more than a flicker in terms of time taken. A few big names come off of the board (or already have), some trades go down (or already have), season win totals get posted, and we’re on to the draft.

That’s what I want to talk about today: the draft. And specifically, I want to discuss a position that has not gotten really any love, which we are partially responsible for here at PFF: running back.

Click here for more PFF tools:

Draft Guide & Big Board | Mock Draft Simulator

Dynasty Rankings & Projections | Free Agent Rankings | 2022 QB Annual

Player Grades

The running back position in the NFL is starting to see its capital allocation match its on-field value. In some years, there are no running backs taken in the first round, and in most years (such as 2021), the one taken in Round 1 yields consternation (and a subsequent lack of team success). This is due to many factors, but one of them is that the running back production is significantly tied to the table set by the offensive line — no position is more tied to other players' performance than the players carrying the ball.

Luckily, PFF measures offensive line performance. This fall, I wrote an article that caused a pretty big stir in the football community, where I showed that early-down runs were affected to the tune of half of an expected point based on whether the play was perfected blocked (i.e. no one got a negative grade from PFF) or not perfected blocked (at least one player earned a negative grade from us). A perfectly-blocked run play on every single play for an entire season would give that offense an EPA that was at or near the league’s best mark. However, such plays only occur on roughly a third of all running plays, which is why running the ball is less efficient than passing on average.

As far as running back performance on these plays, I showed that running back performance on not-perfectly-blocked runs — while weaker than on perfectly-blocked runs — was more stable year-to-year than those when everyone executed their block.

Now, I want to take that analysis a step further to see how a running back's performance on those plays at the college level maps to performance at the NFL level.

PFF has been collecting college football data since 2014, and what is interesting is that the gap in team performance when a run is perfectly blocked versus not perfectly blocked is about the same (about 0.57 EPA difference on early downs) in college as it is in the NFL. Here are the highest performing running backs in the 2022 NFL Draft when a play is not perfectly blocked during their college careers:

Yards rushing and yards per carry rushing on not-perfectly-blocked runs (career)

| Player | Yards | Yards per carry |

| TJ Pledger | 662 | 4.90 |

| Rachaad White | 617 | 4.60 |

| Pierre Strong Jr. | 1624 | 4.57 |

| D’vonte Price | 938 | 4.45 |

| Kenneth Walker III | 1366 | 4.42 |

| Tyler Allgeier | 1156 | 4.38 |

| Abram Smith | 771 | 4.26 |

| ZaQuandre White | 268 | 4.25 |

| Kennedy Brooks | 987 | 4.20 |

| Breece Hall | 1873 | 4.20 |

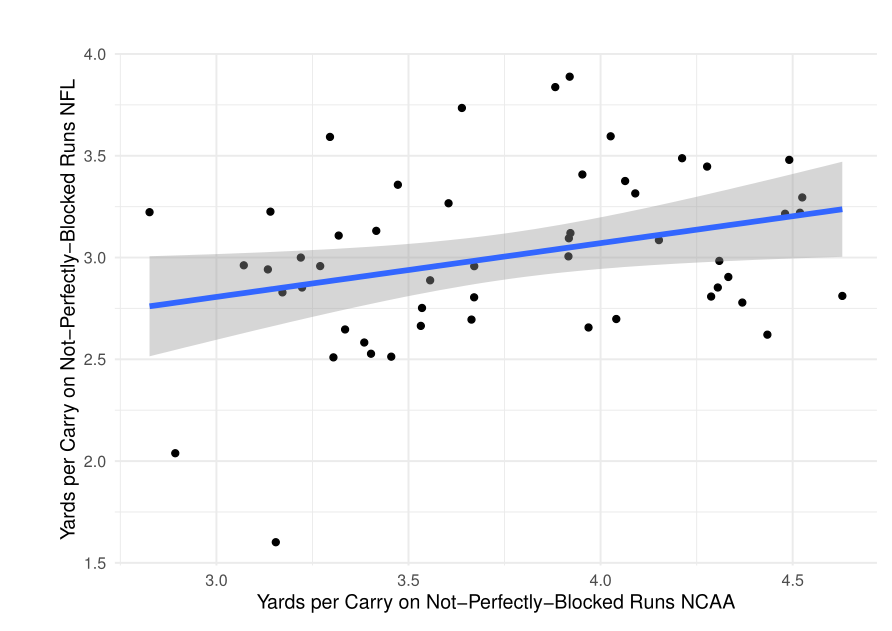

Some truly impressive feats here, as Pledger averaged almost five yards per carry when someone misses their block. The top back on PFF's big board, Walker, earned a solid 4.42 yards per carry when the play wasn't perfectly blocked for two schools. The correlation between yards per carry on not-perfectly-blocked runs from college to pro was a reasonable r = 0.31, which is lower than overall (r = 0.43) for players who had 150 carries at the college level that weren’t perfectly blocked and 75 carries at the pro level (n = 52):

Correlations for expected points added were about the same. Notice in the plot above that while there are a decent amount of running backs who can earn more than four yards per carry when a play isn’t blocked well, that feat at the NFL level is basically reserved for guys such as Nick Chubb, and not for a whole season. The NFL is just a much harder game to win individually with physical feats like that. Here is the list for perfectly-blocked runs:

Yards rushing and yards per carry rushing on perfectly-blocked runs (career)

| Player | Yards | Yards per carry |

| Jerome Ford | 1079 | 11.10 |

| Pierre Strong Jr. | 2901 | 10.70 |

| Kennedy Brooks | 2334 | 9.93 |

| Abram Smith | 873 | 9.81 |

| Isaiah Spiller | 1610 | 9.58 |

| Tyler Allgeier | 1772 | 9.53 |

| James Cook | 1059 | 9.21 |

| ZaQuandre White | 344 | 9.05 |

| Rachaad White | 791 | 8.99 |

| Tyler Goodson | 1392 | 8.92 |

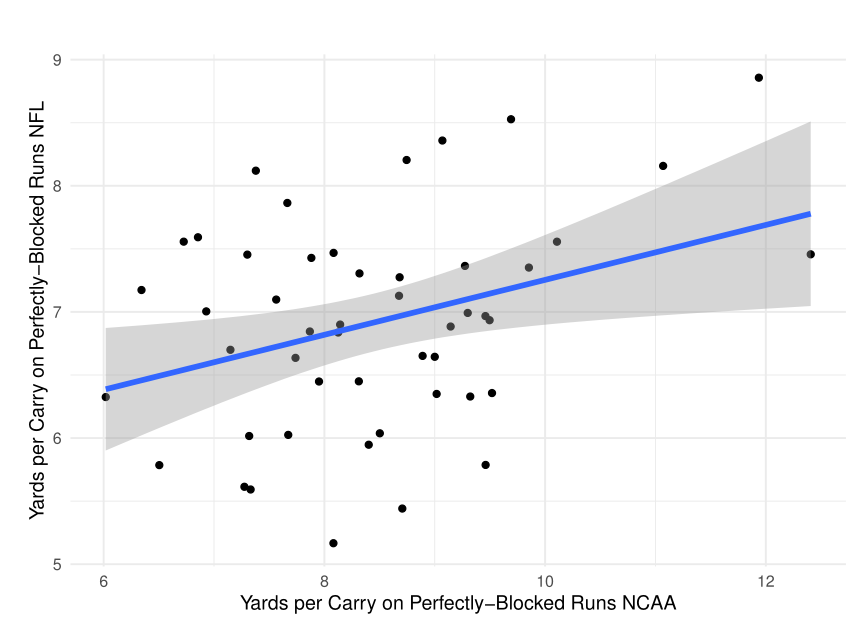

Some repeats from the previous list like South Dakota State’s Strong, Oklahoma’s Brooks, Baylor’s Smith and BYU’s Allgeier near the top of the list. Cincinnati's Ford was a big reason the Bearcats made it to the College Football Playoff due to the litany of explosive plays he created. Interestingly, we actually find a higher correlation between how a player does on these perfectly-blocked plays from college to pro than not-perfectly-blocked runs (r = 0.34).

Again, this correlation is not as high as it is for yards per carry in general, but breaking a player’s performance into these two buckets is very instructive in terms of finding a “type” in the draft. For example, while Walker is an excellent running back when the play breaks down, he did not show the ability to break off long runs the way that Ford did when everything went right. Thus, if a team that has a poor offensive line might prefer Walker. A ready-made offense that's looking for a late-round running back to offer explosive plays might target Ford or Georgia’s Cook.

As we go through our college-to-pro series, we can toggle the expectations for players to the teams where they will be or are projected to be drafted, and adjust our rankings accordingly. Stay tuned!

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.