Betting a spread expresses a view that the market is incorrectly valuing the relative strength of two teams. This is true whether a bet is placed on the first-half spread or the full-game spread, and because sportsbooks do not price first-half and full-game spreads equally, bettors can optimize their bets by selectively wagering on first-half spreads when full-game spreads land on key numbers.

Subscribe to

First-half spreads and full-game spreads are highly correlated — if a team is favored for the full game, they will be favored in the first half, as well.

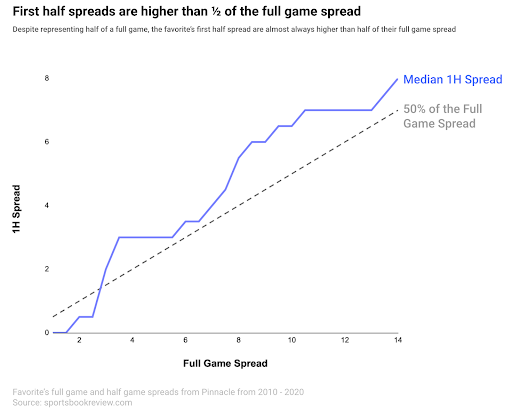

However, first-half spreads rarely equal half of the full-game spread despite representing exactly half the game. In fact, the first half spread is almost always more than 50% of the full game spread:

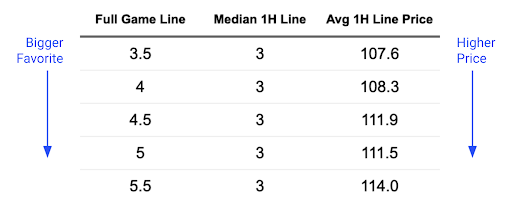

Just as full-game spreads gravitate toward key numbers, so too do first-half spreads. A team favored by 5.5 over a full game will, on average, have the same first-half spread as a team favored by just 3.5 over the full game.

Sportsbooks account for this key-number stickiness by charging less for teams whose first-half spread gravitates up to a key number:

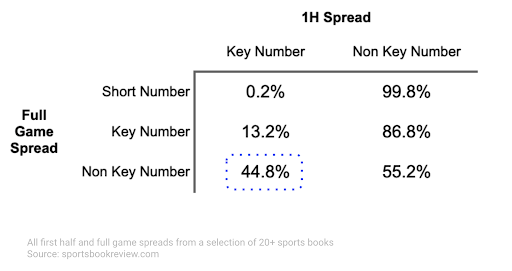

The necessity of any spread to gravitate toward a key number also impacts the frequency at which first-half spreads land on key numbers.

When a team is a short full-game favorite (PK to -2.5) or their full-game line lands on a key number (3, 7, 10, etc.), their first-half spread is significantly less likely to also fall on a key number:

A short favorite can’t be favored by more in the first half than they are over the full game, and a team favored by 7 over a full game would be too expensive to offer at 3 for the first half.

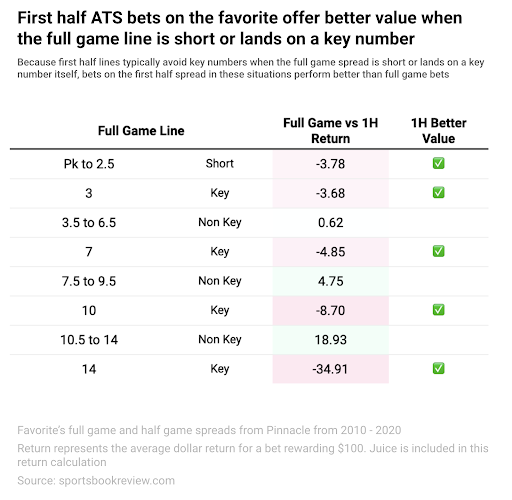

When the returns of first-half bets and full-game bets are compared, a pattern emerges:

When a team’s first-half number is pushed to a key number, the team is either being asked to cover a number too high (e.g., a -3.5-point full-game team covering a 3-point first-half spread) or the bettor is being asked to pay too high a price (e.g., paying $114 for a -5.5-point full-game team to cover a 3-point first-half spread).

As a result, first-half spreads tend to represent worse value when they land on a key number, which itself tends to happen more often when the full game spread is not a key number.

Blindly betting first-half and full-game favorite spreads based on whether the full-game spread was short or a key number yields a better return than blindly betting first halves or full-game spreads alone:

Now, betting anything blindly is unlikely to yield a positive return, but this insight can be used to optimize betting strategy when a bettor finds a team they’d like to back. If that team’s full-game spread is being pushed to a key number, the bettor may be better off looking for a well-priced first-half spread that, instead, doesn’t fall on a key number.

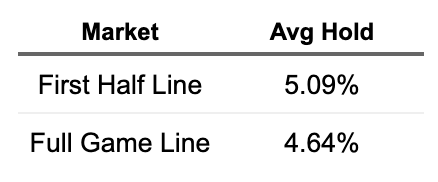

The operative phrase here is “well-priced.” Because first halves are harder to price and are a thinner market, they present more risk to books. As a result, books do take a higher hold on first-half spreads:

By selectively betting first-half spreads and shopping books to find the best price, bettors can find better value than betting full-game spreads alone.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.